“I don’t remember how to do that!”

“We talked about this before. How we can make our characters come alive by adding conversations in our writing? Or using speech bubbles in our drawing? Do you remember how to do that?”

“Ah yes, speech bubbles!”

“Right. So are you going to try it now?”

“Maybe.”

SIGH.

When I conferred with these second-grade English learners, all I seemed to be doing was reminding them of what we’d learned so far in writing workshop. I could hear myself saying over and over again, “Remember we talked about . . .” and “Have you tried using some repetition in your writing?” or “We learned all about quotations, but I don’t see you using any in your writing yet. Why is that?”

The beauty of working with young writers is that they find everything I teach new. The challenge of working with young writers is that their short attention span makes it harder for them to try many of the strategies we learn. By the time they sit with paper in front of them, their memory of a new strategy is replaced by the excitement of the blank page.

It’s still a beautiful problem to have.

How can I help my young writers actually try some of these writing strategies, especially in the middle or by the end of the year? By then, they have been introduced to many different strategies they can use to elevate their work.

I decided that to create an accountability system, I’d first need to spend some time reflecting on what they were already doing as writers. I decided to take five writing folders home throughout the course of one week so that I could do this work without interruption. I opened a new Google Drive document and created a chart that looked like this:

| Using speech bubbles | Showing how a character feels | Showing what a character is thinking | Using onomatopoeia or sound words | Using repetition | Using descriptive words in our writing | Using any of our 5 senses |

In this chart, I tried to list every minilesson that I had taught so far on using writing strategies that make our reading come alive. Every time I took folders home, I would read each student’s work and put their names in the column that showed what they did as a writer.

I started with this system because I wanted to celebrate what they were already doing. It’s important to build writers’ confidence, especially as they try new things. After completing this work over the course of a week, I had a clear idea of who needed to work on what. But before I challenged them, I took some time to celebrate their writing during sharing time.

Conferring with a Plan

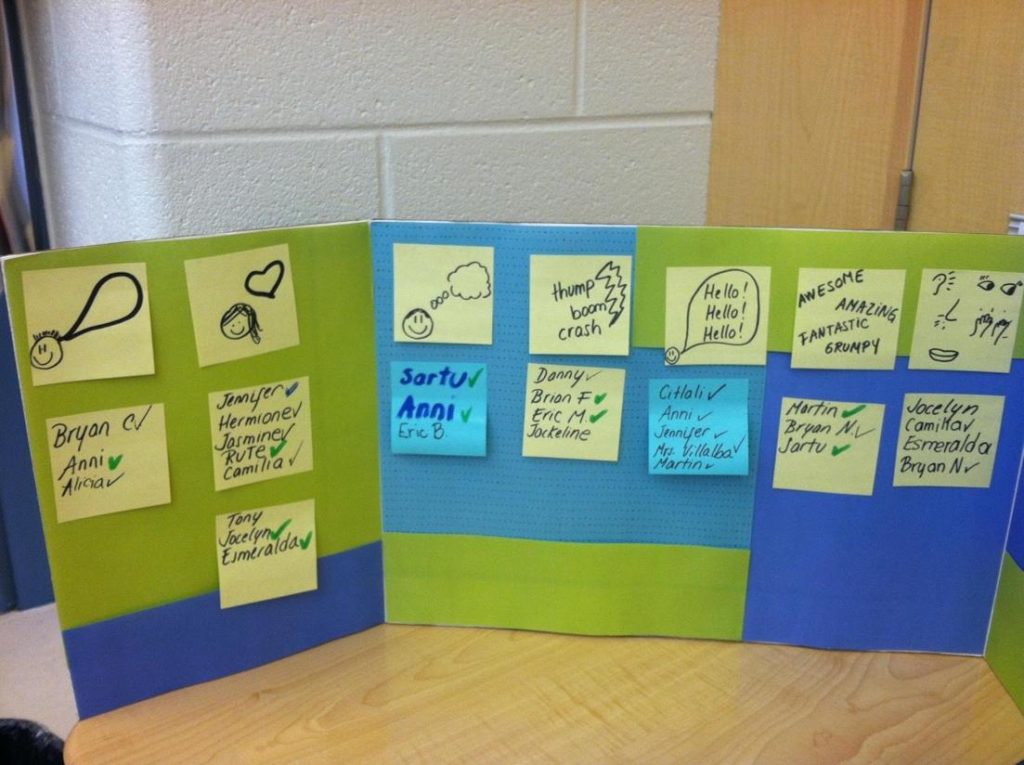

Once I had this chart on Google Drive ready and had taken some time to celebrate our young writers, I was ready to confer with them with a very clear plan. I had taken the pulse of where my young writers were in terms of applying new learning. However, my Google Drive chart was very not child-friendly—or inspirational, for that matter. It was a tool for me, but it was definitely not a tool for them. So for one of my minilessons in writing workshop, I decided to review with the students all the strategies we had learned so far. As they listed them, I drew a picture that represented that strategy on a sticky note. I put all of those sticky notes on a trifold chart that I kept on one of the tables during writing workshop.

During the minilesson I told the students, “Look at how much we have grown as writers this year. We have so many tools in our toolbox to choose from. I want everyone to look at the chart, think about a strategy you haven’t tried yet, and then give me the thumbs-up when you are ready to tell me your new goal.”

As each writer told me what they would be working on during the week, I added their name under that strategy. I reminded each writer to please let me know when they had achieved that goal. I would not only add a check next to their name, but make sure we celebrated that writer on that day.

When I met with each writer, I no longer had to remind them what they were working on. I didn’t have to spend so much time asking them to think of a goal. They knew what to do. They were in charge of letting me know when they had applied what they’d learned.

This small but wonderful change allowed my writers to keep themselves accountable for their own learning. It also allowed me to have different conversations during conferring instead of constantly reminding them what we had learned. It shifted my thinking, and it shifted the way they worked. I had fewer sighs of frustration in conferences because I couldn’t see evidence of transfer from the minilessons. We all grew a lot as writers and learners.