No digital platform is an effective instructional tool unless I am thoughtful about how I use it to give and receive feedback. As a middle school language arts teacher, I have learned a few lessons about feedback through using digital tools in my instruction.

Receiving Feedback Is a Skill

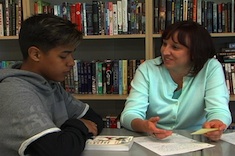

After years of handing back student drafts peppered with teacherly guidance, I learned the value of face-to-face conferences. If you have ever taught in a writing workshop, it is likely you know firsthand the value of pulling up a chair alongside a student to confer about a piece of writing. There is a special sort of magic in speaking to students writer to writer.

The experience of conferring has helped move the comments I make on drafts of student writing from teacherly guidance to writerly support. Often, I find my comments come in the form of a question rather than a correction or suggestion. However, unlike in face-to-face conferences, written comments are easy to overlook or even ignore.

When I first noticed students were failing to react to comments I would type in their Google Docs, I was frustrated. It takes a serious commitment of time to read and thoughtfully respond to student drafts. It would be much easier to mark a box on a rubric than to engage in written dialogue with a writer. Why did they not find the comments to be worth their time when I was spending so much time on them?

Immediately I remembered a teacher I worked with when I first started teaching. In a meeting one day, she gleefully shared how she used the Track Changes feature in Microsoft Word to “catch” students not responding to her feedback. The process of shaming students had been streamlined by the digital feature.

Thinking back on this encounter and my immediate negative reaction to her approach helped me recognize my own beliefs about the purpose of feedback and digital tools. I was sure my goal in giving students thoughtful feedback was to have them benefit as writers. Rather than remain frustrated, I wondered if it was possible that students did not understand how to use my comments as writers.

By taking an investigative approach to understanding why student writers were ignoring comments in Google Docs, I learned that some students did not even realize the comments were there. Because our students do not have email accounts, they had no way of seeing a notification. Rather, they had to have a reason to reopen the document to even see that the comments existed. Who knew teaching students to access feedback could solve half the problem?

Students also sheepishly shared that they would sometimes mark comments as resolved because they weren’t sure where or how to answer the guiding questions I would ask. For example, I might write something like, “What did you mean here?” or “How could you show readers what you were thinking or feeling?” Students had no problem making sense of such questions during face-to-face conferences where they could propose an answer, I would respond, and we would immediately connect that to the action steps they could take as a writer. In the digital context, I was expecting students to make the leap to action steps without the conversation, but students still felt the need to have the conversation first. Once they were given permission to act on their own without additional input from me, more students began using the questions to drive revisions.

Now, each time we use a new digital tool in which I provide feedback to students, I take time to teach them how to access and make use of my feedback.

Beware of Grades

Recently I took some online college courses to earn an additional endorsement. In my experience as a digital student, I recognized an unsettling mindset about grades. Each time I would log in to check my grades, I had one purpose in mind: to see if I was doing all right. Grades became a litmus test indicating whether I was okay or not okay.

It sounds logical at first—grades are meant to be an indication of whether student performance is on track. However, the aftereffect of that mindset was what concerned me. If I checked a grade and it was perfect, I read the comments that accompanied it and felt validated. I continued doing what I was doing as a student—even if it meant I was not putting forth my best effort. If a grade was less than perfect, and I had put forth my best effort, I read the instructor’s comments for the sole purpose of rolling my eyes in response. I became less motivated to work hard because I felt like it wouldn’t be good enough anyway.

Since reflecting on my own experience, I have noticed a similar pattern of behavior in my students. The students who do really well in our online nonfiction reading program are highly motivated to keep up their scores. Sometimes this results in their taking far longer than necessary (maybe far longer than is even healthy) to complete online quizzes for fear of missing a point. On the other hand, the students who consistently struggle tend to avoid engaging with the program. They are the students who have other tabs open while working, who do not look back to the text to double-check anything, or who jump straight to the quiz and skip the reading.

Although I cannot change the scoring component of the online system our district employs, I can provide feedback in other forms, like questions and comments, while students are still in the process of working through the text, to demonstrate that I value the reading process more than the outcome as measured by the online quiz.

Student Feedback Matters Most to Me

A close friend of mine is a yoga instructor. Recently we spoke about her reluctance to add online yoga courses to her repertoire. She described how difficult it is for her stand far enough away from her computer to demonstrate poses while still viewing her students well enough to respond to their movements. In a face-to-face class she might read their body language and provide a gentle nudge to relax their shoulders or lift their toes off the mat. During one online session, she persuaded her son to follow along in person to serve as a cue to prompt her to give more specific instructions when needed.

Listening to her speak, I thought about how reliant I am on feedback from students. I have even caught myself relying on certain emotive students to whom I look in each class for confirmation of my clarity. I am constantly reading eye contact, posture, facial expressions, and movements to gain information about student needs. In a digital world, many of those tools are removed from my toolbox.

Sometimes, I am able to use digital platforms like Flipgrid, Zoom, or Padlet that allow me to see students. However, eye contact, posture, facial expressions, and movements are no longer indicators of engagement or understanding the way they were in the classroom. A student looking down or off-screen while recording a Flipgrid video may be referring to notes rather than being distracted. Slouched posture on Zoom may be an indication of discomfort with the platform more than a disinterest in the meeting.

I have to be more explicit about eliciting feedback from students when using digital tools to connect. Sometimes this takes the form of requesting an immediate response in the chat box during a Zoom meeting. Other times, it means I add a reflective question at the end of a Flipgrid prompt or even add a link to a Google Form survey in Padlet.

These three ideas about feedback are a small piece of all the lessons digital tools have to offer. I am looking forward to continuing to learn from my students as we engage with more digital tools this school year.