My department was trying to fill a position in science education and we were interviewing a candidate who had worked extensively with inner-city youth to support their interest in and confidence about science. The job candidate presented a fascinating Powerpoint presentation showing photographs of the summer workshops she facilitated in which girls and boys from economically disadvantaged homes gathered for six weeks in the summer to explore science.

To measure the impact of the summer program on children's perceptions of what it meant to be a scientist, the facilitators asked students to take the Draw a Scientist Test (DAST) at the beginning and the end of their summer experience. The DAST was designed "as an open-ended projective test to detect children's perceptions of scientists" (Nuno, 1998) by asking them to draw a picture of a scientist doing science. Other researchers used Chambers' data to develop a checklist of children's stereotypes about scientists (i.e. Scientists are men in lab coats with crazy white hair presiding over bubbling flasks). Using this checklist, researchers have explored the connection between students' perceptions of what it means to "do science" and how their beliefs are affected by age, gender, geographic location, and instructional approaches.

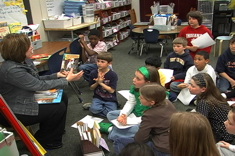

The uses of the DAST to explore possible influences on students' images of scientists suggested the potential of a modified version, what I called the Draw a Reader Test (DART), to explore children's beliefs about what it means to be a reader. When I floated this idea to a group of third grade teachers with whom I work, they were intrigued. Their district, in accordance with Reading First guidelines, had recently purchased a basal reading series for students in grades K-5, and teachers were expected to fully implement the program after a week-long summer training. Many of the teachers in my study group were concerned that the Harcourt program was focused too much on the quantitative gains students made in reading, rather than encouraging students to enjoy reading for its qualitative pleasures. Two teachers had just read Nancie Atwell's (2007) The Reading Zone and they saw the basal reading program as the complete antithesis of Atwell's reading workshop approach. Targeting the disconnect between teachers' beliefs about effective reading instruction and the reading curriculum mandated by their school, I suggested that we try the DART with third graders to see what we discovered.

With the help of preservice teachers working in a professional development partnership at the local school, we devoted five thirty-minute sessions to collect DART data. Third graders were asked to "draw a picture of a reader reading" on one side of a piece of paper. On the other side, we asked them to write a brief explanation of their drawings, and to indicate their name, age and gender. In total, drawings and explanations from sixty-two students in four third-grade classrooms were collected and analyzed. You can download a copy of the template we used for the test by clicking here.

Data and Expectations

Before diving into an analysis of the DART, my study group talked about what we expected to find. We imagined we would see pictures of students at desks, hovering dutifully over textbook-like tomes, perhaps filling out worksheets. One teacher said she expected to see drawings of readers with no books in front of them; instead, "readers" would be writing answers to the all-too-frequent chapter assessments. Another teacher anticipated seeing the classic school scene with a teacher at the front of the room, writing on the blackboard, with students watching her work. Again, no real reading in sight.

We reached consensus in our prediction that the DART, as an assessment tool, would reveal students' limited descriptions of "doing" reading, thus confirming teachers' beliefs that using a basal series undermined reading instruction.

Defying our certainty about what we expected to find, the emerging patterns in our DART data surprised us. Rather than pictures of students bent over basal at their school desks, the majority of third graders in our sample drew readers outside of school relaxing in their bedrooms, outdoors, or in libraries. One student drew a picture of a boy reading while riding on a skateboard that was headed directly toward a tank filled with sharks. On the back of his drawing, the student wrote, "Sometimes when you read, you don't pay attention to where you're going!" Of the sixty-two drawings we examined, only six showed readers reading in school. (One was a picture of a student in the library looking up a word in the dictionary, another showed a student with a thought bubble over her head that said, "I wonder what I can talk about in book group today?" The other four drawings showed readers in small discussion groups tucked in the corners of their classroom.)

We were particularly surprised by the lack of a school context in students' DART drawings. We predicted that having a teacher ask students to complete the DART during class time would automatically bias kids' selection of setting. Our examination of the data suggests that the context of the assessment was not an influence. We puzzled over this "out of school" pattern for a while, until one teacher said, "I get it! They have two different definitions of what reading is. There's school reading and real reading. Most kids drew pictures of real reading — on their beds at home, leaning against a tree in the park, snuggled next to mom on the couch. They don't think what they do in school is "real" reading; it's something completely different." My study group liked this interpretation and began strategizing about ways we could follow up the DART to dig deeper into students' perceptions of what reading is — and isn't.

Next Steps

As our study group inquiry continues, high on our list of next steps are the following ideas:

1. Develop a think aloud protocol to test our theory about students' definitions of real reading versus school reading. After completing the DART, some probing questions might include, "Why did you choose this setting for your illustration?" or "How did you decide where to put the reader in your picture?" If the setting of the original picture was out of school, we might ask, "If you had decided to draw your reader in school, what would the setting look like? What would your reader be reading?"

2. With subsequent classes of students, have one group complete the DART in class and another group complete it at home. As one teacher pointed out, "With two contexts, we can look at whether where you do the DART influences how you characterize a reader."

3. Try the DART with younger students and older students to compare and contrast emerging patterns.

4. Finally, we feel obligated to ask the "so what?" question. As an assessment tool, what does the DART yield that might help us support our students' reading development? What can we learn from students' drawings that could influence the direction of our instruction?

No one liked this "so what?" question because we were all intrigued by the unusual approach ("Finally", one teacher commented, "a way for students to share their thinking that doesn't involve writing paragraphs of self-reflection") and by the initial results. But as reflective practitioners, we are duty-bound to identify relevance.

The answers to "so what?" are still surfacing. One study group member wondered, "What if we just present the data and our idea about school reading vs. real reading at a faculty meeting, then open it up for discussion? At least this would move the conversation about using the basal reader forward." Another teacher said, "If looking at these data helps reassure me that what we're being asked to do with the basal reader isn't overshadowing other parts of my reading instruction — like SSR, discussion groups, read aloud and home reading — then I can live with the decision to bring this program to our school. The DART doesn't have to be any more rigorous than that."

From my perspective, the DART is valuable for several reasons. First, the decision to use it was spurred by teachers' discomfort with teaching practices that didn't square with their professional beliefs about reading instruction. Identifying that tension and finding a way to explore it in a systematic way is the heart of teacher research, a process I believe is the best way to support what Hord (1997b) calls "professional learning".

Second, the DART has the potential to broaden our definition of reading by soliciting students' perceptions of what it means to be a reader. People use reading for many purposes; our newest readers are just beginning to see the potential of reading in multiple contexts for multiple reasons. By asking young students to draw pictures of readers reading, we are given a window into the many ways reading is "working" in their lives. With this information, we see what they already know, and we identify the places that still need to be revealed through our instruction. Carol Ann Tomlinson, in an article calledLearning to Love Assessment (2007-2008) reminds us that,

- Informative assessment isn't an end in itself . . . the greatest power of assessment information lies in its capacity to help me see how to be a better teacher. If I know what students are and are not grasping at a given moment in a sequence of study, I know how to plan our time better. I know when to reteach, when to move ahead, and when to explain or demonstrate something in another way. Informative assessment is not an end in itself, but the beginning of better instruction (p. 9).

Finally, the Draw a Reader Test accomplishes many of the objectives of the Draw a Scientist Test. The DAST was designed to explore students' perceptions of scientists before and after a high-quality experience in the teaching and learning of science. Researchers were able to use the DAST data to identify gaps in students' understanding of what it meant to do science and then to address those gaps through instruction. A post-DAST gave researchers more information about the effect of the intervention on students' perceptions of what it meant to do science.

Changes Over Time

The science educator I referred to earlier in this article showed before and after illustrations from the children who participated in her summer science program. The differences were astonishing. Illustrations before the summer science enrichment were filled with those Einstein look-alikes installed in classic science laboratories complete with Bunsen burners and hen-scratched blackboards. Drawings after the summer session were unrecognizable when compared to their predecessors. Illustrations depicted scientists of both genders, multiple ages, and many nationalities. One picture showed a woman knee deep in the Red Sea studying marine life. Another showed a young African American boy on top of Mt. Everest laden with meteorological equipment. My favorite was a team of anthropologists huddled around the remains of the Ice Man, the world's oldest natural mummy, with the words "Eureka!" floating in a thought bubble above one scientist's head.

Teachers who use the DART may tap into similar richness when analyzing students' perceptions of reading, before and after teaching. They might identify impoverished conceptions of reading, or definitions that cross the boundaries of academic instruction. In either case, I would encourage teachers to think about the influence of their instruction on students' perceptions of what reading is. In our initial inquiry, as we sifted through more than fifty illustrations of readers reading in comfortable locations with, we can assume, self-selected texts, I pointed out that these images suggested students were paying attention to authentic encounters with books and using these experiences to explain their understandings of what it meant to "do reading". Cream rises to the top.

Again, I turn to Tomlinson's ten understandings about informative assessment to frame my argument about the value of tools like the DART. Tomlinson explains that,

- Informative assessment isn't always formal. [It] could occur any time I went in search of information about a student. In fact, it could occur when I was not actively searching but was merely conscious of what was happening around me . . . I began to sense that virtually all student products and interactions can serve as informative assessment because I, as a teacher, have the power to use them that way (p. 9).

The DART was attractive to teachers in my study group because they were "conscious about what was happening around them" and they were uncomfortable with that consciousness. Looking more closely at the influence of a scripted reading program on students' definitions of what it meant to "do reading" was exactly the kind of inquiry these teachers needed to do to gather evidence about their misgivings. Like Tomlinson, they used the DART to explore their questions because they had the power to do so. The world offers many opportunities to connect the power of teaching to learning opportunities for students. The potential of inquiry through informal assessment is one way teachers use their power to transform teaching and learning.

References

Atwell, Nancie. 2007. The Reading Zone. New York: Scholastic Professional Books.

Nuno, J. 1998. Draw a Scientist: Middle School and High School Students' Conceptions about Scientists. USC Rossier School of Education. www.jdenuno.com/Resume%20Web/DAST.htm.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2007-2008). Learning to love assessment. Educational Leadership (v. 65, n. 4). pp. 8-13.