A good discussion increases the dimensions of everyone who takes part.

Randolph Bourne

“I can’t believe they just left her behind on purpose,” laments Danielle, gripping her book and slamming it against her knee. “I was soooo mad.”

“I know, right?” Julia says. “Can you believe a teacher would do that? What did you think, Sadie?”

I am listening in on a conversation about Sharon Draper’s Out of My Mind. The group has just read a pivotal section of the emotional novel, and the discussion is energetic and animated as they share their strong feeling with one another. This discussion took place in the spring after they had spent the year developing their discussion skills.

A couple of years ago, I had the good fortune of sitting in on a conference session led by the amazing team of Kylene Beers and Bob Probst. At one point during the session, they showed a video of eighth graders discussing a novel. The group of four students were engaged and self-directed, and clearly had worked on how to have a literary discussion. They asked questions, built off of each other’s thinking, and shared different points of view, respectfully, all without a teacher directing the conversation. The discussion seemed to be deepening their understanding and appreciation of the book.

The session and those students inspired me to try using student-led discussions with small-group novels in my fourth-grade classroom. Later in the same school year, I gave it a try and it was a colossal disaster. Without practice with how to have discussions, asking good questions, or having many expectations for participation, the meetings were a free-for-all where the most chatty student dominated the conversation and some students just sat back and watched. I had been so excited to try something new that I had neglected to think about all the steps it takes to get there.

The following summer I spent a lot of time thinking about how to do things differently and asked myself the following questions:

-

Why is student-led discussion important?

-

Are fourth graders developmentally ready for this kind of discussion?

-

What skills are necessary to hold a successful discussion?

-

What scaffolds and resources can I put in place to have the best chance of success?

After doing a bit more research and thinking, I realized that my goal was for my students to have a more natural and authentic way to respond to their reading than teacher-led questions or assigned roles to share. I wanted the students to have discussions that deepened and extended their understanding and enjoyment of the book that would resemble how adult readers respond in discussions or book clubs. Although the students were not used to this kind of exchange, I believed they were capable of learning the necessary skills and strategies to be successful with student-led discussions.

We spent the first couple of months building a solid foundation that would serve us well in any kind of discussion. We started by talking about why we have discussions.

After clarifying some of the reasons why we discuss, we talked about what a good discussion looks like:

- facing each other

- active listening the whole time

- taking turns

- involving everyone

- asking and answering questions

We delved a bit further into each of the components of having successful discussions and created anchor charts.

Because the students needed to be able to ask each other thoughtful questions that would lead to discussion, we spent a lot of time on this skill. We used the term spark discussion when analyzing questions. This kind of questioning required the students to be able to predict how others might respond. They quickly discovered that questions with a yes-or-no answer and questions with a correct answer did not elicit much discussion.

The students also noticed that to keep the discussion going, participants needed to be willing to explain the reasons why they were answering a question or responding to a comment in a particular way.

We spent several weeks practicing these new skills in partnerships. We modeled and analyzed discussions in front of the class, using our resources to evaluate the questions and participation. By early November we were just about ready to start our student-led discussions. I thought it was important to be clear about what would need to happen during the discussions to avoid the chaotic meetings of the year before.

I decided on the following:

- The group would decide together how many pages to read before the meeting.

- The group would decide on a date for the meeting.

- For each meeting, one person would start the discussion by quickly retelling the major events in the section they read.

- Each person would come with one good question or comment to present to the group that would spark conversation.

- After the meeting, the group would decide the next bit of reading and decide who would retell.

I knew that the students would still require coaching during their meetings, especially the first round in the fall, but I felt confident that they were ready to begin.

What Went Well

- The students were excited about their books and about meeting with peers. They worked hard to negotiate the number of pages and encouraged each other to finish in a timely manner.

- Many had good questions and comments to present to the group.

What Could Have Gone Better

- Some students would arrive to the group without a question or comment written down.

- Several questions were surface-level or had a correct answer that could be found in the text.

- Students still relied heavily on my presence to keep the conversation going, build upon ideas, and make sure everyone was given an opportunity to participate.

- The “reteller” was not always prepared to retell.

- Students with strong verbal skills were dominating the conversation.

Since the students were so used to answering questions about a text from a teacher (many with a “correct” answer), they really struggled with the idea that I did not want to lead the group. They also were not thinking deeply while reading or using the charts we created.

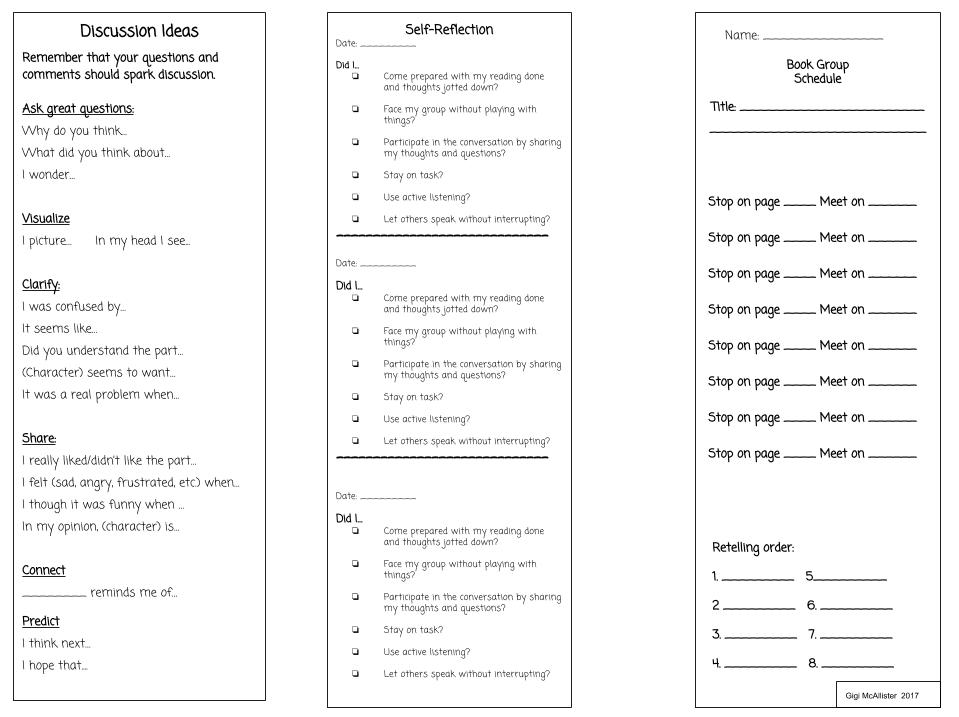

We continued our practice with good questions and comments that others would want to discuss, and the students improved a lot in that area. We drafted some discussion ideas and question stems to use as a reference. We also created a checklist for students to self-assess their participation.

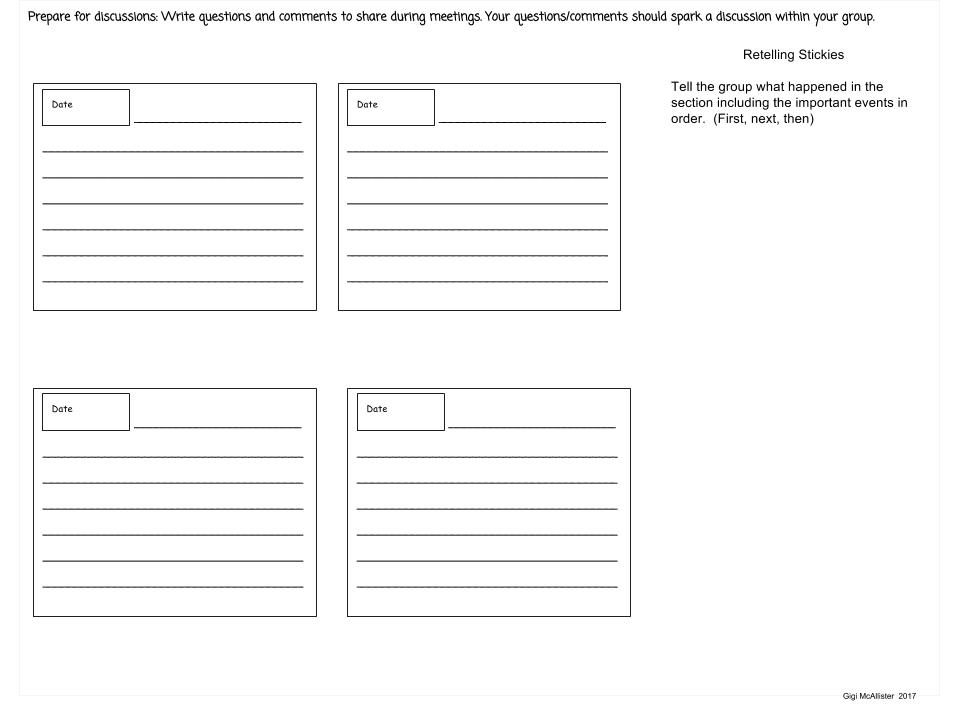

To help ensure that everyone came with questions, I decided to create a document that would serve as a place for the students to write their questions, keep track of meeting dates, self-assess their participation, and hold resources for writing good questions and comments. It folded into a three-section bookmark. The group met only after everyone had a question or comment written down.

Side 1:

Side 2:

With all these scaffolds in place, the next round went much better, and by the last one in the spring, most students hardly needed me at all. Although the conversation might not always have gone smoothly, I think the students improved their ability to hold a developmentally appropriate literature discussion.

It takes time—not days or weeks, but months—of circling back to help students refine and reflect upon their discussion skills. Working on discussion skills every day shows students that discussion is valued as much as reading and writing.