I gather students in our meeting area and begin our minilesson on character development. I remind students that today we are looking at how authors reveal characters to us and how we learn about them. I begin reading Crow Call by Lois Lowry.

I read the first few pages and ask, “What are you thinking?”

Ayden asks, “Why would she have to practice saying ‘Daddy’ to herself? She seems to be scared about saying it.” He pauses, then says, “Because she is not saying it out loud. She is thinking it.”

“Ahh… so authors reveal characters through their thoughts. Let’s add that to the anchor chart.”

We continue the read aloud, searching for other ways characters are revealed to readers.

This scenario was a common practice in my fourth-grade classroom. I would teach a minilesson using read alouds or mentor texts, and we would co-create an anchor chart.

As I made the move to middle school, I questioned this practice that had become so commonplace in my elementary classroom. Did middle school teachers use anchor charts? Would middle school students think anchor charts were too babyish? Were they still an effective learning tool?

It didn’t take long for me to find the answers to those questions. Although my purpose and intent are the same, the procedure by which I make anchor charts has changed. Recently, I watched one of my middle school students look up at a chart while he was working independently, and I was reminded once again of the importance of anchor charts in any classroom.

What Is an Anchor Chart?

An anchor chart is a tool used to support instruction and learning. As a minilesson is taught, teachers and students create the chart, typically on chart paper with markers. I have also added sticky notes and sentence strips to anchor charts to add student work or examples.

There are several different kinds of charts, but I find myself using three in my middle school classroom: process, strategy, and list charts.

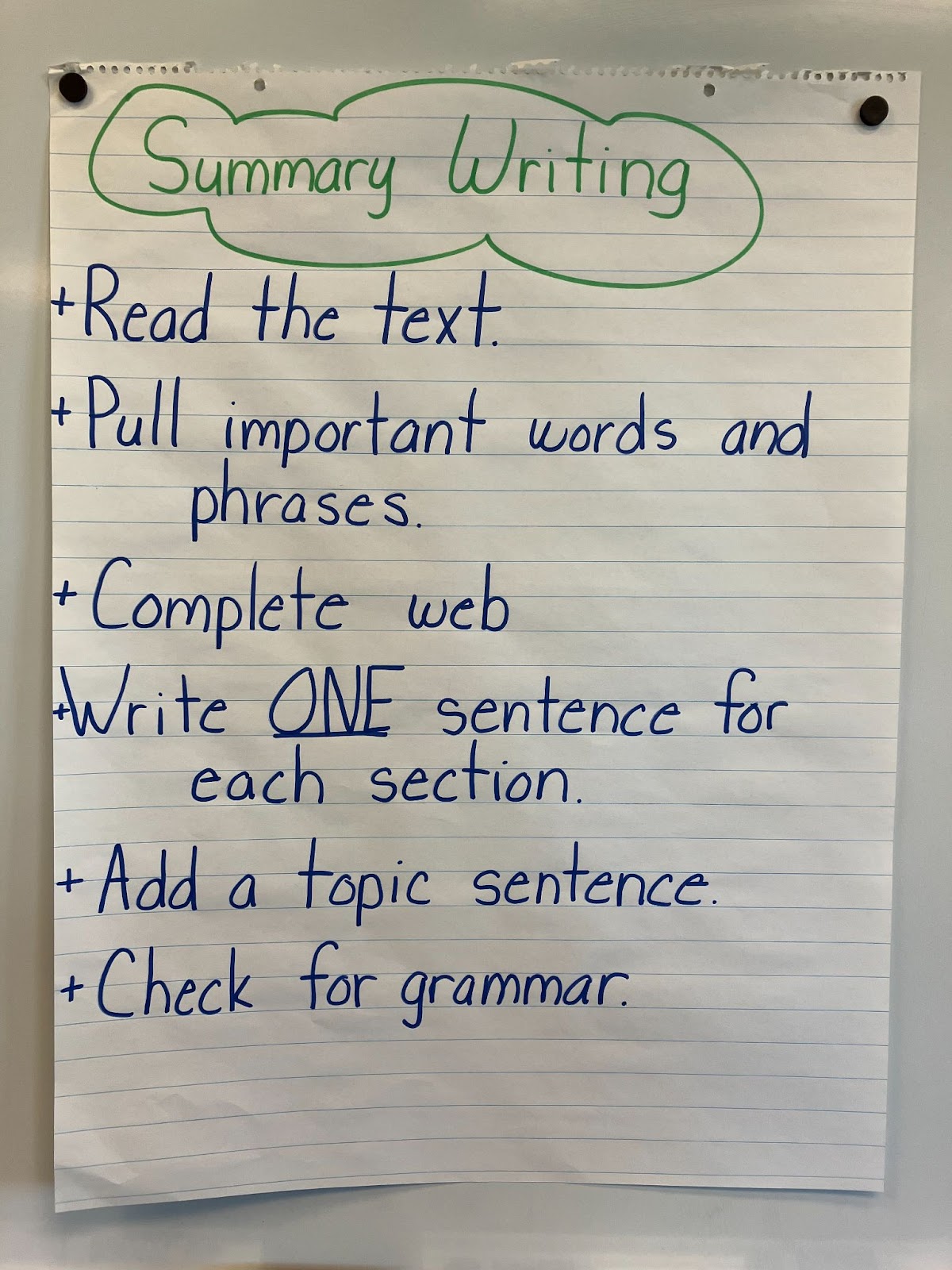

Procedural or process charts break down skills into smaller chunks or steps such as writing a summary or a central idea statement.

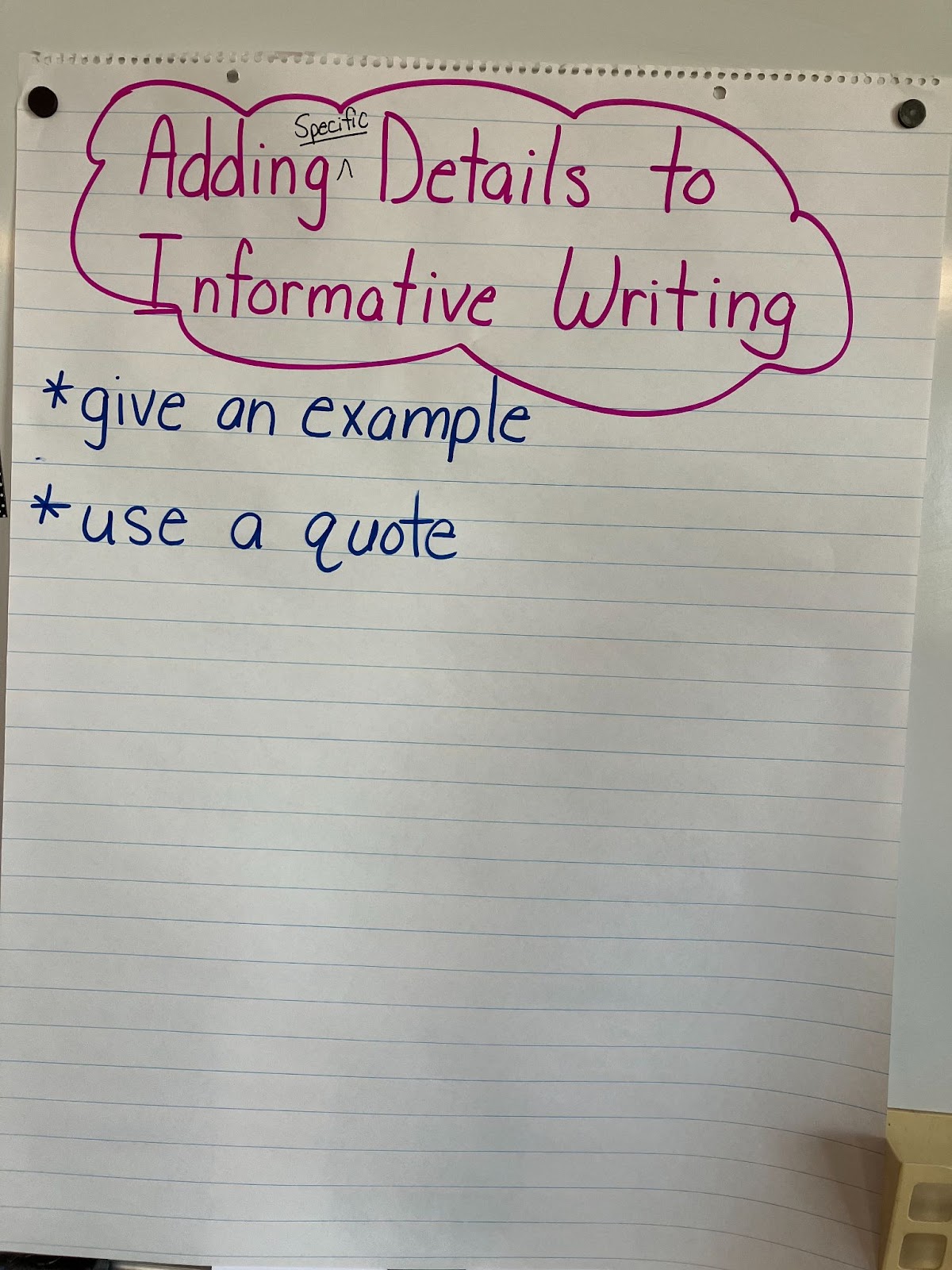

Strategy charts list strategies that help students with a more complex skill. An example of a strategy chart is a list of ways to identify how authors reveal characters or add details to informational writing.

Strategy charts list strategies that help students with a more complex skill. An example of a strategy chart is a list of ways to identify how authors reveal characters or add details to informational writing.

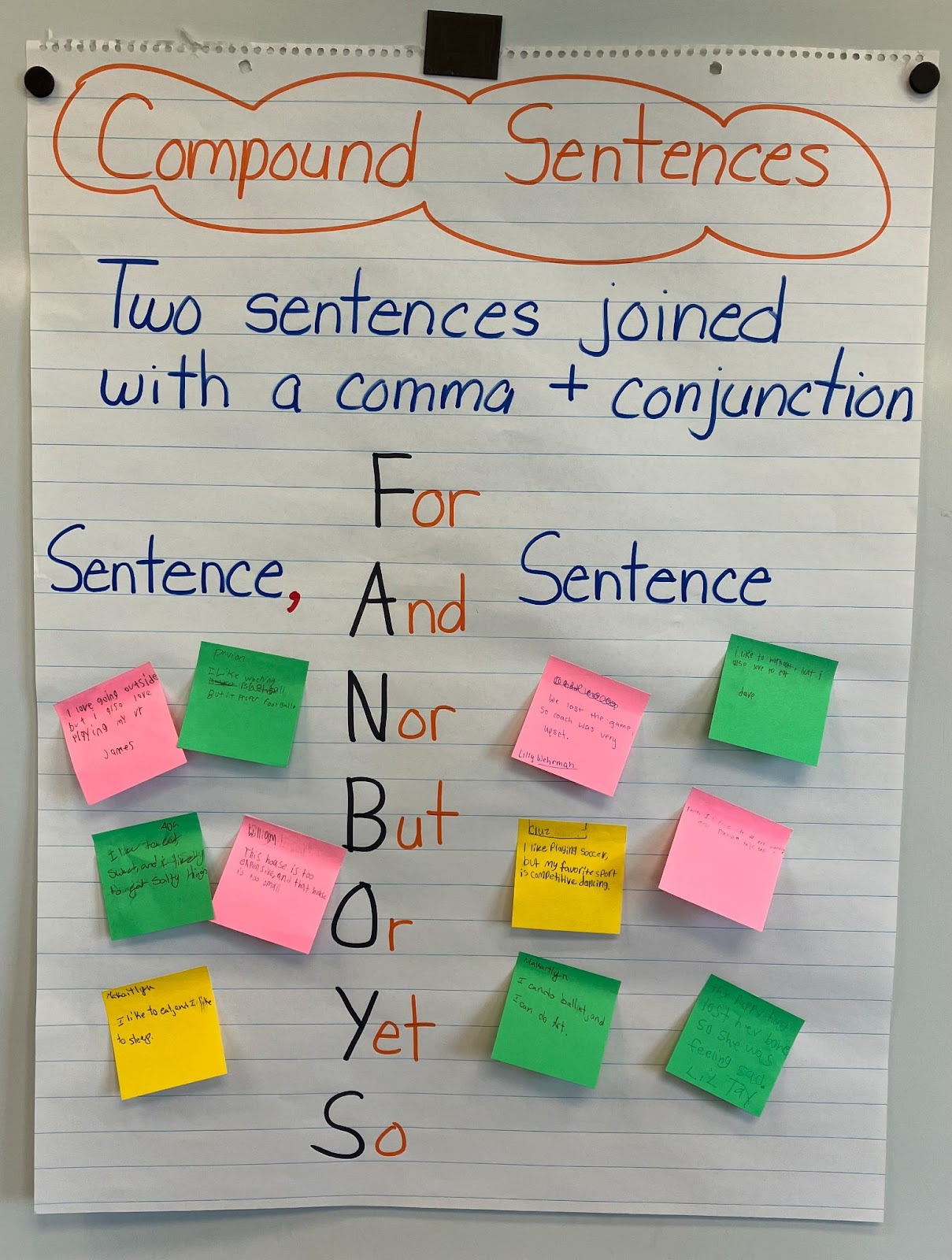

The final chart is what I call a list chart. For example, after a lesson on compound or complex sentences, I might create a chart listing the subordinating and coordinating conjunctions. In this chart, I reviewed compound sentences, because this is taught in prior grades. I had students write examples of compound sentences on sticky notes, and I added them to the chart during each period.

The final chart is what I call a list chart. For example, after a lesson on compound or complex sentences, I might create a chart listing the subordinating and coordinating conjunctions. In this chart, I reviewed compound sentences, because this is taught in prior grades. I had students write examples of compound sentences on sticky notes, and I added them to the chart during each period.

Why Use an Anchor Chart?

The basic purpose of anchor charts is to support readers and writers. I want students to reference the charts hanging in the room and to use them as they move toward independence. When we use learning tools such as anchor charts in our classrooms, we need to know why we use them and what makes them effective. Moving from the elementary level to the middle school, I learned students still needed them. An anchor chart

- supports the learning process.

- makes student thinking visible.

- increases student engagement.

- empowers students to self-monitor progress.

- encourages independence.

- creates ownership of the learning.

- connects prior learning to current learning.

How to Create an Anchor Chart

As an elementary teacher, I would make charts with my students during the lesson. I would include the students’ names on the chart next to their responses, which encouraged engagement and gave students ownership in the learning process. This worked well with a class of 20–25 students. But how would I manage this with six class periods and more than 100 students?

I tried several ways to create charts with my middle schoolers, and honestly, all of them worked, but some were more difficult for me to manage than others. At first, I created a paper chart with every class and included names just like I had in elementary school. At the end of the day, I would make one final chart with the common ideas or student responses and include all names.

I followed this idea up by taking a picture of the charts, copying them, and making a mini-chart for students to put in their notebooks. This way each class had its own chart along with the final chart displayed in the classroom. Both ideas worked, but it took too much time to manage the logistics.

Now I create the chart with every class on the whiteboard. At the end of class, I take a picture of it, which allows me to combine the thinking from every class and to see the commonalities in their responses. At the end of the day, I create a paper chart to hang in the classroom.

I do believe anchor charts are important and effective even in middle school classrooms. When I begin to doubt this, all I need to do is watch a student look up at the empty space where a chart used to hang, give a little nod of remembrance, and get right back to work. That is independence. And that is the success of using anchor charts.