Our seventh-grade curriculum includes several class texts. I love some things about class texts: They are perfect for pulling mentor sentences to teach author’s craft and grammar points that are familiar to all my students, they allow us to engage in common discussions and debates about a piece of literature, and they give us common references to refer to all across the year—kind of like inside jokes for you and your students.

However, they also remove choice of text from the hands of our students.

The first text that seventh graders read is The Breadwinner by Deborah Ellis. This text tells the story of a young Afghani girl and her family surviving during the pre-2001 Taliban rule. We’ve been reading this text for several years, but it is more timely than ever, given the recent events in Afghanistan.

In choosing a class text, our seventh-grade team looked for a text that would be accessible to most readers. Where it is not, we offer support, including, but not limited to, audio of the text. The Breadwinner’s content is serious, about a child’s struggle with an ongoing war, but it is presented in a style that middle schoolers can grapple with. It also provides a window into a world that is unfamiliar to our students, something that we try to make a common theme across our class texts in seventh grade. The unfamiliar vocabulary specific to Afghani culture is supported with a glossary in the back and is mostly easily figured out from context. The length of the text is also appropriate, assuring that the book won’t stretch out for too long to hold the attention of students. Lastly, our students bring some background knowledge with them on the topic of children in war from previously reading A Long Walk to Water by Linda Sue Park.

Despite the thought that goes into choosing our class text, the lack of choice inherent in any class book is a flaw that I try to be cognizant of so I can make adjustments. This year I decided to focus my changes to our regular routine by embedding opportunities for choice across the unit.

Choice of How to Read

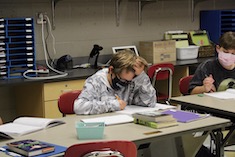

One choice that I give in this unit is how to read the text. On the day we start, I read the first chapter aloud as students look at their own copy of the text, pausing to consider perspective, meet characters, and understand setting. At the end of the chapter, after recapping what we have read, I explain to students that going forward, we won’t be reading together as a whole class, because even though we’re reading the same book, we read in different ways. I hand a small slip of paper to students and explain the three choices that they see:

- read and jot independently with teacher conferences,

- read in a small group with teacher support, or

- read and jot with a partner.

Although I have some ideas in mind about who would benefit from each choice, particularly the small group, I offer only this support at the top of the survey:

Reading a text in class requires you to read in a different way than you may read a book you are reading strictly for pleasure. While I want you to enjoy the book, you will be asked to think critically and analytically. This type of reading will require you to read more slowly and deeply than you would a book that you read for your own pleasure.

Choice of Pacing

At the start of the unit, I give students a pacing calendar that provides, among other things, a projected finish date for chapters and the entire text. Since we will be doing the majority of our reading in class, most students will probably follow the chapter suggestions for each date. However, students can make other choices. Some students like to read ahead, and although we hate to think about students knowing an important part of the plot before their classmates do, it doesn’t seem like a wise practice to have students pause their reading when they are engaged. Instead, I make it clear that even if they read ahead, they have the same requirements for tracking thinking and there is a strict “no spoilers” rule. The pacing calendar also supports students when they’re absent or miss class for some reason.

Choice of How to Track Ideas

I have a love/hate relationship with sticky notes and sometimes need to remind myself that I’m not teaching students how to use sticky notes, but rather how to annotate a text. I have seen students who stop to put sticky notes on every page and students who jot one or two words on a note perhaps five times across a text if no one intervenes. I see a lot of jots that simply copy the words of the text onto the sticky notes. And so I’ll spend a good deal of time in this unit teaching students where it’s worth their time to stop and think what they might actually write to hold on to their thinking.

The act of jotting sticky notes isn’t a choice; I name four sticky notes as the minimum amount of jotting to do in a chapter. However, I give students a choice in how they track their thinking. When I model, I show students two methods. The first is stopping when I notice something significant and jotting right there and then. The second is to note something of importance and leave a blank sticky note to hold the place so I can return to it later, usually at the end of the chapter. Although this isn’t a major choice, I have noticed students who usually write one or two words using the latter method and returning at the end of the chapter to places they’ve marked. We’ll use their jots for discussions as we read and after we read.

I know that some of us may be thinking about the wrong choices that students could make.

- What if they choose to read alone when I know that they could use the support of our small group?

- What if they miss the things that I think are important when they jot?

- What if they read ahead and give away the plot?

- What if they don’t follow the calendar for reading?

- What if it’s “messy”?

Sure, these things could happen. And yes, it can be messy. I’ve had to move desks and adjust plans when partners were out, and sometimes, kids forget to read and have to read in class while we have discussions.

But, do you know what else happened when I tried this and trusted kids enough to give them choice? They started to know themselves better as readers and learners. When my students read in partnerships, they made decisions about whether they would be better off taking turns reading aloud or reading silently before discussing, and they changed their choices when they noticed something wasn’t working for them. When my students chose to read in a small group with me, I was able to gradually release responsibility to them to decide when to stop and jot. In the beginning, the prompts to notice a character acting out of character came from me, but by the end, students were reminding each other to stop because they noticed an object repeating throughout the text. When my students chose to read independently and read ahead, they didn’t give away the plot; instead they returned to the blank sticky notes they had placed to jot ideas and prepare for discussion.

Giving students choice in reading can feel risky, but if we’re going to embrace class texts because of the very real value they can have for our kids, we owe it to them to find ways to return choice to their hands.

Download

Download reading choices survey to use with students.

Download the pacing calendar to offer students choice in the pace they read the assigned text.