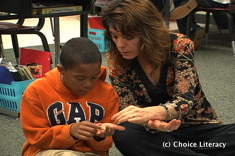

"Do you know what I've been thinking and reading about?" asked Will as we settled into an out-of-the-way spot in my grades 3-4 multiage classroom. It was time for reading workshop and the room was quietly buzzing as readers gathered books and other resources, settled into their places, and the hum of engaged learners slowly crept across the room. Will's green eyes were sparkling with excitement as we began our reading conference.

"What's on your mind?" I asked, sensing that he had big things to tell me.

"I'm studying the creek for my micro-habitat study, right?" he said, referring to our ongoing science unit — "Reading and Writing Like a Scientist." "Remember how I found the raccoon tracks by the creek? Since then I've been reading a lot about raccoons."

He showed me two books and an article printed from a website.

"So what's your plan for today?"

"I want to use my time today to answer a few of my wonder questions about raccoons. Since raccoons show up to find food in the creek, I think I need to know more about raccoons if I'm going to really get how the creek life works as a system. Don't you think that's a good idea?"

"Tell me more," I prompted, starting to jot notes in my conference notebook. "Show me what you are thinking about."

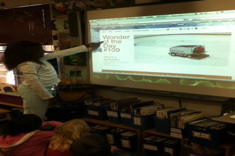

I was eager to see what Will had to share. During the first weeks of this science unit, my students were anxious to explore and learn in our outdoor learning lab. I took advantage of their enthusiasm, planning a series of explorations lessons that captured their Wonder Questions. As the children explored the outdoor lab, I recorded the group's questions and "wonders" in my notebook. Following the exploration period that lasted several days, students were then asked to thoroughly explore one micro-habitat and generate their own wonder questions about the micro-habitat.

After posting students' micro-habitat questions on our Wonder Board, students worked with a partner and selected at least three of their wonder questions to answer. It was important for students to continue their outside observations while learning how to use a variety of books and websites to answer their questions. Writing like a scientist was inseparable from reading like a scientist. During science time, I presented a critical set of minilessons on using research organizers, like two- and three-column charts with headings, webs, and other info-graphics for gathering dash notes. I wanted to see how our science work would affect students' thinking during reading workshop.

Wonder Questions Lead to Independent Learners

Wonder Questions are a critical part of my students' nonfiction reading. Debbie Miller has written and talked extensively about these questions in Reading with Meaning. Rooted in a respect for each individual's learning and interests, Wonder Questions honor the fact that each person views the world differently. Given time and support to identify interests and the freedom to consider "What do I want to learn?" children naturally understand how to create authentic, thought provoking questions. Wonder Questions help a teacher consider that fragile balance of support — knowing when kids need us, and letting them discover when they can move ahead in their learning without us.

Will opened his notebook to a tabbed page labeled raccoons. He showed me a list of Wonder Questions he'd developed and recorded on a two-column table across two pages in his notebook. One column listed his questions, and the other column provided a place for his future dash notes once he begins his research.

"You have big plans," I said, as I proceeded to read aloud his questions about raccoons.

Why is the raccoon usually at the top of the food chain and not eaten by predators? Do they taste bad?

"What made you think about this?" I asked.

"Well, just look at them . . . for some reason they don't look tasty and they eat odd things, so maybe they just taste weird. Or are they just good at keeping themselves safe?" he said with a very earnest look.

"I don't know . . ." I answered, now wondering about the same question.

Raccoons' front paws are useful for catching and eating food. Why are the back paws shaped differently? How do they help the raccoon?

"I never thought about this before when considering raccoons." I looked at a picture of a raccoon and a diagram of raccoon tracks Will had marked in a book.

He was puzzled. "Well, our hands are different from our feet, so doesn't that seem like a good question to ask about another animal?"

"Absolutely," I answered while I moved to his next question.

What creatures in the soil will break down the raccoon's dead body so it rots back into the soil?

"I think I just need to know this," said Will. "I really want to understand the last part of the food chain and the last part of the raccoon's life. I know some about vultures . . . And it's weird. Now that I've been thinking about raccoons, I see so many dead raccoons on the roads. My mom even lets me move dead raccoons to the ditch when we see a dead one when we're driving . . . ever since I started studying raccoons I notice them."

"Really!?" I commented making a note about his serious intentions about understanding food chains.

"Don't worry — we keep a box of those plastic gloves in the car so I'm not touching the dead body . . . and I only move them when cars aren't coming . . ."

"Aren't moms great?" I smiled, adding a side-note to email this amazing mom who was supporting her child's fascination with animals to the point that she took the time to let him examine "road-kill" whenever they came across it.

And so unfolds our conference. I learned so much about Will as a reader, thinker, and person during those few minutes of our conference. I discovered what he was thinking about beyond reading workshop. I saw how our science work was influencing Will's ability to identify his interests. He demonstrated how he had taken charge of his learning and reading by drafting such thought-provoking Wonder Questions.

"I think we can try to identify the living and non-living things in the soil that will help decompose the raccoon some day when it dies. We should talk to Dr. Languis about this and get you two together . . . he knows so much about the role of soil and decomposition because he is such a composting expert. He might know some things about what helps decomposing animals after they die."

I wrote a reminder note on a post-it to email a retired professor who works with our school in our outdoor learning lab to see if he could meet with Will during the coming week to discuss decomposition.

"I better write that word down," said Will, as he wrote decomposing at the top of the page. "That is a better word than rotting."

"Are you ready to get back to work?" I asked, already knowing Will's answer. "You can just keep this spot . . . I'll move along to my next conference now, okay?"

"Uh-huh" he mumbled, already flipping through his book to begin his work, almost unaware that I was leaving him (for now).

My time with Will strengthened my confidence in my decision to introduce Wonder Questions during the first weeks of reading workshop. Through minilessons, guided experiences, and then opportunities to try Wonder Questions in a supportive workshop community, Will's conference comments and reading plans documented how he had adopted a vital learning strategy that could support him as a learner now and in the future. I reconsidered his opening words today:

"Do you know what I've been thinking and reading about?"

Now my conference notes would bring mental snapshots of Will discovering raccoon tracks by our school's creek, his carefully crafted questions, and how he moves a dead raccoon to a safer place to decompose into the soil. The word wonder sanctifies the art and science of learning, reminding me to begin each conference with a quiet reverence for my students' thinking. Wonder brings respect, energy, and determination to our work. How might your students answer this question: What have you been reading and thinking about?