The music starts in our first-grade classroom and kids begin to sign out of their computers, put books away, and select the ones they want to share. Everyone begins to gather in a circle in our meeting area as the music nears an end. Grace sits with her notebook. She’s been busily writing about her reading during workshop. I can tell by the look on her face that she is hoping to share. Parker has a nonfiction book he wants to share with his friends. Paige has an iPad. I had noticed her working at the small table in the corner and am curious about what she is bringing to show her friends.

During our share time at the end of reading workshop, students often bring a response to reading to share with the group. These responses inspire other responses. These responses grow the thinking in our classroom. I wrestle a lot with reader response. In life, readers don’t write about everything they read. Readers read. If they do write, they might write to share or to remember. Sometimes they talk with friends about books. They might jot a few favorite lines in a notebook, record the book title, write a short comment on Facebook, or maybe even write a blog post about the book, but for the most part readers just read.

I’ve never been one to regularly require reader response. For some, reading workshop is a time to do the important work of learning to read, and adding writing can make that trickier. For others, reading is so enjoyable, they don’t want to pause to write. Don’t get me wrong; there are times we write about our reading. Having kids respond to the same text and then sharing responses can help them see the variety of perspectives of readers in a community, think about a book in a new way, and envision possibilities for thinking beyond a text. We are a community of readers, and reading communities talk about books. As Peter Johnston reminds us in Opening Minds, “[Students] understand that knowledge is constructed, that it is influenced by one’s perspective and by different contexts, and that we should expect and value different perspectives because they help to expand our understanding.” Imagine the conversation of possibility from discussing these responses to Monkey Tricks (a Keep Book) by Karl Fieldhouse.

Optional Responses

Over time my students have taught me the importance of choice. As a primary teacher, I know letting go can be hard. There’s a tendency to want to orchestrate the room like a symphonic conductor. Young children who love to play also like to create. Growing options for responding changes the way reader response looks across the year as students learn from friends in the community. Sometimes we write to track our thinking, find questions, discover new insights, or just because we’re inspired to do so.

I always think that one of the challenges of teaching reading is that much of it is invisible work. We infer a lot when we sit beside readers to listen to them read or to talk about their understanding. What strategies are they relying on as they read? What information do they attend to as they read? What are the strengths of the reader? What might be next? Writing about reading helps to make thinking visible, providing a peek into the thinking of the reader. It helps to have opportunities to almost see what they understand. This glimpse into thinking through response can help as I confer with readers and as students set goals for themselves.

My students constantly remind me to let them lead and we will go to better places. Such is the case with reader response. It seems each year I have a core group who love to write about their reading, and they inspire the rest of the class. Here are a few examples of ways students have taught us to respond:

Retelling Response: Students often choose to retell a story. Over the course of the year these retellings will grow as students learn to consider the important details, central messages, and characters in the story.

Skeleton Hiccups by Margery Cuyler: A retelling created in Pixie (view YouTube video here).

Today I Will Fly by Mo Willems: A retelling created in Pixie (view here).

About the Character: Readers enjoy describing characters. In these responses, readers consider a character’s feeling, intent, and action as well as general characteristics. Sometimes students choose to connect characters in a book or across titles. They sometimes talk about how they compare with the characters they read about.

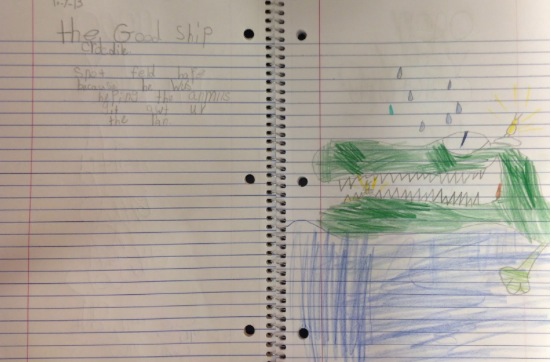

The Good Ship Crocodile by J. Patrick Lewis (author) and Monique Felix (illustrator)

“Snout was happy because he was helping

the animals get out of the rain.”

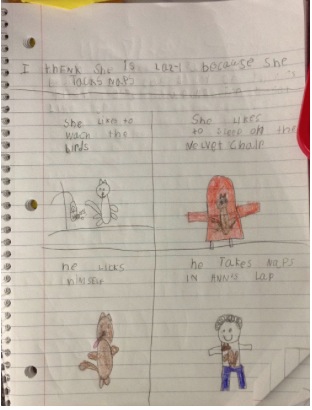

Mugs by Gay Su Pinnell (Keep Book)

Author Message: Across the year as we read we often ask, “What did the author want us to know?” With first graders, it’s interesting to watch this answer evolve from a more literal response to an inferred one.

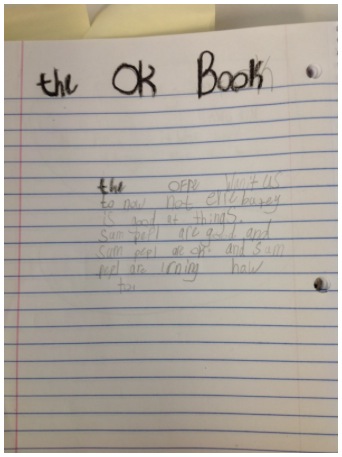

The OK Book by Amy Krouse Rosenthal (author) and Tom Lichtenheld (illustrator)

“The author wanted us to know not everyone is good at things.

Some people are good and some people are ok

and some people are learning how to.”

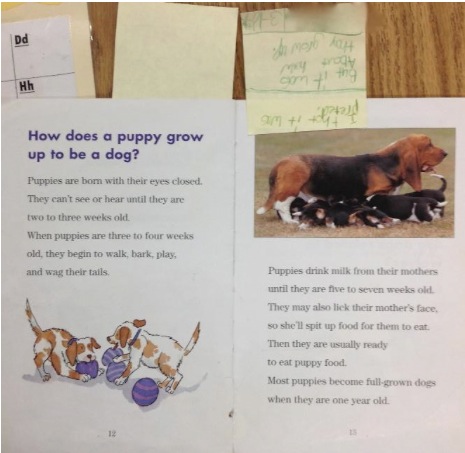

Changing Our Thinking: As we begin to dig deeper into the meaning of text, students begin to recognize places in the text where their thinking changes. In fiction students often make predictions before and during their reading, but the author sometimes takes a story in a different direction. In nonfiction, I find my readers use section headings and pictures to make predictions, but the words often tell them something different from what they expected.

.jpg)

“I thought it was about puppies, but it was about

how many puppies a dog can have.”

This one made me smile. I think this student saw the illustration and thought what she was about to read would be fiction, but then she realized she was reading factual information.

“I thought it was pretend, but it was about how puppies grow up.”

Informational Response: When reading nonfiction, students often like to share interesting things they have learned in books.

Here are responses to reading about bears on Kidblog.

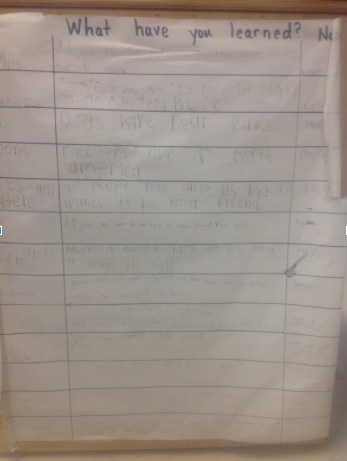

This is a chart Nathan designed so friends could share interesting facts they were learning in nonfiction. He thought it should have a place for the student’s name in case we wanted to ask more about their comment, a section for adding what they learned, and then a place to write the title.

The Power of Ownership

These are just some of the ways students have decided to make their thinking visible in reading, to dig a little deeper. Though I seldom require students to respond, we continually discover possibilities as we notice the ways friends respond as well as the ways people share reading out in the world. Because we share possibilities, children often choose to spend time responding to their reading. It often evolves into the way they work and share in our reading community. Technology has enhanced our ability to respond and to share our thinking with a wider audience. It has, in some ways, forced me to have time in place for students to reflect, create, and share. It has resulted in more student ownership. Most of all, through response, readers have a chance to demonstrate what they know, to think deeply about a text, to share what they’ve discovered with others, and to celebrate the books they’ve read and the authors they love.