Have you ever been part of a school culture where you’ve been asked to consider issues that affect you directly? Maybe it’s about vertical planning, or ways to increase parent participation or creating a mission statement for your school. You spend what seems like hours working in small groups. You record your thinking on large pieces of chart paper and tape them up all over the room. You’re amazed at everyone’s creativity and thoughtfulness, and leave feeling good about your work together.

But no real action is ever taken. At least no action that is reflective of your work together as a faculty. And then you’re asked to do the same kind of thing again and again. You go along with it for a while, but in time you realize that your participation doesn’t really matter.

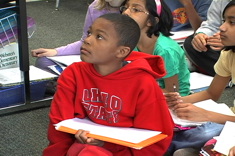

When I invite students to share in the responsibility for making important decisions, I want them to know I expect their responses to be thoughtful ones. I do that by looking right at them the whole time they’re talking, giving a knowing nod or asking for further explanation if I don’t understand.

When I think back to classrooms I love, what strikes me most is an attitude that permeates the very air. Kids seem to breathe in, “I/We can do this,” and breathe out, “Here’s how.”

Kids see themselves and each other as kids with purpose; they see themselves as the kind of kids who can figure things out. They sense that they have the capacity to roll up their sleeves, take action and get things done. And wouldn’t you know — the teacher sees herself, and them, that way too?

We see it in their faces. We witness it in their actions, their work and their words. Creating classroom cultures that promote and support thinking and understanding does sound pretty lofty, doesn’t it? So maybe lofty isn’t the right word after all. Let’s replace it with the word essential.

Our students are learning how to be purposeful and reflective from us all the time.

Ron Ritchhart, in Intellectual Character: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How to Get It says. . .

“One of the things they are learning (from us) is what thinking looks like. In thoughtful classrooms, a disposition toward thinking is always on display. Teachers show their curiosity and interest. They display open mindedness and willingness to consider alternative perspectives. Teachers model their own process of seeking truth and understanding. They show a healthy skepticism and demonstrate what it looks like to be strategic in one’s thinking. They frequently put their own thinking on display and model what it means to be reflective. This demonstration of thinking sets the tone for the classroom, establishing both the expectations for thought and fostering students’ inclination toward thinking.”

This might sound a little lofty, too, but I think you’ll find it’s more attainable than you might think. Because . . .

When we say things like . . .

“Did you guys notice how close Venus was to the moon last night?” Or, “Remember yesterday when Erika brought in that black rock that we thought might be lava? I found a book that has a picture of a rock that looks just like hers–listen to this!” Or “Look at that tree over there by the swings. The leaves are all dry and brown, but they’re still hanging on. Why haven’t they fallen off?”

. . . we’re showing kids our curiosity and interest.

When we say things like . . .

“So you’re thinking the boy let go of his dream at the end of The Sign Painter? What leads you to believe that? Hmmm. I’m going to have to go back and look more closely at that part again. I was thinking he was going to keep following his dream, but now I’m not so sure. Thanks for getting me thinking, Dylan!”

. . . we’re showing our open-mindedness and willingness to consider alternative perspectives.

When we say things like . . .

“Let’s see here. At first I thought this book was about a librarian whose library was a meeting place for all who loved books. But when we read this page, now I’m thinking it’s about so much more. When Alia Mohammed Baker realizes the war is coming to Basra and she asks the governor for permission to move the books to a safer place and he refuses, it says, ‘So Alia takes matters into her own hands. Secretly, she bring books home every night, filling her car late after work’, now I’m thinking The Librarian of Basra is about a woman who loves books so much she’s willing to risk her life to save them.”

. . . we’re modeling our own “process of seeking truth and understanding.”

“Yesterday after school I did some thinking about our discussion of the Underground Railroad. Remember when some of you wondered, “Why did some people not want to escape on the Underground Railroad?” I’m wondering now if maybe it was because they didn’t trust the conductors. Maybe they didn’t believe the conductors were really going to help them to freedom?

. . . we’re modeling what it means to be reflective.

And when we say things like . . .

“Wow. Listen to this. Here it says that the queen ant lays over half a million eggs in her life time. Can that be true? That’s a lot of eggs! I’m going to check some other sources just to make sure–I was thinking it was more like a hundred thousand . . .”

Or, “Caitlin, you said you heard on television that an ant can live in a jar of water for ten days? That seems almost unbelievable, doesn’t it? You think so too? How about seeing if you can do a little research on that, just to make sure they have their facts straight.”

. . . we’re showing kids what it means to have healthy skepticism for the written and spoken word.

We send messages like these in subtle and sometimes not-so-subtle ways. I can simply tell students I’m honored to be their teacher, that I think they’re capable and smart and that I trust them to make wise decisions, but unless I’m specific in my praise and my actions support my words, they might not hold much meaning.

For example, I could say, “That was some smart thinking we just did.” If I leave it at that, they might wonder, “So what was smart about it? What’s she talking about?” But if I follow that statement with something like, “I loved the way you listened to each other and responded back respectfully. Did you notice when Makayla disagreed with Sam, she began with, “Sam — I know what you are saying in ways that took the thinking further” and “Boys and girls, I learned so much from you today. I’m going to have to spend some time after school to sort through it all. Thank you.” and “Let’s work together to figure out how we’ll sort these nonfiction books. How do you think we should begin?” I’m helping students to see themselves as important members of a larger teaching and learning community where everyone’s ideas are valued and respected.