There is a difference, subtle though it may be, between informational and explanatory writing. Let’s take a deeper look at the moves writers use to explain beyond merely explaining how and why.

As I often do, I start with a mentor or model text, zooming in on the small and large moves writers make to explain. Here is a paragraph from Sneed B. Collard’s Most Fun Book Ever About Lizards:

The lizard menu stretches longer than an unraveled roll of toilet paper. Some lizards, such as the bearded dragon, are omnivores. They dine on a wide variety of plant and animal dishes. Other lizards, such as the common iguana, are vegetarian and eat mainly leaves, flowers, and fruit. However, most other lizard species stick to a lively diet. Anoles, for instance, provide top-notch pest-control services by devouring insects. Other lizards eat birds, rodents, worms, deer, other reptiles — almost anything that runs, crawls, flies, or breathes.

As I discuss in my book Ten Things Every Writer Needs to Know, my students and I look at model writing as a scientist would: observing, questioning, hypothesizing, experimenting, and concluding.

The Scientific Method of Learning from Models

Observing starts with the first read of a text excerpt. Initially, we read to understand. Once the excerpt has been read we move to questioning. In this case, we ask, “What is this writer doing to explain?” We begin to interact with the text sentence by sentence.

The lizard menu stretches longer than an unraveled roll of toilet paper.

Students notice Collard uses a comparison to a familiar object, toilet paper. They notice the comparison is visual, enhancing our understanding that the menu is long. Students are beginning to name, or hypothesize, what writers do to explain.

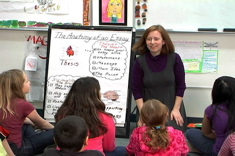

One student even notices that the first sentence tells us exactly what the paragraph is about, naming its focus. “Yes,” I say, “in explanatory writing it’s often expected that writers are clear about what exactly they are explaining.” We summarize and chart the things Collard did to explain in this sentence, adding to it as we zoom in on each of the other sentences (See chart below).

Some lizards, such as the bearded dragon, are omnivores.

“He’s giving examples,” a student says.

“Yes, examples are the lifeblood of explanatory writing. Examples help our reader understand.”

They dine on a wide variety of plant and animal dishes.

With some prompting to look at the preceding sentence, students notice the author is defining what an omnivore is. We add define to the list. “If we were explaining a hobby, besides using comparisons and examples, we might need to define certain words for our reader.”

|

Moves Writers Use to Explain |

|

• Compare to something familiar • Give visuals • State focus • Use examples • List • Classify or group This chart only covers the first four sentences. Can you see other moves? |

Other lizards, such as the common iguana, are vegetarian and eat mainly leaves, flowers, and fruit.

Of course students notice examples again, but I push them, asking, “What’s a new way Collard is explaining? What structure is he using for his examples?’

“Lists!”

We add to the chart.

Now the class's attention is starting to wane. But I want to get in at least one more thing. Beating a dead mentor text is a Cardinal sin.

“Let’s look at a cluster of sentences,” I say, “because I see something happening here.”

Some lizards, such as the bearded dragon, are omnivores. They dine on a wide variety of plant and animal dishes. Other lizards, such as the common iguana, are vegetarian and eat mainly leaves, flowers, and fruit.

They point out how the author contrasts different lizards, but I keep pushing, and finally I explain: “Some do this, others do this. This is a really important form of organizing explanatory texts — classification. We classify groups: omnivores versus carnivores. If I were writing about video games, I might organize my ideas around types of games. Gameboy or Wii versus another way that you sort video games that I don’t even know about. Grouping information into Pros/Cons, Good/Bad, is a great go-to move to explain something.”

Though there is more to learn from this paragraph, I save it for another time. In the next few days, we’ll experiment with some of these explanatory moves from our list, explaining a hobby or something we enjoy. The conclusion will reflect on how these moves helped us explain as well as discover new moves writers in the class made. We add those to our growing list of moves writers use to explain.