I am learning how to run. It sounds silly, "learning how to run," but it's true. At first I just started running a minute, walking a minute. Eventually, I ran more minutes than I walked and then I was on my way. But after two years of "running" and not getting much further than three miles with an occasional 10k, I had gained 20 pounds. That doesn't sound right, does it? "Gained" and "running" together in the same sentence?! It's like "doing writing workshop" for two years and having nothing to show for it but maybe a few more ditto sheets. It just doesn't make sense.

I was meandering around a bookstore this spring and found a new section — at least it was new to me. There were shelves of books about fitness. Even more interesting were all of the books about running. Yes, books — plural, as in there is a market for this. My first thought was, "running is boring enough without having to read about it." I didn't have a second thought about it and I left.

The next day at school a substitute came by and said she noticed I hadn't been running as much in the neighborhood and thought I might like to read a couple of books. You guessed it, books about RUNNING. So I did, and I expected to gain weight as I read with my feet up, munching Cheetos. The books were actually fascinating. I learned more about running than I ever knew there was to learn. There are ways to breathe, different kinds of runs, and different kinds of feet which require different kinds of shoes.

Writing and Running

Okay, so what does this have to do with writing? EVERYTHING. Whenever we try to implement something new — whether it's running or writer's notebooks — there is a learning curve. Things just don't go right the first time. As a matter of fact, there are implementation dips — after implementing something new or fairly new there will come a time when it doesn't seem to work.

For running, that came at the three-mile mark for me. My mind, not to mention my sleepy feet, could not get past three miles. I could have said, okay. After all, three miles is nothing to sneeze at . . . but if I wanted to lose weight, I'd have to up the mileage. Either I was going to get past this three mile dip and learn to run further in one "run," or I was going to be doomed to running every day. Just for the record, I'm a less is more girl. Less days running more miles is better than running less miles more days for me. So I had to push through.

It's a similar thing with teaching. We try something we know should work. And when it doesn't go as perfectly as it sounds in the books, we stop. We even make up excuses. This doesn't work with the population I work with, my kids just need more grammar worksheets, I don't have time, (add your own common excuse here) ___________.

The first step is recognizing that the dip will come. The second step is having a plan. I'm all battles, good wins when good has a plan. I thought about my own dips in teaching and how I have gotten through them. I started applying these principles to my dips in exercise and weight loss. It's working. So here is my secret for getting through the dips in writing workshop.

First, schedule some time to clarify your thinking about the change — what you hope to accomplish, and how long it will realistically take. We get so congested with curriculum, behavior issues, parent issues, and grading issues, that it is difficult to be a reflective practitioner throughout the school year. Expectations are important and may seem obvious. But, like anything, if it's not written down and specific, they're easy to lose sight of. Setting goals for a change is a perfect entry for a writer's notebook. I try to keep my list to a minimum of three expectations per category, with a maximum of 10. Any more or less than that and it doesn't seem to work for me.

I begin by writing down specific expectations for what I want to happen in general. Here are some things on my list:

- There will be time for writing workshop every day.

- My classroom will have writing materials available to students.

- We will use a notebook to support our writing process.

- There will be books and other resources available to students.

Then my expectation list gets more specific: the kids. What do I expect them to do? If I don't know, then they surely won't know either. Here are some more items on my list:

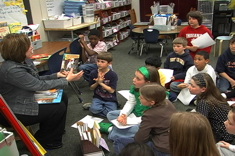

- Students will write each day.

- Students will have their notebooks each day.

- Students will find a favorite author to study and emulate throughout the year.

- Students will edit their own work and be held accountable for things they know.

- Students will use time outside of writing workshop (the other 23 hours of the day) to find writing topics, so that they're ready to go during the workshop time. And my list goes on.

Now I zero in on myself, what do I expect from myself, what can students and parents expect from me? Some ideas from my own list are:

- I will protect writing time each day.

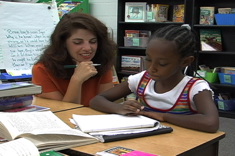

- I will teach students each day what is developmentally and age appropriate.

- I will give timely feedback.

- I will model writing and my own writing process for my students.

Finally, I live in a reality of test data. My yearly evaluation depends on it. So I set expectations or goals for the results I want to see by the end of the year. I do get very specific. It works for me; but it may look different for you. This is also my shortest category of the expectation lists. Not because it's not important, but because I want to keep things manageable.

I have to always remember teaching writing isn't a sprint — a quick unit sometime during the year. It's a marathon — it takes a long time to develop writers. It takes patience and vision. Solidifying in your mind what you expect to happen is the first step in making sure it does happen.