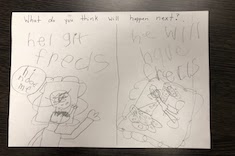

“You’re here!” Lora Bieghler said as she bounced into my office. “I’m so glad, because I want you to see this first-grade response to Freckle Juice.” Lora’s arms were full of books and student writing. She dropped everything on my table and then sorted through the student work. “Here it is!” Lora pulled one of the responses out of the stack of paper, and I leaned in to see it.

“Just take a minute to really look,” Lora said.

“Is that a mirror? Did he draw the reflection?” I asked.

“YES!” Lora exclaimed. “Look at the details . . . There’s the outside of the mirror and the back of the head. Check out the arm and the reflection. And of course, there are the freckles.”

We stare at the page in silence.

“Look at the speech bubble,” I said, pointing to the left side of the illustration. “It says, ‘Hi new me’!”

Lora looked up and grinned. “Isn’t it great? I’m so glad you’re here to see it. Too many other people would get all hung up on the conventions. Plus, they’d want to talk about how his partner ‘copied’ him.” Lora swung her hand over the other side of the response, and I noted the replica of the mirror.

We continued to marvel at the wisdom of the way the first grader shared deep meaning in his illustration. Lora left my office, and the question that has been nipping at me poked again.

Do We Marvel Enough?

What makes some educators enamored with the brilliance of this reading response, whereas others question the lack of ending punctuation and capital letters? How often do students show us deep understandings, but we miss them because they don’t come in the package we expect?

This happens with not only primary writers but all students. It happens when they make innovative moves to identify theme or find evidence to support a thesis. Sometimes the jumps are off a bit, and we miss the brilliance in the attempt of what students are almost doing.

How to Marvel

- Ignore the errors. For many of us, conventional errors jump off the page and slap us in the face. We must train ourselves to ignore the errors. It’s easy to see the things that are wrong, but they aren’t nearly as important as the work students do on purpose. To marvel at students, we must learn to overlook incorrect conventions.

- Assume intent. Let’s adopt a mindset that happenstance isn’t an explanation. It wasn’t an accident that this student created a mirror image to represent the change in a character. It wasn’t a coincidence that he added a speech bubble. Those were intentional meaning-making moves. Too often, we miss the chance to marvel by assuming students do things by accident. It’s just as reasonable to assume intent, and the benefits are more positive.

- Notice change. When we look at student work and ask, “What are students doing now that they weren’t before?” we place a lens through which to see growth. Typically, growth isn’t linear. For example, we might notice apostrophes springing up in student writing. It is unlikely that the apostrophes are going to be used perfectly. Rather than discounting the change, we can learn to acknowledge the growth. In this example, we could marvel at students being more aware of apostrophes than they were before.

Why Marvel?

When we marvel at students, we validate them. In essence we say, “You are amazing. You matter. You know so much, and I’m glad I get to be your teacher.” Validation helps develop a strong relationship while lifting students up. Marveling at students also helps teachers see the growth that is happening in learning. It helps teachers feel like the work we do is making a difference. In the midst of our busy days, let’s not forget to marvel!