One of the most important life lessons that writing and reading poetry can teach our students is to help them reach into their well of feelings—their emotional lives—like no other form of writing can. It can also help our students open their eyes to the beauty of the earth, restore a belief in the power of language, and help them begin to understand the truths inside them.

Georgia Heard

Every Thursday, no matter what else we do in reading workshop, we set aside time for poetry in our sixth-grade classroom. For about 20 minutes, we read over a poem we had “unpacked” and responded to for homework, and share our thoughts about what the poem conjured, how it evoked beautiful images, the way it sparked our imaginations, and how it spoke to our hearts. Those 20-minute stretches have inspired deep conversations, laughter, and wonder; this is often where we find issues to question and want to write about, and where we find our own poet selves hiding, waiting to be discovered.

We begin our study of poetry the very first week of school, so that my students know that it will always be an essential part of every week of our year together, and we do so with a simple review of poetic devices: the tools in a poet’s toolbox. I adapted the handout below from Read, Write, Think, which gives my kids simple and clear definitions for understanding poetry:

We “unpack” a poem in class together, and I invariably choose this one, by Marci Ridlon, because (of course) my students are mourning the end of summer, and Ridlon’s poem captures summer perfectly:

|

That Was Summer—Marci Ridlon Have you ever smelled summer? Sure you have. Remember that time when you were tired of running or doing nothing much and you were hot and you flopped right down on the ground? That was summer.

Remember how the warm soil smelled and the grass? That was summer.

Remember that time when the storm blew up quick and you stood under a ledge and watched the rain till it stopped and when it stopped you walked out again to the sidewalk, the quiet sidewalk. Remember how the pavement smelled— all steamy, warm and wet? That was summer. |

Remember that time when you were trying to climb higher in the tree and you didn’t know how and your foot was hurting in the fork but you were holding on tight to the branch? Remember how the bark smelled then— all dusty dry, but nice? That was summer.

If you try very hard can you remember that time when you played outside all day and you came home for dinner and had to take a bath right away, right away?

It took you a long time to pull your shirt over your head. Do you remember smelling the sunshine? That was summer. |

This collective “unpacking” gives us a chance to get the feel of reading a poem closely, taking it apart, and appreciating the poet’s craft. It also allows us to begin conversations about poetry as we discuss what we liked and the way the poet created sensory details and imagery. This type of talk is mirrored and magnified in our reading and writing workshops all year long as well, so my students come to see the craft of poetry embedded in all beautiful writing—in the books they read and in their own writing.

We create a “How to Unpack a Poem” chart for our classroom, which becomes a handy reference sheet in our poetry notebooks, as well:

And that sets us up for the rest of the year: a poem to unpack, discuss, and inspire us to feel, think, and then respond to every Thursday. Here’s an example from Jasmine’s poetry notebook, which shows how she grew her unpacking from noticings to response to a poem of her own:

We range all over the poetry world to find poems to respond to, both geographically and thematically. Quite often, the choice of poems is inspired by what we are learning about in social studies or events that are taking place in the world. And, quite often, my students bring in poems they have discovered on their own, or the lyrics of songs they find powerful. No two poetry years look the same or sound the same in our classroom, for that is determined by the needs and voices of the children who fill its space.

I find that my students become close readers in a most natural way, and that they develop a confidence in what they notice and respond to, as Jasmine demonstrates here, when she feels that the last lines of the poem did not reflect its true depth:

Sometimes, we borrow ideas from poets who have found beautiful ways to respond to art and photography, as we did with Cynthia Rylant’s brilliant book Something Permanent, which was inspired by the haunting Great Depression-era photographs by Walker Evans:

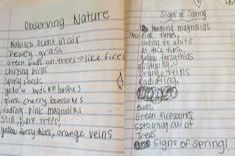

And, when the weather permits, we escape our classroom for a spring walk to collect observations and craft poems of our own:

Immersing ourselves in the study of poetry takes many shapes and forms in our sixth-grade classroom. It is such a worthwhile way to explore the essence of literacy, what the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge noted as “the best words, in the best order.” Just 20 minutes, once a week . . . Such a great investment!