A group of first graders we work with is reading level M texts independently in late winter. Although the texts they’re ready and able to read have more complex ideas, they are still first-grade readers: they can’t help but bookend their reading with personal stories that are (mostly) unrelated to what we’re reading, they think the most interesting texts are those with cool and surprising facts rather than new ideas, and any behaviors outside reading the text (such as pausing to think, talk, and write about what they’re reading) require many prompts and reminders.

The challenge we’ve faced recently with this group is that, to read the texts at their independent level well, they need to be pushed to think about them in a way that is completely new for many first graders, because they just don’t think that way as people yet.

One way we’ve begun to nudge them toward thinking more deeply about their texts is to work on supporting their ideas with evidence. Thinking about feelings seems to be a comfortable place to start for our first graders, so that’s where we decided to introduce the idea.

Here is our process.

- Introduce the concept of ideas being supported by evidence, and give students a chance to try it.

We used boxes and bullets as a way to organize our thinking about ideas (i.e., we put an idea in a box and used bullet points for evidence), and scaffolded the work by giving students an idea that we knew they could identify with and understand: that a character was feeling worried. We asked the students to look for evidence—things the character said, did, or thought—that showed she was feeling worried. We provided an additional scaffold by sketching an icon for each of these types of evidence on the sticky note they’d be writing on.

In the group of three students, one repeated how the character was feeling, one described how the character looked, and another named an action with some support. After watching how the students struggled with finding evidence during their reading time, we decided our next step would be to look more closely at what they could do when they were supporting their ideas with evidence through a mini-inquiry.

- Create a mini-inquiry and guide students through it to create a continuum of evidence.

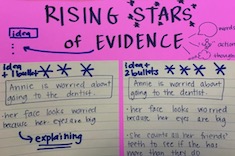

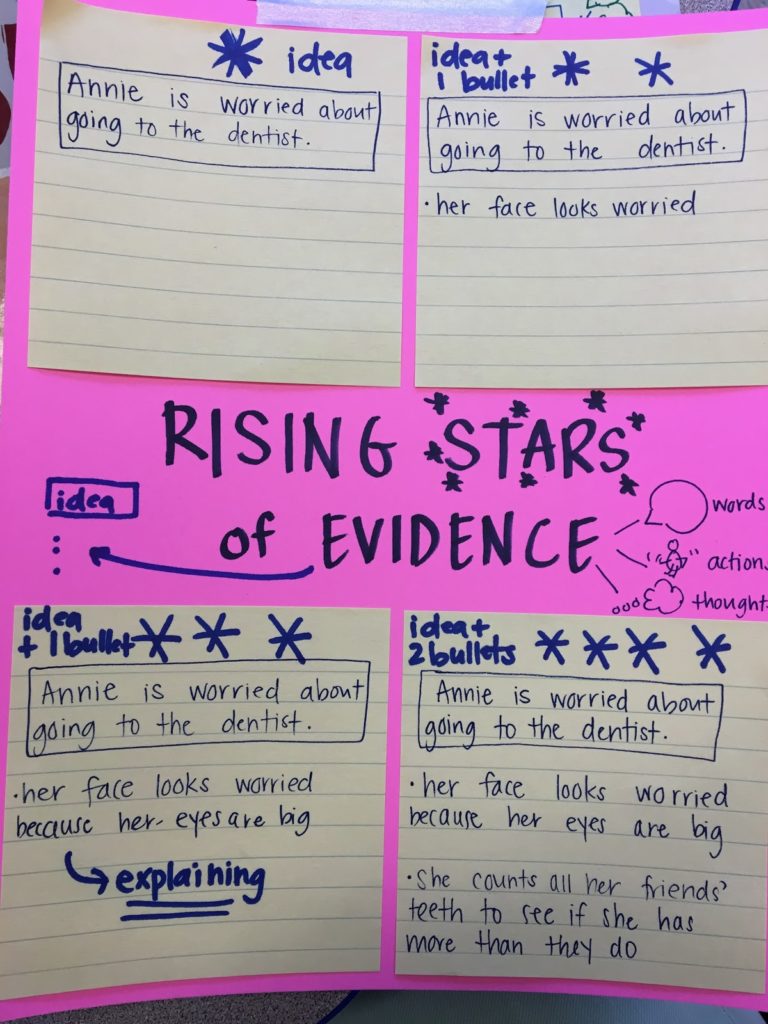

Using the same text that students had read, and the same idea they had been given, we created four different levels of ideas with evidence. A level one was just the idea, level two was an idea with one piece of evidence, level three was an idea with one piece of evidence that was a little more detailed, and level four was an idea with two pieces of evidence. We kept the idea the same across the sticky notes and used the same evidence every time we could. We arranged the sticky notes in random order so that students would have to read each one and determine the progression.

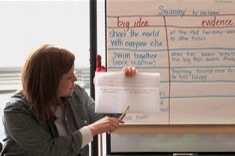

We introduced the mini-inquiry by reminding students that supporting our ideas with evidence makes them stronger, and asked them to help us give one to four stars to each of the sticky notes. As students leveled the sticky notes, we added the stars and talked about descriptors that could be used for them to replicate the work. After we had leveled and labeled each sticky note, we rearranged them so that they were in order. Our finished continuum is below.

The darker and larger writing on each sticky note is what was done during the mini-inquiry, using what the students noticed and named about each mentor sticky note.

When making the sticky notes that would serve as mentor examples for the chart, we made sure to have one that matched where our student who was having difficulty with the work (a one-star sticky note, with just an idea) was, as well as where we knew our students could be pushed toward with some work.

- Invite students to try the work independently again, using what they learned from the inquiry.

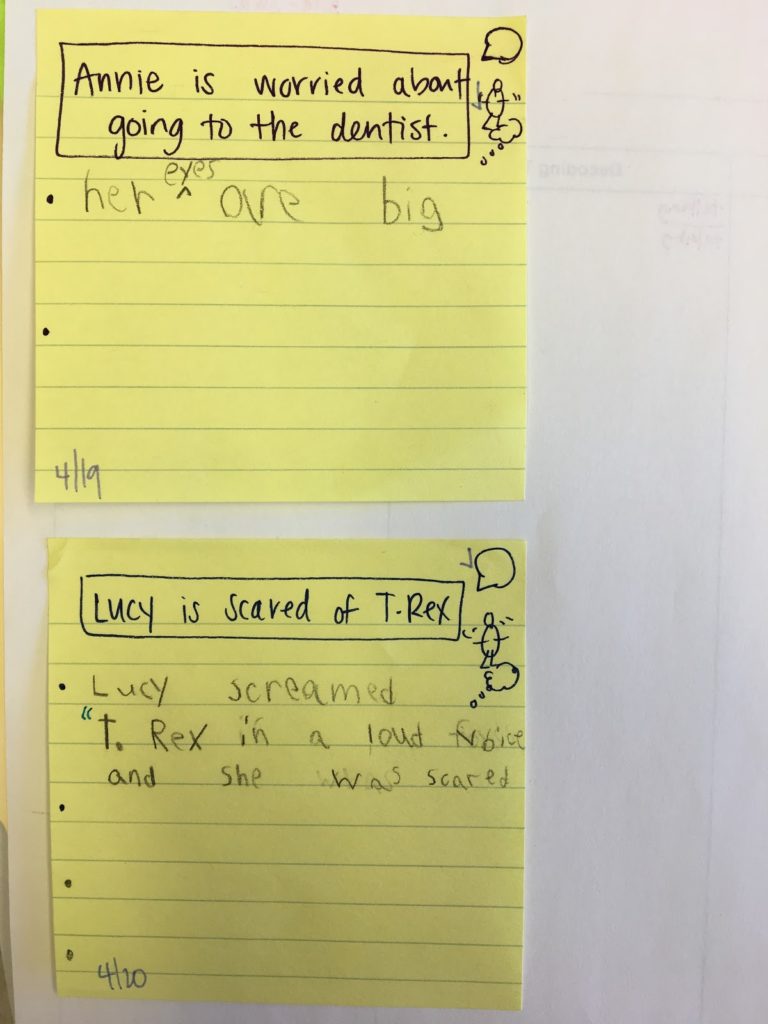

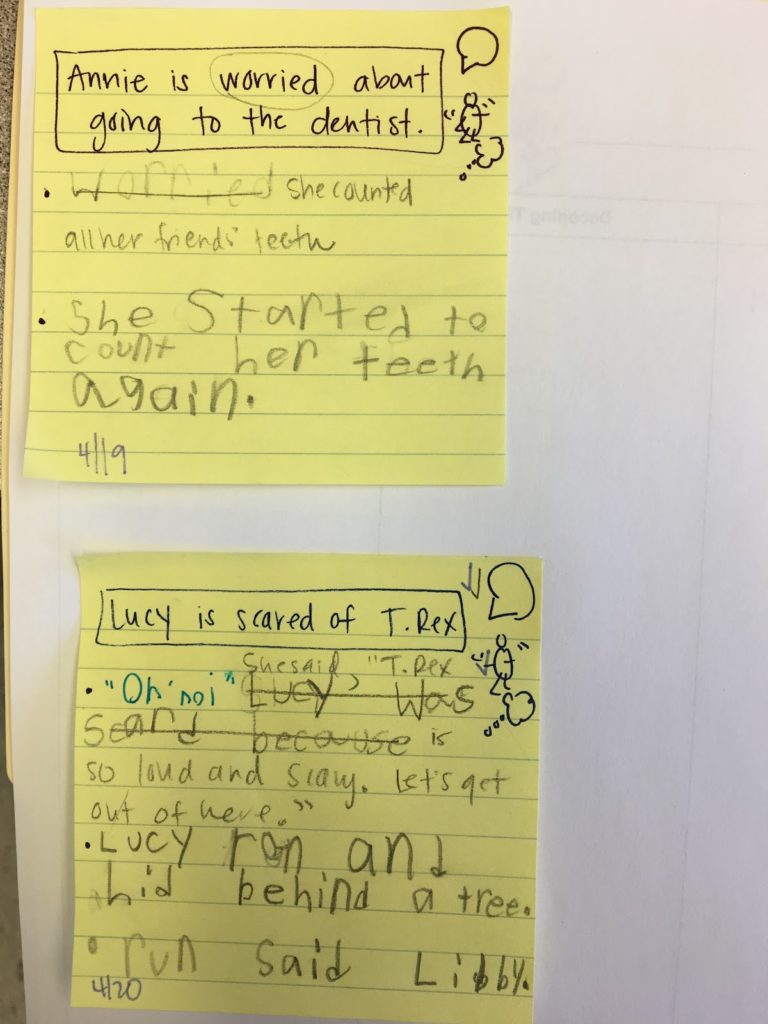

After completing the inquiry together, we had students look at their idea-with-evidence sticky note from the night before, and reflect on where they were. We emphasized that being a one-star sticky note is okay because we have the chance to grow; that is, it’s not our level that matters, but how we’ll push ourselves to grow. The three students in the group placed their work at a one, two, and three star.

We gave students another sticky note with an idea already written for them—another idea about a character’s feeling—and invited them to find evidence again as they read their new book. Two of the three students showed immediate growth, each moving themselves one step along the continuum (one student went from a two to a three star, the other from a three to a four star). Their sticky notes are below; the one on top is their sticky note from the first night, before the inquiry, and the one on the bottom is their work after the continuum was made.

The darker and larger writing on each sticky note is what was done during the mini-inquiry, using what the students noticed and named about each mentor sticky note.

The third student is able to identify evidence when supported during a conference, but not yet independently.

The value in the inquiry and the tool that comes out of it in the continuum is that for many students, having a vision of what more sophisticated work looks like is enough for them to push themselves toward the work even without teacher support. It also gives us information about who needs additional support, like the third student in our group.

Once we’ve gotten to this point, we have many more opportunities to support students with this work in an ongoing way. Every time they read, we pull out our Rising Stars of Evidence chart for them to use to support their writing about reading, until it becomes more automatic for them. By using the chart over and over again, students are given chances to reflect on their sticky notes (how many stars would this sticky note get?) and set goals for themselves to continue to push their thinking and writing about reading. We also give opportunities for guided practice through read aloud, which is especially important for the student in the group who didn’t move as independently.