“Let’s go around and introduce ourselves,” says the facilitator in a recent class I attended. This is a common occurrence at workshops and conferences. When my turn comes, I will be ready to answer with my spiel: “My name is Gigi McAllister. I teach fourth grade in Gorham.” But then the facilitator throws me a curveball, “. . . and share with us your favorite literary heroine.”

Suddenly my brain goes fuzzy and blank, my ears are buzzing, my heart pounds, and my breathing quickens. It feels like someone has turned the thermostat up about 20 degrees, and I am certain that my face is a glowing red as I search my brain for a response. Thankfully the introductions begin on the opposite side of the room from where I am sitting, but I am unable to learn anyone’s name because I am desperately trying to think of a female heroine, any female heroine. Surely, as someone who reads fiction often, I can think of my favorite heroine.

Muffled voices seem to come from far away, saying, “Jane Eyre,” “Elizabeth Bennett,” “Nancy Drew.” My turn is coming soon. I need to think of something quickly. Then as all eyes turn to me, I squeak out “Hermione Granger.” (At the time I was not even sure that Hermione Granger was my favorite heroine. She is, but that was irrelevant.) I am able to start breathing normally again as the next person starts sharing.

I chastise myself as we move on with the next activity. My negative self-talk goes something like this: What is wrong with you? That was an easy question. No one else seemed to have trouble thinking of an idea. You are a professional—get a grip.

I chalked it up to nerves, because I can sometimes be quiet in a new group of people, and tuned in to the speaker.

As the day progressed, a few partner brainstorming activities did not go well. We were asked to brainstorm a few lists that might help guide our writing for the day. To my great embarrassment, I was simply unable to think of much to offer my partner in the two minutes we were given.

Later in the day we discussed Donald Graves’s book Testing Is Not Teaching. An entire chapter of his book is devoted to slow thinkers. He discusses how many of our greatest thinkers were slow thinkers who needed more time to ponder ideas and questions than many people. He also discusses the fact that slow thinkers are not as highly valued in our society (or classroom) as fast thinkers.

Right there in the middle of class I had a huge “aha” moment: maybe I am a slow thinker. I have trouble thinking on the spot. I am terrible in interviews, but can often give thoughtful responses if I am given time to mull things over. It is not that I need to process the question; I need time to process my response. This can often make me look like I am unsure or tentative, because I don’t respond right away. Speed, efficiency, and quick decision making are valued in our society, but not everyone thinks that way.

This realization got me thinking about slow thinkers in the classroom. Are they struggling from anxiety during tasks that ask for quick thinking? Are they unable to process what is happening around them as they search for a response? Of course they are.

To help our slower thinkers, we first need to recognize them. Slow thinkers may exhibit some of the following traits:

- Difficulty with on-demand writing or responses.

- Physical signs of trying to concentrate: looking up at the ceiling, sighing, rubbing their eyes or face, laying their head on their desk, and even pounding gently on the paper.

- During a writing period they may sit for a long time or share that they can’t think of anything.

- They seldom raise their hand to ask or answer questions or are quick to say, “I don’t know” or shrug.

- During a sharing time they may not have something to share, but they may think of something at the end of the session or after the period is over.

- Sometimes slow thinkers appear to be shy, quiet, or unsure.

Once we take a look at our classroom population and recognize our slower thinkers, we can do some things to help them in the classroom.

Cue Them In

Let slow thinkers know what will be happening before an activity begins.

If the facilitator of my class had written a schedule on the board with a brief sentence about what we would be doing throughout the day, things might have gone better for me. In the classroom, teachers can touch base with their students either as a whole class or individually about what they will be asked to do during a particular period.

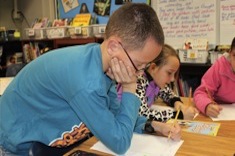

This could mean that in the morning the teacher leans down to Johnny and tells him that the class will be doing a quick-write about a time students were proud of themselves. For his morning work, he can have some time to think about a list of ideas. Or a few minutes before a morning meeting, the teacher can let the student know that they are going to be sharing calming strategies they use when they get frustrated. Sometimes this little “heads-up” can give students time to think so they will be ready to participate.

Provide Choices

During writing workshop Sally sits with seemingly no idea what to write. For some students too many choices can lead to making no choice at all. To help during this situation the teacher could ask others in the class to share their current topics and chart them for everyone to see. One student’s idea may spark an idea for Sally. Or the student may need the teacher to limit the choices for him. If the teacher knows the student well, he or she may be able to provide the student with limited choices. “Today you can write about getting your new dog or how you learned your special talent for drawing cartoon characters.”

Extend Time

It may sound obvious, but sometimes extending an activity by a few minutes can help slow thinkers. Instead of taking two minutes to brainstorm, try four. Instead of having 20 minutes of writing time, try 30. It is frustrating for a slow thinker to have to stop an activity just as they are finally getting started.

Using “wait time” can also be helpful when asking questions or soliciting responses. The teacher can try waiting while the student thinks, but this focused attention can be stressful on the slow thinker. As with the examples from my experience, more anxiety does not help slow thinkers think clearly. Sometimes I feel that it is more effective to use a “boomerang” approach by asking a question and letting the student know you will come back to them in a minute. Take other comments or questions from the other students and then return to the slow thinker.

Then there is the “phone a friend” option: the student can choose another student to help them, but the slow thinker should be the one to respond or repeat the response. It is important to help the student answer or respond successfully. This shows them that you value their thinking process and that you will provide the necessary support for them to participate successfully.

Foster Self-Advocacy Skills

Teachers can show respect for slow thinkers by teaching them how to advocate for their needs. Teach slow thinkers to

- ask for extra time;

- ask to start early;

- ask what will be happening during a given period;

- say, “Come back to me” or “I need a minute”; and

- use relaxation techniques to curb anxiety.

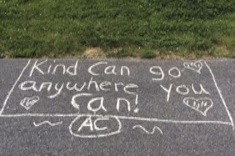

Students need to know that all types of learners and thinkers are valued in the classroom. Having a private discussion about what you are noticing, and educating the student about their way of thinking, can be very powerful. Teaching them to ask for what they need in the classroom shows that you value their way of thinking and empowers them to take control of their own learning.