Parents want what is best for their children, but often lack understanding of the importance of matching texts to readers. Teachers come to us seeking advice about how to help parents understand this concept. Many parents advocate for their children by trying to convince teachers that they are not giving their children texts that are challenging enough. As teachers, we know that students need “enormous quantities of successful reading to become independent proficient readers. It is the high accuracy, fluent, and easily comprehended reading that provides the opportunities to integrate complex skills and strategies into an automatic, independent reading process.” (Allingon, 2002) How do we help parents understand our decisions around text levels and give them an avenue to advocate for the reading lives of their children?

We find that equipping parents with current research, encouraging them to think about long-term dispositions for their children, and sharing some good analogies about everyday life has helped us explain to parents that text difficulty is not how we measure or develop effective readers.

Share Current Research with Parents: School is Not What it Used to Be

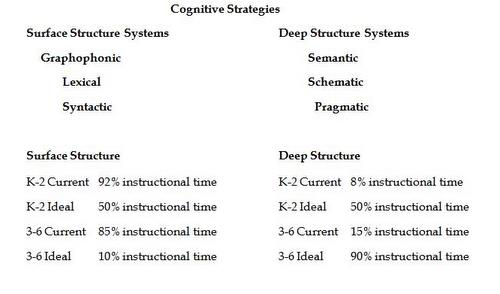

We want children to experience a balance of text. In today’s information technology driven world, we no longer are preparing our children to be “fact finders.” We need a workforce of thinkers — people who can synthesize information from various sources to create new ideas. Rumelhart’s research (see charts below) supports this notion and encourages teachers to begin to teach the deep structures of reading at an earlier age (2004). We need to create classrooms that get kids talking and thinking about texts with each other.

The standards that children are being held to are much higher today, but developmentally children have not changed. Using text levels as one tool for matching students to books can help students access higher order thinking strategies. If we want them to use more deep structures then we must at times make the surface structure easier. Allowing children to focus less on surface structures gives them more cognitive capacity to think and talk deeply around text. Parents need to understand that we know their children can read difficult books, but we are not only asking them to read the words of the book. We need kids to be thinking deeply about theme, character development, author intention, and symbolism. We choose books that support students in doing this type of thinking. Parents need to understand what we are trying to teach and how students are challenged with various types of texts. Once they hear that we know their children as readers and we are teaching them with intention, we find that they support our choices for their children and worry less about “challenging their children with harder texts.”

Long Term Dispositions: Raising Life-Long Learners

We often begin parent outreach sessions by asking parents to reflect on themselves as readers and to think about what they hope for their children twenty years from now. These two questions always spark wonderful conversations around dispositions.

We might also ask, “What is currently on your nightstand?” We then have family members turn and talk to a partner about this bedside reading. Parents look at us in horror when we do this during workshops. They are often embarrassed to admit that there is nothing on their nightstand, or that what is there may not be considered high quality literature in our society. It opens the door to a conversation about real readers, and how often we are holding our children accountable to much higher standards as readers than we hold ourselves.

Our nightstands have cookbooks, professional books, children’s literature, our current book club book, J. Jill catalogues and People magazine. (Yes, we like to shop and find out what is going on with Brad and Angelina.) Real readers read a variety of texts — easy, difficult, long, short, fun, and practical. Real readers do not walk into Barnes and Noble and ask for the longest, most difficult book. Real readers do not only read what someone else wants them to read. And most important, real readers have to find time and rituals to make reading a part of their lives.

When we do this exercise with parents, they begin to think about why they do or do not read. Many adults read for work, or only read newspapers and magazines. Many admit they are too tired or busy to read for pleasure so they only read on vacations. Avid readers talk about why they read and how this passion began. We encourage parents to share their reading lives with their children. Parents need to talk with their children about why they read and when they read. Finding rituals, special spots, and times for reading are essential for every family. Kids need to have authors they love, topics they are passionate about, and series for which they eagerly await the next book to be published.

As teachers, we need to encourage parents to be “caught” reading by their children, to continue reading to their children even when they can read themselves, and to share their habits as readers. When do they read? How do they find books that are interesting to them? Where do they read? How do they read a book that is not interesting to them? We also need to remind parents that we as readers do not always come home from a hard day at work and snuggle up to Shakespeare.

Here is a handout we often give to parents to provide some practical tips on ways to foster a love of reading.

Parents want what is best for their children, and they have both the challenge and opportunity to mold the dispositions of the readers in their lives. Sometimes when we say a book is too difficult, what they are really hearing us say is that their child is not a good reader. We need to educate them about reading theory and explain the reasons we have for matching text to readers. At the same time, we need to encourage parents to share their passions with their children and to remind them that dispositions are caught, not taught — it is parents who most often instill the love of reading in their children.