A text that becomes a part of the student long after he reads it and leads him to think and act differently as a result of the text becomes part of his lineage.

Alfred Tatum

Ever since I heard Alfred Tatum speak about the textual lineage of adolescents, I have been interested in the potential of self-selected books to shape student identities. It is a wildly fulfilling and humbling responsibility to play a role in supporting student growth by helping build textual lineages that affect who they are and who they will become.

Last year, as a means of reflecting on a year of building textual lineages, I asked students to arrange the books they had read throughout the year in a meaningful way. They started by creating and sharing a Google Doc containing images of book covers for each of the books they had completed or anticipated completing before the end of the school year. It was essential that they also typed their names on each page of the document. I printed the docs in color, and the names made it simple to distribute them to their creators.

Before students began cutting out the images, we brainstormed about possibilities for arranging the covers in a way that would communicate something about them as a reader. I pointed to a bulletin board where I had posted book covers as I finished books throughout the school year.

I asked students if they could come up with some more thoughtful ways to organize the books than simply putting them in the order in which they were read. Students suggested things like grouping the books by genre or topic, ranking them from worst to best, and arranging them in order of difficulty. I made sure students understood they did not have to feel limited by these suggestions, but should keep in mind that the point was to demonstrate who they are as readers through the arrangement.

Although I had done a similar project in the past, I had always forced students into arranging books into a reading ladder or roller coaster to demonstrate the variety of rigor they experienced as readers. The simple shift to giving students choice in how they arranged the book covers led to results that not only showcased their readerly identities, but also pushed me to reflect as a teacher. Looking at the finished products, I was sobered by the realization that I have a serious responsibility to know my students, to know literature, and to provide students with access to literature.

Know Your Students

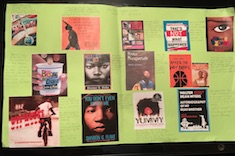

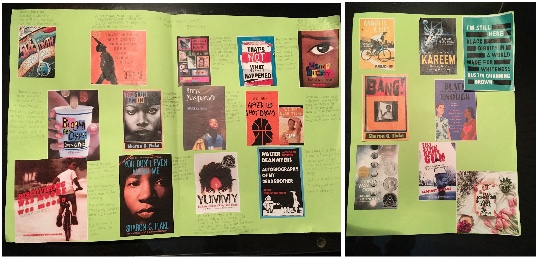

Above is an image of Journey’s book cover reflection. She chose to arrange her titles by “Social Awareness Issues.” She labeled the organization within this topic as “Least to Greatest.”

Looking at her two-page reflection, I am reminded of the first time I met Journey. Although she was not my language arts student until eighth grade, I met her as a seventh grader when our school librarian reached out to me. Knowing Journey was seeking books similar to The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, the librarian asked for help making recommendations since Journey had already devoured all of her suggestions. The first time I was introduced to Journey was when I lent her my copy of How It Went Down by Kekla Magoon. After that, I gave her All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes.

When she was an eighth grader, I got to know Journey even better. I learned she has family in Chicago and a cousin she looks up to who attends Urban Prep Academy. I learned she has an uncle who puts together conferences addressing social issues and race. I learned she is driven to continuously learn and grow, but is not always interested in what school has to offer. I learned she could often be caught sneaking reading time instead of paying attention to instruction or classwork. I learned she is kind to classmates, especially those who could use some extra attention, and she is a leader among her peers.

I learned these things from observing Journey in class, from listening to her, and from interacting with her as she arrived to class each day. If I had not been present enough to gather all this information about Journey, it would not have been so easy to feed her hunger for books relevant to her life, to her world. Journey’s passion for social justice is shaped by her family and life experiences. She is interested in books that raise social awareness, that reflect her views, and that help her consider other ways of seeing her world. Knowing her data was simply not enough to help me provide texts that would have a lasting effect on her identity.

Know Literature

Knowing what Journey was looking for as a reader was also not enough. I also had to know adolescent and young adult literature well enough to make recommendations.

Looking at Journey’s book cover reflection, you can see she reads a wide variety of texts:

Novels in Verse

Rebound by Kwame Alexander

Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds

Bronx Masquerade by Nikki Grimes (mix of prose and poetry)

Short Story Anthologies

Who Am I Without Him? A Collection of Stories About Girls and the Boys in Their Lives by Sharon Flake

You Don’t Even Know Me: Stories and Poems About Boys by Sharon Flake

Black Enough: Stories of Being Young and Black in America edited by Ibi Zoboi

Nonfiction

Discovering Wes Moore by Wes Moore

Becoming Kareem: Growing Up On and Off the Court by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Fist, Stick, Knife, Gun: A Personal History of Violence in America by Geoffrey Canada

I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness by Austin Channing Brown

Graphic Novels

Yummy: The Last Days of a Southside Shorty by G. Neri

The remaining 10 books are all contemporary realistic fiction.

I have read all the books pictured on her reflection except three. The three I haven’t read myself I have made it my business to know about. My students are dependent on and limited by my knowledge of literature to help them connect with meaningful, relevant texts.

Provide Access

The fact that our school librarian reached out to me for help connecting Journey to books when she was in eighth grade is evidence that access to the books she needed was not readily available. I have to make building my classroom library a priority if I hope to affect lives through literature.

Acquiring books for my classroom library takes a commitment to finding solutions. When I am unable to purchase books myself, I write grants, appeal to administration, and connect with our public library’s teen librarian to get the right books into my students’ hands and hearts.

Multiple times, I made book purchases based on a request from Journey. She was such a leader that I knew an investment based on her recommendation would pay off because it would be read by not only her, but any peer to whom she suggested it. One time, I walked past her desk to find her on a book shopping website reading a preview of I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness by Austin Channing Brown. She read the section of the book that was previewable and shoved her Chromebook toward her friend, who immediately began reading. Before walking away, I had written down the title to explore before ultimately purchasing it for our classroom library. The book even came home with me for the summer based on Journey’s recommendation. I read it, too.

If I grow my classroom library based only on my own recommendations, I will miss out on the authentic diversity created when I listen to what students want.

Although my students completed book cover reflections at the end of the school year, I think they would make effective bookends to a year of reading. Students could begin the year by sharing books that have affected them so far and end the year by incorporating new titles in a final arrangement. I believe giving students time to reflect on their reading lives and identities not only helps them record textual lineages, but helps to create them.