As a paid college notetaker, I shudder to think of the poor students who reviewed my laborious notes. Possibly the sole qualifications of that position were someone who meets deadlines and has legible handwriting. Because there was no requirement that one be able to actually take effective notes, I ended up in the course Dinosaurs 101 with my handy dandy notepad ready to earn $10 per class. The professor was a mere speck on the stage behind the podium, but when he started speaking I knew that the note subscribers and I were in trouble.

In the first ten minutes Professausarus Rex (as I nicknamed him) rattled off 50 dinosaur names that I could not identify, pronounce, or spell. My single notetaking skill was to write as fast as I could and try to get everything down, which is why the note subscribers got short novels of notes every class. I only hope they lined their pet cages with them, because I can’t imagine the notes were useful for anything else.

Not Naturally Notetakers

Effective notetaking involves a writer making meaning with his or her notes by distinguishing what is absolutely essential to know, good to know, and nice to know. In other words, good notetaking involves thinking and decision-making. Verbatim notetaking is the least effective way to take notes (for more information on notetaking, I recommend Classroom Instruction that Works: Research-Based Strategies for Increasing Student Achievement. I discovered this firsthand when I gave a preassessment to first through sixth graders.

“Take notes,” I instructed them, “in the way that is best for you.”

The younger students took notes on tigers while the intermediate students took notes on roller coasters, but the results were essentially the same: almost every student quickly wrote down as much as he or she could. Some wrote notes in a cluster while others wrote them as prose, but they still tried to get as much information as they possibly could onto the page.

At the next staff meeting I showed the notes to teachers and they were surprised. “But I have been teaching two-column notes since September,” one fourth-grade teacher exclaimed. “Not one of them used two-column notes!”

Teachers then listed all the forms that they give students to take notes, and it began to make sense. Students could successfully take notes on a graphic organizer in the context of an assigned project, but they weren’t transferring the skills. Taking notes was something they did for THAT teacher or THAT project — not for themselves.

I wanted to find a way to take notes where students learned to make their own organizers, and used the notes to make meaning. A successful approach that I’ve taught for years is combination notes.

Combination Notes

“What do you expect to get on a combination pizza?” I ask students as I start my notetaking lesson.

“Pepperoni!” “Sausage!” “Onions!”

“Anchovies!” And then every student says “ewww,” even though some have never tasted anchovies or may not even know what they are.

“Yes,” I say. “Combination means more than one topping on the pizza. So when I say combination notes you can think of more than one part that goes into the notes.”

I have students take a piece of paper — blank or lined — and fold over the right third to make a crease (that’s about four kid fingers with the thumb tucked in). Then they fold up the bottom about the length of one thumb and crease the page. To finish up they label each of the sections: Words, Pictures and Summary (see diagram).

Important to Note

Combination notes are a take-off of Cornell notes used in college and have solid roots in brain science. In combination notes, students represent an idea, fact, or event in a few words and then symbolically represent it to the right in pictures. Our brains like to be dually stimulated as we make meaning. In addition, there is the summary space provided to focus in on what is most important. This space encourages writers to revisit and revise our notes as we go.

I like to use Lila Prap’s book Why? as I teach primary students how to use combination notes. For example, as I open to the passage on Zebras, I read it aloud the first time so that kids can hear it in its entirety.

“Every zebra has a different and unique stripe pattern, just as every person has a different and unique fingerprint. Their stripes can be used to tell them apart, but many scientists believe their stripes also help confuse predators.”

“What’s this about?” I start.

“Zebras,” they say.

“What about zebras?” I say.

“About their stripes.”

I then do a think aloud of what is important to keep, and explain how I limit my words.

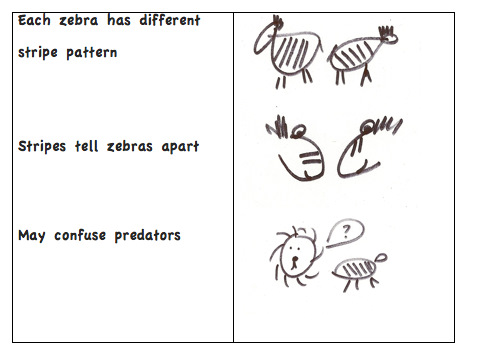

Each time I record something in words, I move over to the right column and draw a representation.

Each zebra has a different stripe pattern

Stripes tell zebras apart

May confuse predators

I point out that my representations just need to make sense to me, and demonstrate how I spend about 20 seconds on each quick sketch. Zebra portraits can come at another time.

“Why didn’t I include something about the human fingerprint?” I ask.

“Because that was just a catchy lead,” a second grader says. “It’s not about the zebra stripes.” I enjoy hearing the language from their writing workshop enter into the discussion, and realize that most of the time we don’t take notes on catchy leads. Leads have an important, but very different, purpose.

Who Teaches Notetaking?

When meeting with a team of intermediate teachers, we were selecting a reading and writing strategy to support comprehension of nonfiction texts. One teacher ruled out notes. She explained, “They really don’t need that skill until middle school. I know teachers do a lot with notetaking then.”

As a parent, I was surprised to see an ‘F’ among a column of A’s during a middle school progress conference for one of my children. The teacher saw me eyeing it and said, “Oh yes, many students failed the notetaking pre-test. They try to write everything down verbatim instead of breaking information down into chunks.”

“Who teaches students how to take effective notes?” I asked.

“That is a skill they learn in elementary school,” she said.

Both teachers are right. We need to be teaching students how to take notes in elementary school, and we need to be teaching notetaking skills in upper grades too. As text gets more difficult and notetakers have a variety of structures to choose from, they need support to customize their notes in a way that helps them remember and review information.

And it’s not just effective for students. Recently I was taking notes during a presentation on inquiry circles by Harvey “Smokey” Daniels, and right after I wrote down “I.C. (inquiry circles) are at the intersection of comprhsn, collab, and inq,” I drew a quick sketch of an intersection of the roads of comprehension, collaboration and inquiry. What an easy way to bookmark that essential idea.

Putting It All Together

The research on notetaking says that a variety of structures (cluster notes, combination notes, two-column notes, three-column notes and more) can be effective when students make meaning and actually USE their notes. Reviewing and revising notes play into how notetaking impacts achievement positively, which is where the bottom box for summary in the combination notes comes in.

With primary students in the zebra example, I discussed, modeled, and used shared writing for the zebra summary. My summary read, “Stripes help tell zebras apart, but confuse predators.” As students get older, I gradually release the summary statement to them with explicit instruction.

Just imagine if you had left an empty box at the bottom of your college notes and at the end of the day, you took the time to reread your notes and wrote a simple statement of what was important in those notes. In this scenario, you returned a few times to those summary statements and made revisions as you learned more. In a class focused on big ideas and concepts, those bottom-line summary statements could have been a very powerful study tool. I can only imagine what I might have learned in Dinosaurs 101!