This year I attempted to do something I had never tried before in my teaching career . . . planning and following through with a partner writing study, a study that I would teach and learn from with 125 sixth graders. In years past I had always supported children in their quest to write "partner books" or work with a partner on a single piece of writing, but I had never intentionally planned a unit where all students would think, talk, and write with a partner for the entire unit of study.

On top of that, I decided I would pair the students randomly for this writing study. Why in the world would I torture myself like that? And more importantly from the sixth grade point of view . . . WHY, Miss Corgill, would you torture us like that?! You can so imagine that I got lots of groans and eye rolls and "are-you-kidding-me?!" response from sixth graders when I announced this idea in my best, most enthusiastically cheerful teacher voice.

Why random pairing? While random pairings are risky, there are also perils to having students pick their own partners. I choose random pairings:

- to increase students' engagement and accountability for participation

- to help students learn to work together, develop social skills, and take responsibility for their learning

- to learn how to regularly plan for, discuss, and solve problems related to their work together

- to cultivate a working environment where students think about and act on the core values of responsibility, respect, caring, fairness, and helpfulness for all

Wispy blonde haired beauty pageant girly girl Madison (who's paired with CarsonCouldCareLessAboutGirlsandWriting) looked me dead in the eye and said emphatically, "This is never going to work." I got looks of pure disgust from these on-the-verge-of-hormonal teens who would rather eat dirt than work with somebody who's not a "friend" and not of the same sex. In my best, most enthusiastically cheerful teacher voice, I said again "I'm doing this because I'm going to push you out of your comfort zone, I trust you, and I believe that you can do it."

The key words here are believe and trust. When things in our teaching lives and in our students' learning lives seem difficult or even impossible, the first and most important thing we have to do is believe that it is worth our time, that the successes of this work will outweigh the failures, and that students can and will grow from the experience.

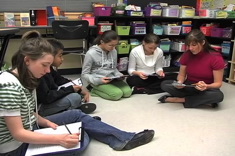

Collaborating to Choose a Topic

My students had been reading lots of nonfiction and recording possible writing ideas in their writer's notebooks for days. Every child had topics they were passionate about and ready to write about in depth. Then, I put a kink in the plan. After randomly partnering each class of writers, I said, "Now it's time for you and your partner to choose a topic that you are both passionate about researching and writing. One topic for both of you. Can you imagine the groans and the "this is going to be too hard!!!" comments I got? . . . Yep. They abounded in every single class.

I trust you. I believe that you can do it. I can't wait to see how creative you'll be in meshing topics and making this work for both of you. That was my mantra for my writers in all four classes.

Madison was convinced that the only topics she could and would write about were music and dancing. Carson laughed in her face and stood strong behind his basketball topic. It was war. All I could do at this point was continue to whisper in their ears . . . I can't wait to see what you will do to make this work. Over several days of scouring their notebooks and having conversations about how they might make this work, they did. Their new idea? Their nonfiction book would be a compare and contrast piece called "The Two Michaels: The Story of Michael Jackson and Michael Jordan." This would be a book about Famous Musician/Dancer AND Basketball Star. Madison and Carson were beside themselves with pride and satisfaction, and were ready to read, research, and write an amazing nonfiction book.

Because of odd numbers and a sick student for a few days, one group became a team of four writers. Hannah, Will, Justin, and Rachel were positive they would never come to an agreement. Hannah was passionate about religion. Will wanted to research extreme weather situations. Justin is the next David Macaulay and was dying to dig into every book he could find about architecture. Last but not least, Rachel, a girl after my own heart, loves clothes and wanted to write about them. What did they come up with? Ancient Egypt. It was a perfect topic to tap into each of their passions and teach them about a place in our world they never even dreamed possible when they started this process.

What's cool is that I had four classes full of stories just like this one. The students stepped up to the plate, took big social and academic risks, pushed their thinking, and came up with brilliant ideas.

If you want to try a partner study yourself, here are some practical tips to get started:

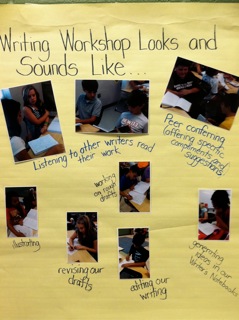

1. Begin a writing partnership study well into the year after class norms, routines, and writing workshop expectations are clearly in place so students don't become overwhelmed with too many expectations.

2. Give students time before the study officially starts to read quality nonfiction texts and jot ideas, passions, and research interests in their writer's notebooks. Students must be readers of the genre before they can write well and need time to gather their ideas and thinking around topics of interest. This work also gives partners a place to start their conversations when working together.

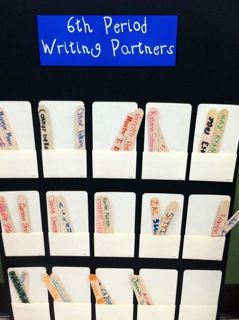

3. Portable foam board partner charts work well to keep me organized and the students aware of their partners and other partnerships in each class of writing. It's an easy way to change groups of students who will work together in different ways over the course of the year.

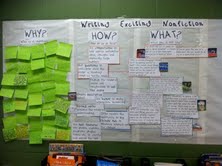

4. A "Why? How? What?" anchor chart is beneficial in guiding all students through the study and gives them a reference to refer to when writing and working together. WHY is it important to write engaging nonfiction? This section of the chart includes students all responding with their personal reasons to write for an audience of informational readers. HOW do we do that? This section of the chart includes specific examples from mentor texts. WHAT does it look like once it's done? This is where students share their work.

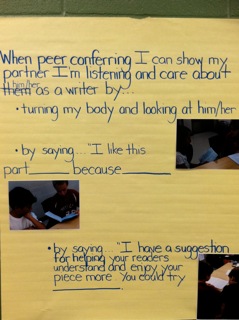

5. Students will need lots of support and reminders for how to work together, talk together, and write together. Co-create partner work or social skills reminder charts to refer back to throughout the study helps.

Besides the academic expectations of this project, I knew that there would be lots of social teaching that must go along with it, and this social/emotional teaching would be equally important to the writing work we would do. My friends at the Developmental Studies Center encourage partner studies, and they've made me rethink the importance of the social development of the child. I strongly believe it's that intentional attention on the social and emotional development of middle school students (and any age student for that matter) that allows these students to reach their full academic potential.