Last week Tammy joined a kindergarten teacher, Vicki Haley, for her writer’s workshop. As we all know, the reality of kindergarten is that even with the best-laid plans we can get off schedule. When Tammy first arrived, Vicki apologized that she was a bit behind, and shared that her students were getting ready for show and tell. We had planned to focus our time on strategies for generating important topics for personal narrative stories in writer’s workshop. The level of excitement was too high to change direction, so we went with show and tell.

Two sentences into the first show and tell, and we both knew that this was our opportunity for teaching. Vicki began to model how important objects can inspire personal narrative stories. The students had carefully chosen an object they wanted to share with their classmates. They told the story of this object, and why it was important during show and tell — these were perfect ideas for personal narratives. The three-dimensional object to hold and show helped the students add detail and voice to their stories. It was ideal — their favorite part of the curriculum became a springboard for better narratives in the literacy program. Here are some strategies we tried for using objects from show and tell as seed ideas for personal narratives.

Acting Out the Story of Your Object

At first, students just told about their object — what it was, why they brought it, or where they got it. We wanted to get to the story of their object, so we began by having kids act out the story of their object step by step. It might sound a bit like this:

Teacher: So tell us what happened first. How did the story go?

Student: Well I found this shell.

Teacher: Show us how you found it. Can you act it out?

Student: I was walking on the beach. We were playing in the water. Then I stepped on something.

Teacher: So you were walking down the beach and playing in the water — who were you with?

Student: My dad and my brother.

Teacher: Oh, so let’s add that. You were walking down the beach and playing in the water with your brother and dad. While you were playing you stepped on something. Then what happened? What did you do once you stepped on it?

Student: It hurt. So I looked down and saw this shell.

Teacher: What did you say? If you had a speech bubble in your story, what would be in your speech bubble?

Student: Ouch!

Teacher: So after you said “ouch!” and saw the shell what did you do next?

Student: I picked up the shell.

Teacher: Show us how you did it.

Student: [Bends down and picks up the shell and looks at it.]

Teacher: So you bent down and carefully picked up the shell to get a closer look. What happened next?

Student: I showed my dad and my brother. I asked if I could take it home and my dad said yes.

Teacher: He said “yes.” How did you feel when you heard you could take this shell home? What were you thinking?

Student: I was really happy. I do not have any shells at home. I wanted to have a shell for me.

Teacher: So today during writer’s workshop, you could write the story of your object. Is that a story you would like to write about?

Student: Yes.

Many young students might only retell their stories at this level of detail verbally, and with lots of scaffolding. Although their written product does not always reflect the oral story, we know that developmentally this oral rendition is the first step to understanding the craft of adding details and voice to your writing. Acting out the stories helps them to remember and articulate what happened in their stories.

Once they act it out, we scaffold their language to describe what they were doing in words. The next step was for them to translate these oral stories into illustrations during writer’s workshop. Then they begin to label their illustrations and add short sentences to express their story in words. This strategy definitely moved students from telling about something to telling the story of something. This learning could apply to any personal narrative writing they do throughout the years.

Using Dialogue to Tell the Story of Your Object

We know that dialogue is a great way to bring readers into the moments of stories. This is often a difficult craft technique to teach young children. In the example above, you can see how we encouraged the student to act out what he said in the moment. Once the student gives us the dialogue, we invite him to try this in his writing with speech bubbles.

We quickly draw the scene, and ask the student to touch the picture and tell us what he said. We then model how to draw a speech bubble and add the dialogue to the story. Again, it was much easier for the student to think about dialogue when he was acting out the story of his object. When he pretended to play in the water and then step on the shell, it seemed natural to say “ouch!”

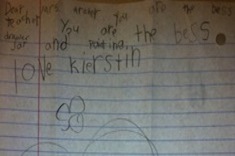

Speech bubbles are an accessible way for our youngest writers to bring their readers into the scene. Young children can write speech bubbles without writing full sentences. We find once one child tries it, it takes off and spreads throughout the room like wildfire.

Telling the Internal Story of Your Object

We often receive blank stares when we ask students how they were feeling in their story, or why their story is meaningful to them. This seems to be abstract in the context of writing a story, but it is crystal clear in the context of choosing an object to bring in for show and tell. Kindergarten students know the ritual of show and tell. They know the types of stories their classmates like to hear. Show and tell has authentic purpose. Students have to go through a process to select an object to share. The process of selection brings them to an understanding of why it is meaningful, and typically anything worth bringing in has some type of emotion tied to it.

In the example above, we scaffold the student by asking him how he was feeling, or what he was thinking at this turning point of his story. By isolating this moment of his story, we are modeling how writers stretch out the most important moment of their story and tell how they were feeling and what they were thinking. This adds voice and description. Again, many students enter this work orally, and then move to adding these craft techniques in later years. The process of adding feelings and thoughts to one’s writing is the same when it is done verbally, through pictures, or through writing. In kindergarten we want to begin with understanding how writers add thoughts and feelings to their writing even if students cannot produce them in writing yet.

Writer’s workshop in kindergarten is always a joy. This day was particularly joyous because we were reminded that developmentally appropriate practice, like show and tell, can also be rigorous and standards-based.