Over the last four years our teaching staff has included reflecting on student work as a part of our staff meetings. To be honest, we struggled for probably three of the four years to find meaningful ways to look at the work. You may read this and wonder how we could be so behind the times – hasn’t everyone been doing this effectively for years? But the truth is, this has been a process in which we have been revising and now fine-tuning our routines for making the most of our discussions about student work.

Here is a glimpse into our journey . . .

Bringing Student Work to the Staff Meeting

When we first asked staff to bring samples of student work into meetings, the request was very open-ended. We wanted teachers to have ownership and flexibility with the task. But the reality was that our first real challenge was for staff to actually bring in student work – even though it was on the agenda, few colleagues chose to bring anything or share it.

Gradually staff started bringing in samples of student work . . . all kinds of student projects and writing. It was difficult to focus discussions when everyone brought in different types of work samples. Work ranged from graphic organizers, reading responses, and post-its filled with thinking to writing journals. It also seemed in the beginning that teachers brought work samples that showcased best efforts from the brightest students.

Our conversations were clunky. We really didn’t have a framework or goals. We seemed to talk about the strengths we saw in the work, but the conversations around the work ended there. We never talked about next instructional steps. The next meeting found us looking at new samples, still struggling to focus in any meaningful way on how these glimpses of students could inform our instruction collectively.

Student Work Through the Lens of School Goals

Over time, we began to link discussions of student work to school goals. We thought if we were talking about the same type of work samples, we would have more productive conversations. It was definitely a step in the right direction having staff bring in work around a common learning goal. But in the end, our conversations were still superficial. We glossed over the content, and somehow always found ourselves focused on the spelling and mechanics in the work samples, because these were easy (and glaring) needs to highlight for any student. Our conversations traced the path of what we were doing as teachers, rather then what we saw students doing in response to our instruction.

Protocols

Next we tried protocols, in hopes these would guide us through student work. In reality, the protocols stifled our conversations. The focus seemed to shift from the student work to covering the components of the protocol and keeping track of time. Any natural conversation was halted. We knew a major change in our thinking and procedures were needed.

Rethinking Our Goals

One of our biggest mistakes in the beginning, and throughout the process, was that we did not have a common understanding as a staff as to why we were actually looking at student work. We should have started with a simple question – What did we hope to gain from discussions of student work?

Our leadership team considered this question, and decided we wanted to be able to use student work to inform our instruction. Our goal was to collaborate with colleagues on some of our students that we struggled to reach. With this goal in mind, we developed a new template to guide our conversations. We worked as a leadership team to create this simple but universal tool for looking at student work from any classroom in any subject area. We have revised this template repeatedly this year, tweaking language and layout. You can download the template by clicking here.

Finding Success

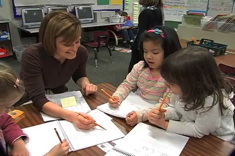

We had a teacher model the use of the student work template for the staff for two months in the row. The first month she shared an overhead of a reading response from one of the students. She explained her learning goal for the student –Â determining important information in a biography. She identified what she saw as strengths and weaknesses — the student had basic information about the person he was studying, but struggled to identify the relevant details that supported why the person was famous. Our staff brainstormed instructional strategies that might be tried with this student. It is still interesting to note that several comments were made about the spelling and mechanics of the piece.

The next month she brought back another piece of work from the same student. She modeled how she took the learning from the first month, retaught her student strategies to determine important information in biographies, and then monitored progress through literature discussions and reading responses. She shared another response to reading. This time she typed it up and began by explaining that she knew that the student needed support in spelling and mechanics. But since her learning goal was determining important information, she typed it for us so that we would not be distracted by the student’s handwriting or spelling, and instead could focus on the learning goal.

The other key to this process was that we were starting to look at the same student over several months. We wanted to use this time to support some of our neediest students. This meeting was a turning point in how we started reflecting on student work. We finally had a clear framework for talking about students.

You may view our evolution of reflecting on student work as a comedy of errors. But I view our process as an authentic collaborative learning process. We found that using a student work template with guiding questions is an effective tool for focusing our conversations. It truly has been a group effort to figure out how to best incorporate student work into our meetings. We have learned how talk about student work in a way that makes sense to us.