I could predict the hour when I would receive the call. Cameron consistently demonstrated destructive behaviors during writing time—nudging a pencil off his desk, tearing down anchor charts. His teacher was frustrated. As the school principal, so was I.

After countless classroom removals, I suggested he not write until we figured out what was happening. “Not write?” the teacher asked, one eyebrow arched.

“It’s temporary,” I responded. “We can’t have him destroying your room every day.”

Systems vs. People

In these types of situations, it is easy to place the burden of responsibility on the student, the student’s family, or the teacher. As I walked back from the classroom to my office, my mind rattled with complaints. Why won’t Cameron just write? Is something happening at home? And why can’t the teacher figure out how to reach him? Later, I recognized these thoughts as projections of my own frustration and sense of failure. My suggestion that a student should not receive grade-level writing instruction was an attempt to control a situation beyond my singular influence. Without a clear understanding of the broader conditions for learning in our schools, we end up serving our institutions over our students and even our teachers.

This article makes the case that schools can be more intentional about interrogating the practices and policies that may be contributing to some of the very problems we attempt to prevent in the first place. Put more succinctly, I advocate for being hard on the systems and gentle with the people. This means holding policies and practices accountable (vs. individuals) for the teaching and learning conditions. This means ensuring that teachers and students receive the flexibility, support, and understanding they need to succeed. This means leaders being transparent about the current constraints within the organization while empowering all staff as decision-makers to do the best they can within their current reality.

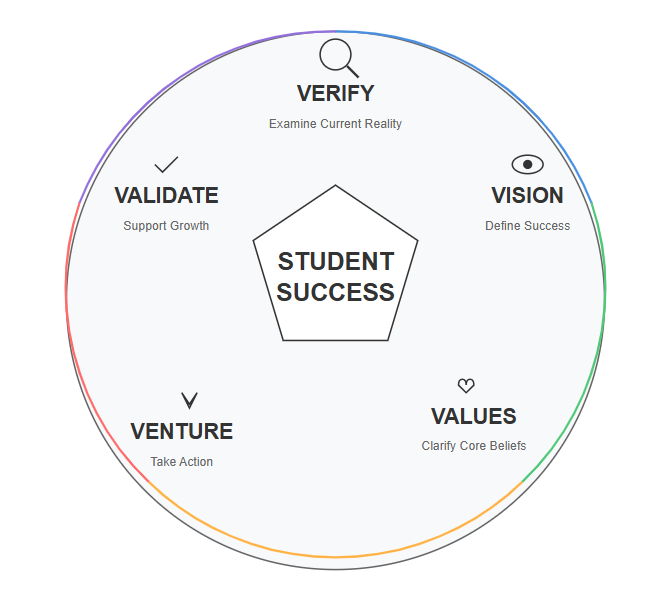

Five Entry Points for Fixing Systems, Not People

The following five entry points help leaders examine systems that may be creating barriers for teachers and students. I refer to it as the Five Vs, which have surfaced organically over the two years I have served as a systems coach.

There is no one right place to start; initial coaching conversations with key educators involved will reveal where to begin. If the entry point is unclear, begin at verifying current reality and creating a vision for success. These two areas tend to directly address the challenges students and teachers are experiencing.

Verify Current Reality

Key question: What’s working, what isn’t, and how do we know?

Jessica, a special education teacher in a secondary school, wanted to scale up inclusionary practices across the organization. Specifically, she advocated for co-planning and co-teaching. “The way my students describe their experiences, especially of not feeling singled out for their disability, really motivates me to want to give all of our students access to this approach.”

Define a Vision for Success

Key question: If we could wave a magic wand, what would we want to see and experience?

I asked Jessica, “In the ideal classroom, what does co-teaching look like and feel like?” This “magic wand” question helps people envision possibilities. Jessica listed key features, including students seeking help from either teacher without labels.

Clarify Your Core Beliefs and Values

Key question: Where do our values align with our vision, and where don’t they?

Jessica and I developed core beliefs that aligned with both the vision for co-teaching and the research that supports it. “All students can learn at high levels” and similar statements would be presented to the faculty. They would be asked to anonymously agree or disagree with each one while presenting about co-teaching to the staff.

Venture Out and Take Action

Key question: What can we do today to move this project forward?

In Jessica’s case, I offered the idea of engaging in an environmental walk. It’s a tool where educators examine evidence of school values by observing hallways, classrooms, and student work. Questions such as “How do these writing pieces demonstrate student understanding compared with the standard?” can be helpful in guiding participants to think more objectively.

Validate Effort and Growth

Key question: How do we know we are getting better?

We collected evidence across the school, such as student work on the walls, culturally inclusive signage, and how classrooms were set up for learning. Then we came back to Jessica’s classroom and summarized our findings. For example, we found that approximately 50 percent of teachers had set up collaborative student learning spaces, while the other half still stuck with rows. “What does that tell us about the shared beliefs and values of this school?”

Jessica responded, “I think it says that we don’t have a common understanding about what best instruction really is.” We compared this finding with the shared belief that “All students can learn at high levels.”

“I think you can tell a powerful story about the current learning conditions and make a case for new teaching approaches,” I observed. Jessica agreed.

Some questions to consider journaling around:

- What challenges in the past have proved to be beyond your sphere of control or influence? What system barriers were likely in the way of success?

- If you could pick one person within your organization or connected externally, whom would you invite to help conduct an environmental walk and examine your systems?