an·no·tate

VERB

annotates (third person present) · annotated (past tense) · annotated (past participle) · annotating (present participle)

-

add notes to (a text or diagram) giving explanation or comment.

(Definition from the Oxford Dictionary)

My students annotate like crazy. Whether you pop into the classroom during read aloud or independent reading time, many students have tools with them as they read. These are often sticky notes, notebooks, or handheld devices that they are using to annotate their thinking.

I am not so worried about the actual annotations, but I’ve found that supporting annotations does a few things for readers. First of all it helps them get into the habit of stopping to think. Too often, students read books quickly without considering all there is to them. As books become more complex, they learn to read at a very surface level without support. Second, deciding how to annotate gives them a way to think about what the book offers and what things they might think about as the book progresses. It builds an intellectual curiosity that leads to deeper understanding.

Small Spiral Notebook

Our first experiences with annotating are during read aloud. During our first read aloud I give each child a very small spiral notebook and ask them to jot while we read. I don’t give much more direction. Several times each day I’ll stop reading and give them time to stop and jot. Then we chat. This small notebook serves two purposes. It helps set the stage for this routine as part of our read aloud, and it helps me see the ways in which they think while reading. Often in the intermediate grades, students have experience writing after they read but writing during reading is a new experience.

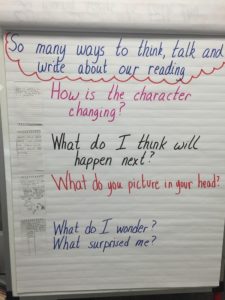

During this first jot, I am watching closely to see all that they do. This first experience with annotations tells me whether students are comfortable writing as they read as well as the kinds of things they notice. I look for patterns across the class and also unique ways of annotating that I might share. I notice which students focus on summarizing what happens and which add their own thinking to their annotations. After a week or two, we highlight a few possibilities by sharing under the document camera or collecting possible ways to annotate (using student examples) on a chart. This chart gives students ideas for new ways to annotate. It also invites them to try something not on the chart, because part of building the chart together is understanding that it will grow as we find more ways to annotate. It is also a time to sit back and discuss how each of these strategies helps us understand the text, the ultimate goal of annotating.

Moving Beyond the Small Notebook

After that first read aloud, we build our understanding of what is possible as we move into our second read aloud. For this read aloud, I let students know that they can continue to use the small notebook. But they can also choose to use a regular-size notebook or one of the digital apps that I’ve shared or that they know of on their device. I often share this video (https://youtu.be/17E0QkeuZpQ) as a way to show students some possibilities with some digital tools that are available on our classroom devices.

Again, my role is to watch and listen. This time, I am looking for things that add to what we have on our chart. I am also looking for new ways students are organizing their annotations and keeping an eye out for how they are using new digital tools. Did anyone create columns? Did anyone use another type of graphic organizer? Who is using both words and sketches? Quick shares of these things give students more options for their own annotations. I continue to ask, “How is this helping you understand what you read?”

To Model or Not to Model

I am often asked whether I model all of this before we begin annotations. My answer is a firm no. If I modeled, I know my students would merely mimic what I model. With something so new to so many of them, they would see my modeling as a template of what I expected them to do. Instead I want them to find annotation strategies that work for them, that help build understanding. And I also want to build the idea that different annotation strategies and tools work for different purposes. Instead of modeling, I look for strategies and tools students are using when given the task, and I give them opportunities to share. I have found that students find ways to annotate that they’d never discover if I had modeled my way first.

Modeling certainly has a place in this learning cycle, and I often model later in the year, once students trust that I do not have a hidden agenda for their annotations. Instead I model as another option once they are comfortable. I model as a way to share new possibilities and to start the conversation about annotating in a way that is specific to the book.

Opening Possibilities with Shared Annotations

For example, during our read aloud of Wonder by R. J. Palacio, I took advantage of the book’s setup to create a chart we would use for our shared annotations. The book is designed to invite thinking about the characters’ various perspectives. I created a chart with each part/character and we summarized what we learned about the character and his/her perspective while reading those sections. Although students had their own annotations in a notebook or on a device, together we were thinking on the chart shown here.

For example, during our read aloud of Wonder by R. J. Palacio, I took advantage of the book’s setup to create a chart we would use for our shared annotations. The book is designed to invite thinking about the characters’ various perspectives. I created a chart with each part/character and we summarized what we learned about the character and his/her perspective while reading those sections. Although students had their own annotations in a notebook or on a device, together we were thinking on the chart shown here.

Thinking Across a Text

Another thing that I introduce during this second or third read aloud is the idea of thinking about some big idea across an entire text. This often comes from a question that we know will not be answered easily. We call these big questions. When we read Wonder, we thought about these questions after we had read for a few days. We each committed to a question we wanted to consider as we read through the text. We posted those on the cabinet near the read-aloud areas as a visual reminder that we were holding on to some big ideas during this read.

I often build on the idea of tracking a question across a text by finding lines in the text that help answer it. It is usually during this read aloud that I also want students to see what it is like to annotate in the text using a digital tool, so I often read the book aloud as I project it on the screen.

Using Previews to Ask Better Questions

As students become comfortable thinking about a big idea across a text, we often learn to use our previewing skill in more sophisticated ways. We may spend a full read-aloud time or two to preview our new read aloud. Sometimes this means that together we read the inside flap, read the back, look at the table of contents, read the first few pages, and so on. By the third or fourth read aloud, students are ready to preview on their own as a way to get their brains ready for the book and the kinds of thinking it might invite.

I often give students a page of the things we preview so that they can jot right on the preview features. Our follow-up conversation often uncovers a great deal about the kinds of things we might find ourselves thinking about as we read. For example, as students previewed Naomi Shihab Nye’s Turtle of Oman, many realized that the main character, Aref, would change throughout the book and they wanted to pay attention to those changes. They also wondered whether the ‘turtle” in the title symbolized something because it was singular—if it had been referring to the actual turtles of Oman, they assumed there would be more than one. These were two ideas that many students followed in conversations and jotting acrosst the book, based on the previews.

Making Our Collective Thinking Visible

As students become more sophisticated in understanding what is possible in a book, we move to a larger visual of our thinking. As students continue to annotate on their own, I use shared classroom space to invite more collective thinking. During one of our winter read alouds, Refugee by Alan Gratz, we built a board that grew across the course of the read aloud. Knowing that connecting three separate stories with three important characters was new for many students, I set up a blank board in the classroom with sections for each of the three characters. Several times during the course of the read aloud, students were invited to capture their thinking about ideas and conversations around the book. They were also invited to look at the board often to grow their own individual thinking and to try to build on others’ thinking. A board that made our growing thinking visible became an important tool to understanding with depth.

The power of annotations comes in the deep understanding children are able to acquire when they stop and think. As they learn new ways to annotate, they learn new ways to think about text. Building these skills across the year as part of our read-aloud routine invites students to think at deeper levels about all the texts they read.