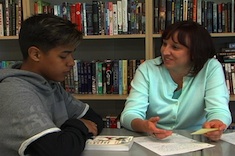

“How often do you confer with readers?”

I get asked this question a lot. In fact, I work with a close friend of mine who, before I can answer that initial question, follows it up with, “And how long are your conferences? Because if each conference is seven minutes long, that means I can fit in about three conferences a day, which means I can meet with each student only once every two weeks, but if you factor in days off and early release days, then it is only…” You get the idea. You may even know my friend.

This line of thinking is practical. It makes sense to want to make a schedule, to ensure that every student gets individual attention. However, I find that if I begin my planning for conferences by calculating minutes, I feel hopeless before I even start.

Instead of working on a mathematical equation to schedule my time, I plan ahead to make conferences as brief as possible to fit in as many students as often as possible, to take up as little of the time students could spend actually reading as possible.

Although conferring helps me get to know readers better, I try to enter conferences with some knowledge in hand. To gain this knowledge, I collect and analyze student responses to reading. That way, I can identify and name the thinking students are already doing as readers, and make preliminary decisions about where they might go next. These are the most helpful kinds of reader responses I have used.

Storyboard

One way students respond to texts is by completing storyboards as a means of retelling a story. They use storyboards at the end of a chapter, short story, or book to practice determining importance. By sketching stick figures and writing dialogue and/or descriptions, students demonstrate the depth of their comprehension. I can look at a storyboard and see if a student has connected important details to determine deeper meaning, if their comprehension is surface level, and if it is even accurate. This gives me a starting point in a reading conference. If basic comprehension is lacking, I know that is where I need to start.

Sketchnotes

Although some students prefer the structure of storyboards, others enjoy the freedom of sketchnotes. Sketchnotes can be completed during reading, but I usually urge students to wait until they reach the end of a text to capture their thinking about the story as a whole. Any combination of words and images can be used to create sketchnotes. By looking at student-created sketchnotes, I get an idea of what images, symbols, and themes stood out to the reader. I can also see whether the reader is connecting parts of the text, such as characters or events.

Annotations

I frequently ask students to annotate text, which I explain as adding notes to a text to explain or comment. From time to time, I ask students to annotate the page they are currently reading in their independent choice book. I brought an old printer to my classroom that has lost its ability to do two-sided printing but is perfect as a copy machine for students to make a hard copy of their current reading material to add annotations they can share with me. In-the-moment annotations give me a window into the kind of thinking students are doing without prompting. In the absence of a printer, I have used Cris Tovani’s inner-voice sheets, a double-entry journal, or sticky notes for students to record thoughts.

Big Ideas

Another response that is effective at any point during reading is to have students select a big idea they believe connects to the text they are reading. I push students to name the big idea (for example, friendship, change, or sacrifice) and three ways in which it appears in the text. When I write about big ideas in texts I am reading, I find that naming three connections usually pushes me beyond the obvious and helps me develop new thinking. Big idea entries reveal whether readers are able to move beyond summary into textual analysis. I can see if a reader is focused on character, setting, plot, or all three.

Written Conversations

Occasionally, I want to see how students interact with others about text. The simplest way to capture these exchanges is through written conversations. Each student begins a conversation by writing a paragraph or so, capturing their thinking about a text, then passes the paper to another student. We usually pass among two or three students so they have a chance to respond to one another, rather than passing to six different people. Written conversation gives me insight into what a reader could do to take interactions with other readers to the next level.

Video

More recently, as our students have gained one-to-one access to Chromebooks, I have added video-recorded responses to my menu of options. We use platforms such as Flipgrid or VoiceThread to record responses to general thinking prompts such as “What challenges is the protagonist facing at this point?” When viewing student responses, I make note of the thinking I notice students doing. I can see who struggles to come up with ideas or articulate their thoughts, which gives me an idea to bring to a conference.

Informal Letter

Sometimes, I get the best insight simply by asking students to write to me. I prompt them to share what they are thinking about the text they are reading, and remind them to move beyond summary if possible. Occasionally I may give students a more specific prompt such as “What is one thing you are wondering about as you read?” This open-ended invitation can help lead conferences in many different directions.

Once I collect responses, I analyze them to make plans for conferring with each reader. For instance, Amy completed a storyboard based on the novella Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes. When I analyze her work, I notice Amy demonstrates accurate comprehension of multiple storylines and that she understands the importance of the flashback, though she is not necessarily connecting it to later events. As a result, I make a plan to begin her conference by pointing out how sophisticated it is that she noticed the flashback and to ask some follow-up questions to see how I might be able to help her deepen her thinking about the purpose of flashbacks. I might begin with, “Why do you think the author included that flashback?” or “How does that event connect to what happens later in the story?”

Most of the time, the idea I have in mind when I sit down next to a reader does not change in the course of the conference because I have spent the time analyzing responses in advance. However, I always enter a conference with a willingness to shift directions based on student responses.

While analyzing reader responses, my focus is on individual needs. Sometimes, though, a pattern emerges and I recognize the need for a whole-class minilesson. In this case, I will likely teach the minilesson to all students and follow it up in individual conferences as needed.

Analyzing reader responses outside of class time allows me to begin each conference by jumping into the middle of a conversation with a reader. How often do I confer with readers? Much more often since I started planning ahead.