If I were to model a demonstration lesson in your classroom, the first thing I would do is ask your students to tell me their names. As they sat in the meeting area, I would make eye contact with each one and listen to each person say their name. Then I would say it back. Kids would smile and confirm, or they would correct my pronunciation.

“Your name is important,” I would remind them. “Let me know if I say it correctly.”

After six or seven kids said their names, I might go back down the line and repeat their names, associating faces and names and locking their names into my brain. If I’ve forgotten a name, I’ll ask the student to tell me again, and I’ll repeat it a time or two. This process takes two or three minutes.

From that point on, I’ll know every name in the room.

Because I teach a lot of demonstration lessons, often packing a classroom with more teachers than students, I know what one of the first questions will be during the reflection after the lesson.

“How do you remember everyone’s names?” You might wonder the same thing. Many times kids ask me before I even leave the classroom. They are often surprised that I know their names.

The simple answer is this: I listen.

Yet there’s more to listening than a quiet passivity. Listening is more than letting someone talk, leaning in, and nodding in an effort to make them feel like you are paying attention. We actually have to pay attention.

Listening is an intentional act to understand, participate, and remember. It is an essential part of conversations in our classrooms (and an essential part of conversations in life). So, how do we teach kids to listen?

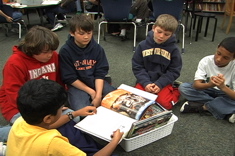

An ideal time to lean into this teaching is when students are engaged in a turn-and-talk. The purpose of a turn-and-talk is for students to engage in ideas and deepen their understanding of a concept. Here are three ways we can up the ante for listening during turn-and-talk.

Do you remember what your partner said?

Once students finish their turn-and-talk and are ready for the remainder of the minilesson, I ask, “Do you remember what your partner just said? Don’t answer that question out loud, but think about it for a minute.”

Instantly, eyes turn up and faces become sheepish. Sometimes I ask students to give a thumbs-up if they remember what their partner said. If this is the first time they’ve ever been asked that question, it is likely that most kids will not remember.

This is a prime time to teach students that the purpose of a turn-and-talk is to learn and understand more, and to do that, we must pay attention and remember what others say. Offer the invitation to return to the conversation and find out what their partners said.

Share something your partner said.

Typically after kids finish a turn-and-talk, the teacher facilitates sharing some responses. Rather than ask kids to share their own thoughts, we can invite students to share what their partners said. We might say, “Does anyone have something their partner said that is valuable for everyone to hear?”

When students share, help them use their partner’s name. A sentence frame that works well is

[Partner’s Name] shared _____________.

As students begin to expect that conversations will help them deepen their understanding, we can adjust the sentence frame to

[Partner’s Name] shared _____________. This helped me because _____________.

Don’t underestimate the power of teacher modeling in supporting students’ development in sharing others’ ideas. Before opening the invitation for students to share, the teacher can share key ideas after a turn-and-talk ends. Use the same sentence stems that you will encourage students to use later. By hearing this language before using it themselves, students will be invested in sharing other people’s ideas. They will also experience the positivity that comes when someone hears your idea and then considers it valuable enough to share publicly.

An additional benefit to asking students to share their partners’ ideas is that we hear more voices. There are students who do not like to speak publicly or do not have the confidence to share their own ideas. The students who love to take the stage and talk will jump in with sharing another’s ideas. Those who want to contribute but lack the confidence to do so will feel more comfortable giving credit to their partner’s ideas. This is a powerful way to build equity in hearing every voice in our classrooms.

Ask a question to get your partner to say more.

A satisfying conversation is one that builds upon ideas. Too often conversations in schools leap from one idea to a totally different idea. You can easily observe this if you spend a little time in the lunchroom. Don’t join a conversation, but watch from the outskirts. You will hear one student talk about the special treat in their lunch and the next talk about his dog. Another will jump in with a story about her baby brother giggling at a new toy, followed by someone telling a story about swimming in the lake.

There isn’t a thread to the conversation; it is driven by each individual’s desire to talk about their own lives. I’ve watched these conversations unfold in elementary, middle, and high school, and they typically evolve the same way. Each person talks about what is important to them, rather than listening and continuing on the same line of conversation. (This happens at my own dinner table, too!)

We can help students develop conversation wherewithal by teaching them to ask a follow-up question of their partner. Rather than jumping in with what they are thinking, they can choose to linger on the idea their partner suggested. This isn’t something humans do naturally; it is something we choose to do because we value other people’s ideas and we learn that our own thinking can deepen when we hear more from others.

I like to remind myself and students that we already know what we think. A conversation is a chance to find out what other people think. Often the best ideas aren’t the first things that are voiced; they happen after a little talking has occurred. Be the kind of listener who asks a follow-up question. A question for students to begin using is

“Will you tell me more?”

As they become stronger listeners, you will be able to teach ways to ask more specific follow-up questions.

Learning to listen is a skill we can teach and one way that time spent engaging in a turn-and-talk can become even more valuable.