It is not enough to be industrious; so are the ants. What are you industrious about?

– Henry David Thoreau

After 22 years as a high school physics teacher, my husband, Steve, jumped to “corporate,” joining Stratosyn as a learning specialist in a newly established learning academy.

It’s been fascinating to learn about corporate culture, and because I’m a lifelong teacher, my default is to consider how something Steve tells me about his work might (or can’t) translate to teaching and learning. An example is the way Stratosyn has employees track their time over the course of a day using a set of numeric codes. Although I’m not privy to the specifics, I know that there’s a code to indicate time spent in a meeting, a code to indicate time spent collaborating, a code to indicate time spent creating content.

At the midpoint of a school year, I’m primed for ideas that push me to reconsider what needs a refresh in the classroom, and this whole coding scheme got me thinking about my student writers. If I asked them to document what they did during writing time, what details would show up? Anyone who has finished a significant writing project knows there’s a strong correlation between “butt in chair” time and writing accomplished, but a writer’s success involves influences beyond sitting down in front of a notebook or a keyboard and generating text.

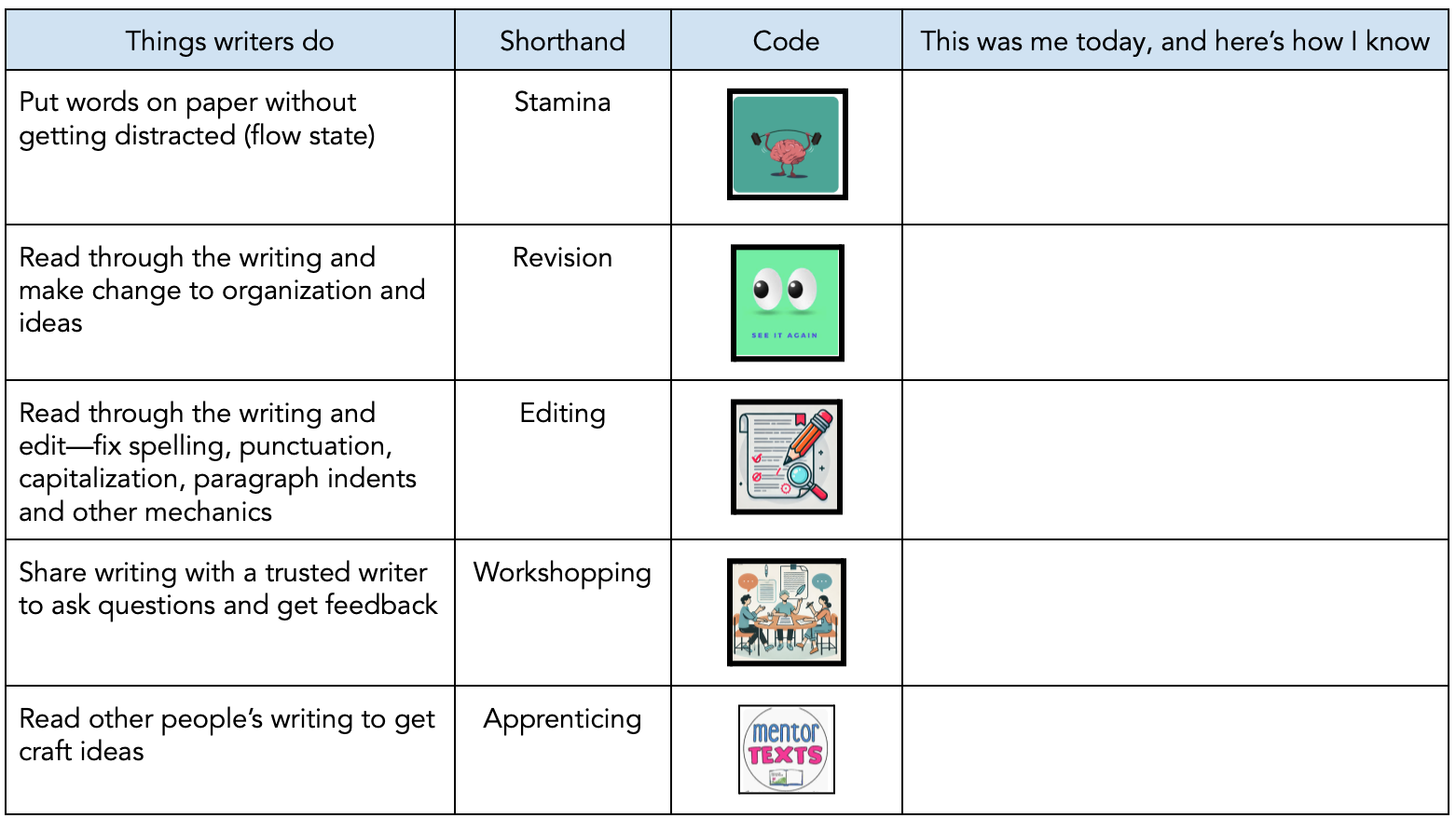

With that idea in mind, I put the question to my students: What kinds of things do writers do?

This project is hot off the presses, and as of this writing, the list below is where we are.

Writers:

- Put words on paper without getting distracted. (Flow state has been a favorite phrase since we watched this TED Talk.)

- Read through the writing and make changes to organization and ideas.

- Read through the writing and edit—fix spelling, punctuation, capitalization, paragraph indents, and other mechanics.

- Share writing with a trusted writer to ask questions and get feedback.

- Read other people’s writing to get craft ideas.

- Get lost in thought.

From here, I took over, playing around with kid-friendly icons to represent the actions on our list and then creating a chart summarizing our ideas into an organizer for reflecting on writerly work.

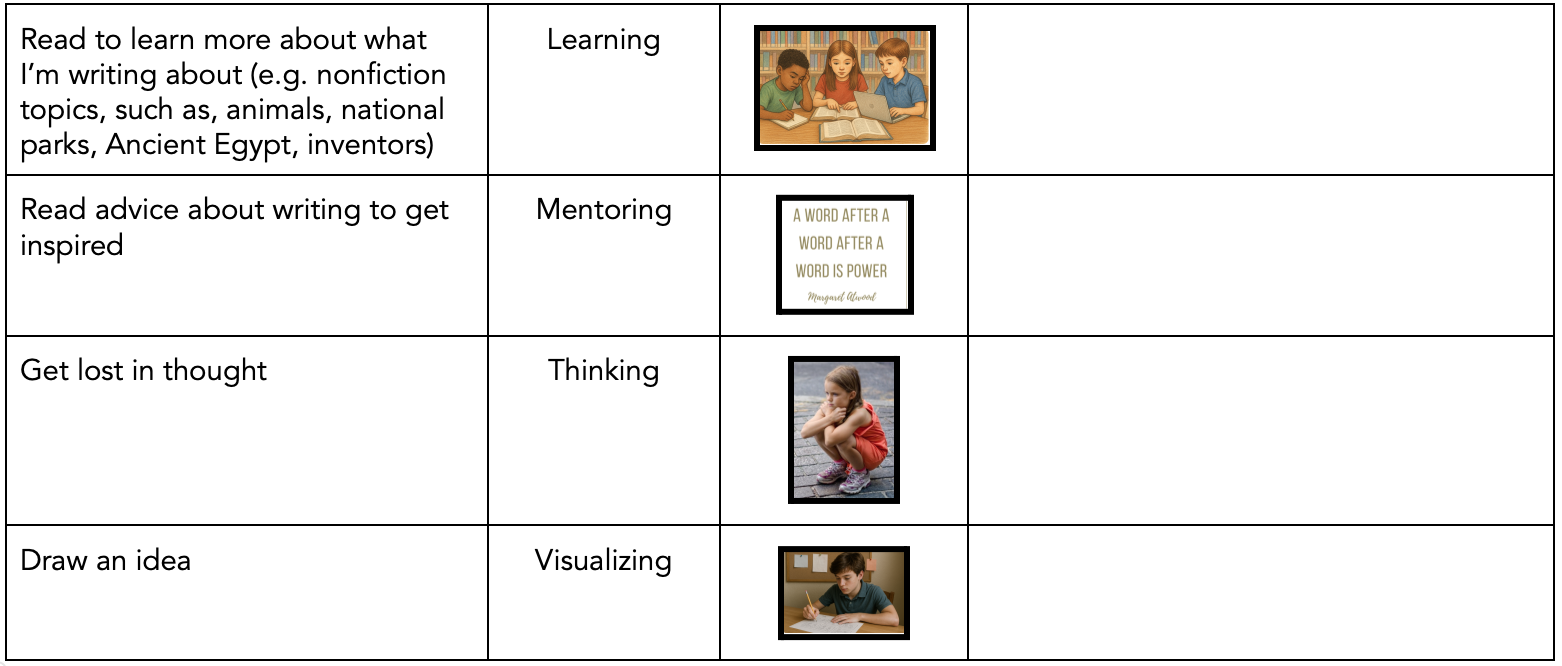

After two test-drives of our All the Writing Things tool, we talked about what was working and what needed to change. Stella noted that she had spent time reading about famous monuments, the topic of her social studies research paper. There was strong consensus among my class that doing research is a “big thing” that writers do as part of their process, so we added that move to the chart and used learning as the shorthand. Then Gio, who writes fantasy whenever he has a chance, told us that sometimes he sees the next part of a story in his mind, and instead of writing it down, he sketches it first. In response, we added “Draw an Idea” to our list of things writers do, with the shorthand visualizing. (There was also a request to convene a working group of kids who would use their artistic skills to design custom coding icons to replace my early attempts.)

According to husband Steve, Stratosyn’s practice of having folks code their time is not about individual productivity checks; instead, the codes go into a big database showing a spreadsheet of how employees spend their days, weeks, months, a year. Data can be disaggregated by division and displayed in different ways, for instance, to make a heat map; bright red shows a lot of activity within one code, soft yellow means not much “heat” generated within that code. Teams use the information to reflect, reconsider, and make new goals.

Taking the corporate concept of coding time and creating an All the Writing Things chart has been a helpful midyear tool for a couple of reasons. First, by creating it, my students and I had conversations that reinforced the dynamic, nonlinear work of writing. Getting words on paper is the goal, but the path to get there is rarely direct. When we’re reminded that reading about a topic, talking with a classmate, or sketching a scene before writing about it all count as progress toward the goal of a final piece of writing, we are building layered writer identities. Second, putting students in charge of analyzing their practice allows them to ask questions like, “What were the best and least effective ways I used my workshop time? How do I know? What support do I need to do more of what’s effective and less of what’s not?”

What’s next? We haven’t made a heat map yet, but we will. I am curious to see how, over time, my writers are doing all the writing things, and to talk with them about how different kinds of writing demand different uses of our time. No less a thinker than Henry David Thoreau asked us to consider, “What are we industrious about?,” and answering that question from our position as writers will be a valuable exercise.