Jeff Wilhelm was a new faculty member at the University of Maine when I enrolled in his graduate course called Teacher Research many years ago. The signature assignment in this class full of in-service teachers was to do a teacher research project in our own classrooms. Jeff scaffolded the process well with interesting exercises designed to teach us about data collection on a small scale—research with a little r. We learned how to collect qualitative data with tools such as sociograms, informal observation sheets, interest surveys, and reflective journaling.

The weeks ticked by, and the deadline for choosing our research focus loomed. I was in my fifth year of teaching and trying to find a tension in my instruction worth investigating. Over the summer, I’d read Literature Circles by Harvey Daniels, and although I was intrigued by the idea of student-led reading discussion groups, I was unconvinced that this approach was better than my teacher-led discussion groups.

In my classroom, I was committed to making reading as "real life" as possible and to moving my fifth graders toward independence. Teacher-directed reading groups did not align with either of those goals. I’d found my tension, not in something that wasn’t working in my classroom, but in a conflict between what I believed about effective teaching and learning, and what was really just a self-indulgent practice that allowed me to talk about books every day.

The week before our question was due, using the question starter, “What happens when . . . ?" Jeff tried to inspire us with one of his favorite sayings about teaching: “You have to be willing to put your butt over the yawning gulf”—a saying with some connection to the extreme mountaineering he’d done in the Swiss Alps. So I wiggled backward, closer to the edge, still skeptical but feeling the pressure to take a risk. What happens when I use literature circles in my reading program?

We’re All a Little New

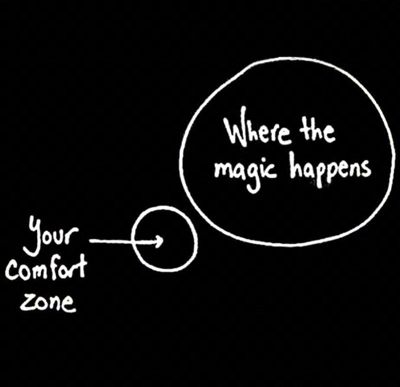

Twenty years later, my daughter is about to start 10th grade, and last week, parents received an email from a school administrator. In her letter, Ms. Rubin explained that sophomore year is all about getting outside your comfort zone. She asked us to visualize a graphic she’d found on the Internet to underscore her point. Imagine a box with two hand-drawn circles inside. One circle is labeled "your comfort zone." The other circle is labeled "where the magic happens." Tenth grade, according to Ms. Rubin, “is about intentionally pushing away from what is familiar and comfortable toward the magic of the new."

Twenty years later, my daughter is about to start 10th grade, and last week, parents received an email from a school administrator. In her letter, Ms. Rubin explained that sophomore year is all about getting outside your comfort zone. She asked us to visualize a graphic she’d found on the Internet to underscore her point. Imagine a box with two hand-drawn circles inside. One circle is labeled "your comfort zone." The other circle is labeled "where the magic happens." Tenth grade, according to Ms. Rubin, “is about intentionally pushing away from what is familiar and comfortable toward the magic of the new."

As I thought about comfort zones and magical places, I realized that the beginning of a school year makes everyone a little new—students, teachers, administrators, parents. Everyone feels a smidge of discomfort as we transition from summer to fall, learning new faces, new expectations, new needs, new mandates. Our comfort zones shrink while the unknown throbs on the margin of our consciousness. Our collective butts are teetering over the yawning gulf.

But it’s our new teachers who are really feeling it.

Those of us who work with the new folks can acknowledge that juxtaposition as intimidating, and then we can help flip the script and see that big circle as full of magical possibilities.

Here are some strategies for seeing the magic:

- Start the year asking teachers to share stories about times they stepped out of their comfort zones. We don't always see magic when we take a risk, but we always learn something that encourages us to keep trying.

- Read about risk-taking in teaching. A favorite book of mine, from back in those graduate school days, is Oops: What We Learn When Our Teaching Fails, by Power and Hubbard. It’s full of short stories describing times when teachers tried something and it didn’t work, at least in the way they expected.

I also like to use a chapter from Holding On to Good Ideas in a Time of Bad Ones, by Tom Newkirk, called "Finding a Language for Difficulty: Silences in Our Teaching Stories." This chapter teaches us to beware of the "superteacher" myth in our professional reading.

- Give teachers time to work on their list of professional bottom lines. New teachers will struggle with this; they’re still trying to figure out bus duty. Slowly but surely, though, they’ll be able to answer this question: "What matters to you in teaching and learning?" It’s a career-long pursuit but a reflective practice that’s worth starting early.

- Host "What happened when . . . ?" sessions as part of each PLC meeting or other professional development gathering. In Choice Words, Peter Johnston writes about classrooms where students are expected to talk about how they struggled with their writing and what they did to solve their problems. The message is that writing is hard work and so the hard parts become part of the conversation; if you’re not struggling as a writer, you’re not really writing. Teaching works this way too; getting uncomfortable is necessary to do the work. Honor the role of discomfort as a requirement for professional growth.

Full Circle

Turns out, what happened when I used literature circles in my reading program was humbling. My fifth graders talked about books like real readers. Right away. Without my higher-order thinking questions. They moved toward independence. Easily. In the beginning, the literature circle roles were a helpful support, but after several weeks, my readers decided the roles were limiting, and they abandoned them in favor of ideas to discuss written on sticky notes stuck to their book pages. It was "little r" evidence that magic happens in the yawning gulf.

Children are always more capable and more engaged when I seek that light touch in my teaching. New teachers are the same—capable and engaged when we encourage and reassure, eyeing the distance between what’s comfortable and what’s possible, and then taking the leap.