Each extended family, workplace, and classroom has those innovative, creative members who bring a refreshing flair to the scene. Nonfiction’s extended text family is no different. Infographics are those interesting and unique relatives, bringing a blend of informational writing and visuals to our reading lives. As infographics have become more and more common across all kinds of publications, students are learning how to navigate these informational hybrids. Spanning a wide design world, infographics may capitalize on the following:

- Powerful images and photos

- Labels and/or captions

- Short, info-packed texts

- Interesting fonts

- An intentional use of color

- Embedded videos

- Hyperlinks for further reading

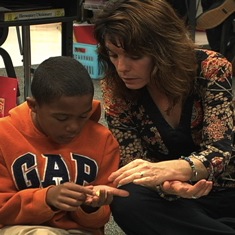

When students encounter a new text format like infographics, they need time to explore these visual messages. To encourage exploration, a museum-tour-style encounter creates a playful introduction for students. Collect as many infographics as possible; the more colorful and attractive they are, the better. Provide simple infographics for the launch, laminated copies that can be displayed across tables, in wall space, and on the Smartboard. I also create a page on our class website with embedded infographics and links to digital infographics so students can access these resources with iPads or laptops now and in the future. Here are a few guiding questions to help your introduction and museum-tour exploration time:

- Why do you think writers and graphic artists team up to create infographics? Why create infographics instead of typical pieces of text with added images?

- Do infographics have titles? Is this a useful element? Why? What do titles do on the page?

- How are infographics organized?

- What elements help you read an infographic?

- How can you find the purpose of an infographic?

- Where and when are infographics used?

- Why do you like/dislike an infographic?

During our introduction and first encounters with many different kinds of informational resources, the intention is only to become familiar with infographics. Later in the fall, my students participate in a reading/writing unit of study focused on comprehending and developing infographics when we will deepen our understanding of infographics and the connected comprehension strategies and text structures.

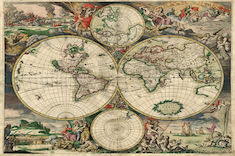

Maps

Children love having time to study the artistic form of information found in maps. Whether you give children poster maps, atlases, embedded maps on a text page, or digital maps, they are intrigued with 2-D representations of their world. Learning to extract information from the carefully constructed maps sharpens readers’ observational skills. How can children spend time exploring maps as interested and effective readers of visual information?

I begin with a short warm-up time with our map collection. Before I even begin talking about the purpose and informational elements of a map, I provide students time to browse and study maps just as one walks through an art exhibit. I spread maps around the room, using all available tabletops and wall space so students can roam the room, observing and talking about the map collection with a partner. Students need time to take in the visual information and connect to the work. The only directive I give on the first exploration of maps is a posted reminder of our See-Think-Wonder routine. I have found this thoughtful question routine to be a welcoming invitation for students’ first work with maps.

- What do you see?

- What do you think?

- What makes you wonder?

Once our map explorations are finished, I can direct students’ attention to the informational elements that will maximize our understanding of maps.

- Title: What does the title tell you about this map? What do you expect to learn?

- Information: What kind of information is shared on this map? How is the information presented?

- Map Elements: How does the compass rose, key, scale, and text help you as a reader?

- Purpose: What do you think is the purpose of this map? How could this help you as a learner?

- Color: How did the map maker or cartographer use color to support information?

- Symbols and Images: Does the map communicate information with symbols and/or images?

- Publication Date: When was this map published? Is the date important, or has information changed? Can you find a map of the same location with a different publication date so you can compare the visual information?

- Questions: If you could talk to the map maker or cartographer who created this map, what questions would you ask? Does anything about this map confuse you?

During a future exploration of maps, I will ask students to use the presented elements to carefully study one map. Students use a map observation sheet created from the list of map elements; the observation sheet supports students’ thinking about the presented visual information and helps them collect their observations. Even though students will be spending extended time with maps during science, math, and social studies, it is important for them to view maps as readers, spending time with the fascinating visual information that challenges us to be active problem solvers as we read.

Map Collections

Collecting maps is easy if you ask for maps before you actually need them. Once you put out a public call to your classroom families and your own extended family, it is surprising how many maps can be donated. Tap into local resources like the Division of Natural Resources, the Army Corps of Engineers, and related county agencies; they often have free maps for the public. Take advantage of the digital maps that are free for classroom use. Here are two useful websites for digital maps:

Nat Geo’s Map Resources for Kids: http://www.nationalgeographic.com/kids-world-atlas/maps.html

Maps for Kids: http://www.mapsofworld.com/kids/

A Simple Mission

In our current print and digital ecosystem, children have instant, unlimited access to wide-open fields of information. No matter their interests, questions, or problems, students are adrift in a swirling sea of knowledge. Our first challenge is helping them realize there are no boundaries to independent learning. One way students can find independence is through our helping them discover, access, and navigate the most useful and inspiring print and digital resources; students need to know where and how to wander and roam as learners. Nurturing the confidence to explore is one of our teaching priorities.

Our second challenge is to support our students’ sense of wonder about our world; cultivating students’ desire to explore the possibilities will now and ever be a personal mission I set down as a challenge for myself and my colleagues. True learning begins when we crash beyond the learning expectations of others, whether they be directives, standards, or a course syllabus, giving students time and space to create their own learning territories.

If we want our children to be 21st-century explorers creating new technologies, finding new information, and discovering new cures, then we need a culture of amazement. Learners will need enthusiasm, astonishment, and nonstop tenacity to step into the roles of scientists, artists, researchers, inventors, and creative difference makers.

If we model the joy of free-range learning, our children can willingly adopt this norm. If we make learning a visible celebration for students, then the classroom community becomes a nurturing place for wonder. The truth is, children are innately curious . . . They just need us to value their time, their enthusiasm, and their freedom to be amazed learners.