I’ve long heard inspiring stories about schools who adopted a “One Book, One School” experience, exposing all students to a text and then using it to launch conversations and connections.

What would happen, I wondered, if we had an all-school writing project? Could it work, even if some of our students were just learning to write and others were ready for multi-page writing? How could I lead such a big project? I worried about big things: how to get staff to embrace the project; how to have all students create high-quality writing; and how to share the writing with our community in a tangible, authentic, inclusive way.

For years, I’ve been enamored with Larry Smith’s Six-Word Memoir project. I’ve read all the books, written a pile of my own six-word memoirs, and sometimes do my best reflecting in six-word increments. Six-word memoirs are a masterful way to tell a story. If you’re not yet familiar with this concept, you should read the books or visit his site to join a community of storytellers. The memoirs will move you and shake you. They’ll make you laugh and weep. I read them often, only a handful at a time, and find it to be an excellent way to imagine a full story—especially when I take the time to really think about the author’s voice, purpose, and experience. I can create and complete the mystery that lives beyond the six words. In a lot of ways, six-word memoirs open up acres of imagination, inserting the reader in the story and letting it go where it needs to go.

Six-word memoirs seemed to be the perfect way to have our students be part of an all-school writing project. Here’s how it happened.

1. Start with a committee of believers. I put out an all-call to teachers, welcoming anyone who wanted to be involved in our project. Many teachers answered the call, and each one was passionate about student writers. Each believed in finding ways to celebrate each child’s voice. They were all eager to partner up to plan, pilot, and implement our project.

2. Develop goals, a timeline, and a communication plan. In our first few meetings, we solidified our purpose and developed goals for our project. Then we developed a series of steps, first settling on a timeline—a month to pilot the project on a small scale in a few classrooms; a month for all teachers in the school to teach the concept, practice, and support students in writing their memoir; and a month to share, celebrate, and publish the student work.

3. Provide mentor texts. I purchased multiple copies of Six-Word Memoir books and made them available to the committee. They read the books and then developed instructional plans that aligned with their standards. They met informally to share tips and tweak their plan.

If you provide copies of these books to teachers, they should not share them with students carte blanche—some of the memoirs in the published collections are not appropriate for young learners.

4. Roll out to staff. At a staff meeting, we shared a summary of our process and goals, and then provided them with scripted plans they could follow. We were careful to clarify that the plans could be implemented as scripted or adjusted in any way each teacher thought best—we wanted the project to belong to each of them and each student in the school.

5. Capture. We created a Google Forms sheet with tabs for all teachers to enter the student work. Again, we asked teachers to do this in a way best suited to them; some chose to type the memoirs in themselves (as in the younger grades), and others had students enter their memoir into our Google Form. Having all the memoirs in one location allowed us to easily download the writing into one document for publishing.

6. Publish. Using one single Word document, we compiled all the memoirs from every student (taking care to check for spelling and appropriateness) and crediting each memoir with the child’s first name. We collected small self-portraits, doodles, and designs created by students and interspersed them all over the final copy, and then sent it off to an affordable printer. Every child received their own copy—700 six-word memoirs written by their friends and classmates.

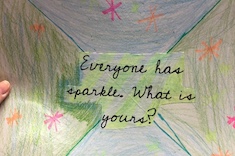

7. Display. While we were working on the publishing part of our project, teachers were displaying their memoirs in ways they thought were best for their students. Some teachers had their students make artwork out of their memoirs; others made displays for hallway or classroom viewing. When we saw lovely displays that captured the myriad student voices, we’d include tips in the weekly staff email update—“Make sure you take a look at the memoirs outside rooms 136, 146, and 212!” Teachers took their classes to visit other displays throughout the school, and individual students often stopped to gaze at displays as they made their way through the hallways.

8. Perform. As we reached the end of our all-school writing project, I selected several memoirs to be “performed” at a school assembly. Students were given a moment at the microphone to read their memoir. The text-to-voice readings captured all of our students’ attention and helped them build connections to one another as peers, schoolmates, and writers.

Why It Worked

The project was a success for many reasons.

We used a common language. Every single person in the building had learned about the six-word memoir, and every single person had read or seen the work of others. Making it part of our everyday conversation connected us as writers using a common language.

It was so simple. Our project wasn’t ambiguous or difficult to implement. Had we said, “Everyone should write a narrative,” or, “Write an opinion piece,” teachers would have had an interpretation and management task on their hands—trying to define and “police” the type of work handed in.

It was short—but meaningful. Six words. That’s all. Expectations were clear and manageable, but allowed for depth and rich thinking.

It helped us get to know our students on a deeper level. One fourth-grade teacher had her students write multiple memoirs and select the one that best represented their true self for turn-in. On the designated day, one sweet girl, typically quiet and guarded in personality, turned in this: I do not have a dad.

When she read the student’s memoir, the teacher’s relationship with the student instantly deepened, because she recognized the emotional risk the student had taken, which evoked trust and empathy that might otherwise have been missed. There were literally hundreds of examples of how teachers found new ways to connect with the young writers in their classrooms.

It built excitement with the possibilities. In the end, no one could deny the power behind an all-school writing project. Even the reluctant teachers got on board because they felt it . . . and wanted to do it again.

Anyone considering an all-school writing project can find comfort in knowing the large-scale project was actually relatively easily to manage. With committee leadership, strong communication, and a clear goal, your students can come together as writers, creating their stories and sharing them with the world around them.

For us, it took just six words.

(If you would like to view a presentation I created on the project in PDF format, click here.)