Certainly there are just too many words of positive advice for how to raise empowered students. Sure, of course, some people want kids who are inquisitive and energized to learn. Perhaps some people want to develop students who can dig deep into nonfiction books and see them as a window to discovery. I suppose some people would like to have the younger generation take over our world with the strength to communicate new ideas to others and do so with power, voice, and grace.

But what about the rest of us? What about those of us that want students who plagiarize everything, roll their eyes at the thought of researching anything, and spend more time on the glitter and graphics of their poster board projects than the actual content? It is time to take a stand for those of us that want to raise students who hate research. This, my brethren, is a list for you:

13 Ways to Raise a Student Who Hates Research

- Assume research is hard. Or boring. Or both.

- “Do research” only once a year, for eight weeks.

- Always assign topics to students, and offer no choice.

- Assign books to students and/or a strict requirement. (“Three books. Two articles. One Internet site.”)

- Notecards. Yes.

- Give out graphic organizers that provide fill-in-the-blank templates for every step of their process. (“The state bird is __________. It looks like __________.”)

- When students copy directly out of books they are reading, assume it is developmental.

- If you do wish to improve notetaking, repeat to students: “Put it in your own words.”

- As an alternative to point 8, teach students a complex way of taking notes that you would never do yourself.

- Make sure students believe that writing about their research is a way to prove they followed your assignment and read the required material.

- Because research is hard/boring (see point 1), accept that students research writing will lack voice and passion.

- Provide little time in school for reading or writing. Feedback is only necessary when they turn in “drafts.”

- Be their only audience. Have students end their research process by turning their work in only to you.

What Those “Research Lovers” Do

Now, I hate to bring this up, but if we are going to hold fast to leading students to hate research, then we should probably know what those “research lovers” do to inspire the children in their lives. You know, to avoid it.

For instance, research lovers usually make research an everyday activity, not just one long project. Stephanie Harvey and Harvey Daniels refer to this idea as “micro-projects” in Comprehension and Collaboration: Inquiry Circles in Action. They suggest that you take small moments out of your day to be curious by inviting students to ask questions, imagining how they might answer them, even inviting them to run to a computer or plan to ask someone at home. Even the Common Core State Standards encourage students to engage in short studies, not just long ones. Writing Standard 7 is directly at odds with the drawn-out once-a-year-only project.

Inspirational research teaching, if you are into that sort of thing, probably also includes you — as the educator — studying how you actually do research. What do you do when you look up dinner recipes, find a place to vacation, figure out why your child has a fever? Invite students into the process that all researchers go through and understand that it is often messy and broad at the beginning. Authors of the revised edition of Kate L. Turbian’s A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations, often considered the gold standard for research, agrees that there is no one way to begin a research process: “Researchers begin projects in different ways. Many experienced ones begin with a question that others in their field want to answer: What caused the extinction of most large North American mammals? Others begin with just a vague intellectual itch they have to scratch.”

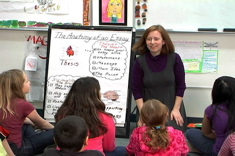

To help students become independent researchers who enjoy the process while developing new ideas, you could teach them ways of taking notes that are useful, not painful. In my book Energize Research Reading and Writing, I suggest ways to teach students to take notes on their learning, not directly from the book they are reading. For example, one simple step of covering up or closing a book before you take notes changes everything. I was just in a classroom where a student was taking notes on a book about lions. He was doing everything he could to paraphrase, which looked more like he was a walking thesaurus finding word by word synonyms. I asked him to read a whole section without jotting. “Read and just focus on really picturing what you are reading. Your job right now is to have new ideas about lions not memorize the words.” When he finished I said, “Now, put your hand over this page, don’t look at it. Think instead, ‘what did I just learn about this topic’ and take notes on your thinking.” He was amazing. He pulled out the big ideas of the passage and even spoke a bit about what interested him the most. Those became his notes.

Finally, if you want to develop students who loathe research, not love it, you would certainly never help them see how writing about research is really a form of teaching. Some classrooms study ways that researchers teach others, for example how PBS and Animal Planet use anecdotes to teach. In Laura’s fourth-grade class, her student wrote:

“It is a cold evening and the sun is about to set. The barn owl swoops down and finds the food in the meadow below. It likes to eat rats, rabbits, and birds.”

To see the Twitter conversation click here.

I mean, fourth graders. They are clearly too young to do effective and compelling research. That’s high school stuff. Right?

If you work hard enough you too can raise a student who hates research. I suppose if you worked differently you could also teach them to love it and learn to be empowered, energized, and inquisitive citizens. But who wants that?