Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.

― attributed to Maya Angelou

I noticed something interesting about Sophia’s eyes.

I had been following along in my copy of the book we were reading when Sophia took a long pause. I knew she was stuck on a word, so I waited a few seconds before glancing up at her. That’s when I noticed her eyes. She was looking sideways, sort of. Not at the book. Not at the wall. But sort of down at the table next to the book. I sat, watching her eyes. Why was she looking at the table?

“Sophia?” I quietly nudged.

“I’m stuck,” she whispered back.

“Well, look at the book,” I suggested in a tone that could definitely have been softer.

I found myself giving Christopher similar advice later that afternoon when I noticed his eyes. He, too, was stuck on a word, but rather than staring sideways at the table, Christopher was searching for an answer on the ceiling. He sat staring at the ceiling, and I sat staring at him.

“Christopher?” I whispered.

“I’m stuck,” he whispered back.

“Well, look at the book!”

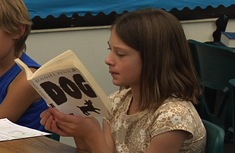

I became an avid watcher of eyes that day. Whenever I heard that telltale pause in a student’s reading, I would wait a few seconds and then look up. Sure enough, their eyes would be anywhere except on the words. Some, like Sophia and Christopher, were staring blankly at the table or ceiling. Other students’ eyes were fixed on the picture, studying it intently. Some were gazing patiently at me, waiting, I guess, for me to tell them the word. Almost none of them were looking at the one place that would help them the most—the word!

I mused over this noticing for a while. Perhaps it was the result of a learned helplessness. Sometimes when we hear those awkward pauses and see our students struggling over a word, our love for them just takes over and we blurt out the word to save them from their discomfort. So maybe these students had learned to just wait a few seconds for their teacher to tell them the answer. Or perhaps it was an indication of their lack of word-solving strategies. Sophia and Christopher didn’t really know what to do so they sat in limbo, waiting for me to give them a tool. Or perhaps these students had been taught to look at the picture to try to guess the word, so they homed in with laser-like precision at the illustration, looking for clues.

Whatever the reason, I knew their eye movements were ineffective. I knew the number-one resource available to them was the word itself. Could the picture help? Maybe. Could I? Likely. Could the ceiling? Definitely not.

The first thing I did was create a small poster. The poster simply read “Look at the word.” I drew a silly pair of googly eyes to draw attention to the poster and hung it behind our small-group table. And then I watched my students’ eyes. The next time I heard that pause in the middle of a sentence, I glanced up to see Shazil smiling at me. I smiled back and then pointed to the poster.

“Look at the word, Shazil,” I prompted.

This would be the first of many, many times that I had to prompt Shazil to look at the word. We eventually learned that what Shazil really needed was some phonics reinforcement and a tool kit of decoding strategies. That was all manageable in our intervention once Shazil got in the habit of looking at the word. I would say the single-best move I made as a reading interventionist last year was hanging up that little “Look at the word” poster.

Another shift I made was in the way I prompted students when they got stuck. Our district was making the slow switch to more decodable texts, choosing decodable books over leveled readers whenever suitable. I sat side by side with my students and listened to them read, waiting for that telltale pause. They would look at the word. I would look at the word. And I would decide: Can this student decode this word? If not, I made the brave decision to just tell them the word. At first it felt like cheating, but this small move, too, changed my teaching last year.

Let me give you an example. The text on the page says, “The fox lives in the woods or in the glen.” The student reads, “The…” and pauses. Her eyes are on the word fox. I know that this second grader has learned all her letter sounds and that if she says the sounds for /f/, /o/, /x/, she can decode this word. So I wait. She looks at me.

“Look at the word,” I remind her.

“The fffffffooooooxx? The fox…” Now she’s stuck on lives. Hmm, this is a tricky one. She hasn’t learned silent-e yet, and even if she had, this silent-e doesn’t make the vowel long!

“Lives,” I tell her.

“Lives,” she repeats. “The fox lives in the….”

Using my knowledge of the decodability of each text combined with my knowledge of our phonics curriculum has changed the way I prompt kids. Kids are more successful, more confident, and actually using word-solving tools to solve words. They are reading.

These two small shifts made a big difference in my teaching. I think about years past when I didn’t realize kids weren’t looking at the word or when I would prompt kids to just “think of a word that makes sense.” I wonder if I did more harm than good, but then I remind myself that when we know better, we do better. I am doing better, and my students are too.