Kelly Gallagher, the best-selling author of Readicide and Reading Reasons

, talks about the importance of teachers modeling writing for students. You can read more about Kelly’s work at his website: http://kellygallagher.org/

A full transcript is available below the player.

Franki Sibberson: Kelly, your upcoming book is about writing models. Can you tell us a little bit about the idea behind that book?

Kelly Gallagher: Yeah. I have a book coming out in October. It’s titled Write Like This, and the basic premise of the book is that the best way to learn something is you stand next to somebody who knows how to do it and you carefully watch how that person does it. If I’m going to teach a kid how to shoot a basketball, I’m not going to just draw it on a piece of paper, or I’m not just going to shout it across the gym floor. I’m going to have the kid come over, stand next to me, watch how I hold the ball in my hands, how I put it up on my fingertips, and I’m going to shoot two or three or four, and then I’m going to have the kid shoot two, three or four.

That’s how we learn. I mean, that’s how I learned how to wait tables. When I was in college I was an executive table technician, and the way I learned that was I followed somebody around who knew how to wait on tables. This apprenticeship model, I think is really the best way to learn. A lot of the studies that have recently come out have indicated that kids need models. When you have a model you need to do three things. You need to read the model, you need to study the model, but most importantly, you need to emulate the model.

In Write Like This, what I am sharing in that book is what I’ve done in my own high school classroom – in fact, I just did it an hour ago in my fifth period class – is if I want my kids to write something, I go first. I get up and I stand in front of them and some days I write really well, some days it doesn’t flow at all, but I think it’s really important for kids to see the best writer in the room, the teacher, stand up and wrestle with it, this mysterious thing that we call writing, and showing the kids the only reason I’m a better writer than they are is because I’ve done it a lot more. It’s not because I’m smarter. It’s because I’m more experienced. And so if you want to be the best mechanic, you go stand next to the best mechanic and watch how he fixes the car, or she fixes the car.

So it’s this premise of model, model, model that I’m really bringing into my classroom, and I’ve really seen it elevate my own students’ writing. I would add that I’m not so egotistical that I think that the only model they need to see is my writing. I also bring in real-world writers as well. So if I want my kids to write a really good persuasive essay, I’ll go out in the real world and find a really good persuasive essay, and we’ll come in and we’ll read it and we’ll study it. When I say study it, what I really mean is sort of moving away from asking kids — when they read a passage, we usually ask, “Okay, what does it say?”

I go through that, but I try to get through that quickly so I can get to what I think is the more important question and that is, “How is it said? When you look at this model piece of writing, what did the writer do here, and what did the writer do there? What do we notice at the conclusion here? What do we notice over here?” And really studying the piece of writing as a way to get kids now to enter that particular discourse on their own. So yeah, I want them to stand next to me but I also want them to stand next to Rick Reilly in ESPN Magazine or Leonard Pitts, a columnist in Florida, or Anna Quindlen or George Will or anybody whom I believe to be a good writer and whom I believe my kids would be able to shadow and emulate.

Franki Sibberson: So when you’re looking for models other than yourself, what are you looking for in writing models, to share with your students?

Kelly Gallagher: Usually it’s driven by the discourse that I’m having my kids wrestle with. For example, in Write Like This I really focus each chapter on a particular discourse and I tried to focus on those areas of writing that I hope my kids will be doing 10, 20, 30 years from now, not just real strict, kind of fake school writing, but the kind of discourses that, again, I hope that they adopt as life-long writers. One chapter I’m having them do reflection, or one chapter they’re exploring their thinking through writing. One chapter they’re explaining their thinking, or they’re taking a stand, or they’re evaluating and judging, or they’re proposing solutions to things.

So if I want my kids to take a stand in a piece of writing, then I will go out and look for a writer who does a good job of that particular discourse. I don’t really start with the skills in mind as much as I’m starting the particular kind of writing I want my kids to emulate.

Franki Sibberson: How have you seen these models really help your students? Have you seen a big transfer?

Kelly Gallagher: Well, absolutely, and what’s interesting about it is I’ve been told – and I have some low students, too. I teach four periods this year of ninth grade, and from those four classes I’m taking the lowest kids, and I get them again for a second hour because I believe very strongly that the only way kids who are behind grade level in reading and writing are going to catch up is if they have twice as much reading and writing as everybody else on the campus. Well, when I formed this class I was told, “Well, those kids can’t write, and so you better give them formulaic writing. You better teach them how to write a five-paragraph essay, and this paragraph has to have two of these kinds of sentences and three of those kinds of sentences.”

I was told by more than one veteran teacher, “That’s the only way. Those kids need structure. If they don’t have structure they can’t write.” I couldn’t, based on the last year or two that I’ve been using my classroom as a laboratory, I couldn’t disagree more. The kids don’t need a formula. They need an actual piece of writing that’s good. And if the teacher leads a meaningful discussion, kids can see that, hey, the writer started this essay with a question; I can do that. Or, the kids can see that this writer is using intentional repetition. The kids can go practice that.

Roger Ebert, writing movie reviews – and he’s still writing today – he’s never written a review that said, “Harry Potter is my favorite movie and in this review I’m going to tell you three reasons why.” What he does is he starts with humor, or he starts with sarcasm, or he starts with a question, or he starts with a statistic or an unusual statement. So it’s getting kids to notice those things, and then, of course, me writing along side them I think is really, really valuable in helping kids write like real writers do.

Franki Sibberson: So that combination. You talked about you serving as a writing model for your students and you being first when you do something with writing. What advice do you have for teachers who really aren’t confident or don’t see themselves as writers?

Kelly Gallagher: Get over it. I mean, really, get over it. I get this from teachers a lot and I totally understand because my kids think that I’m Superman, because the only writing that I’ve ever done, that I’ve shown them, was writing that had polished and cleaned up before I brought it into the class. But that’s not how real writers write in the real world, and what I’m suggesting is – in fact, as I mentioned earlier, there are days I get up in front of my kids and I can hardly write at all, and I think those days where it’s not really flowing is actually as important for my kids to see than those days when I just get up and everything comes out beautifully.

I mean, we run under the premise, in my classroom, that every first draft is crummy. I walk around my classroom and I actually say, when first drafts are due, “Please hand me your crummy first drafts.” I use those exact words in my classroom and the kids kind of laugh, and I’ll say, “You know what? I’m sorry. I haven’t read your papers yet, so how do I know they’re crummy?” And my kids, in choral response, will say, “Because they’re first drafts.” I think a lot of times we give kids the wrong idea about writing, because we don’t write in front of them, and we don’t struggle in front of them. I mean, think about this. How often do kids see the teacher in the classroom struggle? I think it’s really important for the kids in the classroom to see the teacher struggle, because they have a false impression.

They think I just crink my neck a couple times, roll up my sleeves, and boom, it just comes out. And what I want to suggest is that it’s time for the great Oz to come out from behind the curtain and to get in front of that classroom, and to show the kids you have good writing days and you have bad writing days. And you know what? I think the idea that you have to have a good writing day in front of your kids is a fallacy. And you don’t even have to be a super writer as a teacher. You’re going to be a little bit better writer than your kids, but again, to me it’s not the writing. It’s the rewriting.

Today I drafted in front of my kids – well, you know, I don’t say this at the beginning of the year because it’s not true. At the beginning of the year I’m trying to get every one of my kids to write, even those who do not like to write. But once I get them all writing, I say, “Well, anybody can write. The hard part is the rewrite. Revision is where it’s at.” And so I think that polishing of the paper and showing your kids, “Look, even the teacher wrote something that needs to be polished,” is really important.

I co-directed a writing project site for a couple of years, and we would leave at the end of every summer with 20 strategies or 30 strategies that we were going to try in our classrooms when we went back in the fall, and this may be different for other teachers but I can say for me personally, I don’t think there’s a single writing strategy that I have brought into my classroom that was more effective than adopting an I-go-you-go rhythm to the classroom.

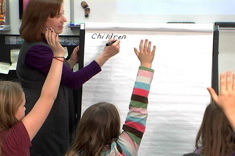

You know, what’s really interesting to me is, in my view, it is probably the most effective, while at the same time least utilized strategy, at least in secondary schools. I think early elementary teachers get this. They write in front of their kids all the time. But again, I think as kids get older, teachers assume kids know how to write, and I think it’s a dangerous assumption. I don’t think we ever finish learning how to write. We just learn how to write better.

Franki Sibberson: Yeah. I don’t think it ever gets easier either. So you’re really not pretend writing up there. You haven’t thought about it; you haven’t drafted it out. You’re really modeling the whole process?

Kelly Gallagher: I try. Sometimes, for example, I might look at a model with the kids and then I might write an intro for Period 1. And then I might hold onto that one. Period 2 comes in, I might show them the one I wrote for Period 1 and then I might try a different hooking strategy in Period 2. And then Period 3 comes in, and I repeat the process. So by the end of the day I’ve written four or five different introductions to the same essay. Or I might write the introduction or the beginning of the essay first period. I might share that with second and third period. I’ll write the body in second or third period and share that with the classes at the end of the day.

So I might take an entire day to write one essay. What I do not do is I do not write a complete essay first period, a different complete essay second period. I can’t write five essays a day. I would drop dead by Halloween. And the other thing is, I don’t model for more than seven or eight minutes in front of my kids.

Franki Sibberson: That’s quick.

Kelly Gallagher: It’s brief. Sometimes I ask for them to chime in and help me. I don’t like this. Should I do it this way? How many of you like it this way? How many of you like it that way? But they need to see the creation process. They need to see how it happens.

Franki Sibberson: One last question. You talked about you being warned that these kids in your class needed formulaic, kind of controlled writing and you found that not to be true. So when teachers and administrators who are nervous about writing tests and all of that, what advice do you have about the time that they have with their kids, especially secondary?

Kelly Gallagher: Well, a lot of that comes down to, one of the things I try to teach my kids right away is when you sit down to write you’ve got to know your audience and purpose. I mean, your audience drives how you write it. I have my kids write this on the board: “Hi. How are you?” and then I have them rewrite it. How would you write it if you were saying it to your grandmother? How would you write it if you were saying it to your girlfriend? How would you say it or write it if you were in a job interview? How would you say it if you were at lunch and you were talking to your buddies and there were no adults within earshot? And what happens is the kids write it differently every time, because the audience determines how it should be written.

So if your audience is a state test reader or an AP exam reader, then I think there is some value in teaching kids how to write to that audience. In that situation you want a very brief but clear thesis statement, and you might write a four- or five-paragraph essay, boom, boom, boom, and you’re out. So I think there’s room in the curriculum for teaching kids how to do that. My concern is that when that becomes the only way kids are taught how to write – and as I said before, Roger Ebert doesn’t write that way; Thomas Friedman doesn’t write that way; I don’t know anybody who writes that way out of a school testing situation.

And again, my students’ writing scores are pretty good, and I spend zero time teaching them formulaic approaches. I do do a little bit of how to approach a timed writing or on-demand writing, because I think the purpose of that is a little different, and I think the cognitive processes that are utilized when somebody says “On your mark, get set, you go. You have 40 minutes” is a little bit different than if you have a week to take it through the entire writing process. So the kinds of approaches my kids have to the writing, I think is dictated by them recognizing what’s the purpose of this and who’s the audience.