Every day at the start of class my coteacher would remind him to take down his hood. He ducked his head inside the hood-cave even farther before reluctantly pulling it down, as if to store up one last burst of protected comfort.

You might know him. He is the student who makes your heart wrestle with the need to reach out and draw him in and the desire to allow him the safety of keeping a wide distance.

Luckily, there is a magic tool that can provide connection and space at the same time.

Poetry.

It was poetry that ultimately prompted Dylan to close the gap between himself and his eighth-grade counterparts.

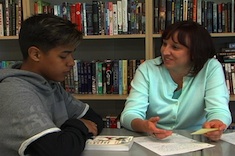

I discovered it one day when I was working with a small group of students who were resistant to writing. We were working on the first in a series of quick-writes to build confidence, stamina, and a quantity of writing that I hoped would eventually lead to a higher quality of writing.

We had read Ralph Fletcher’s “The Good Old Days” and were using it as a springboard into a quick-write. Fletcher describes a single, simple memory from his past. The opening line, “Sometimes I remember the good old days,” and the closing line, “I still can’t imagine anything better than that” beg to be borrowed as bookends to a million other memories.

Dylan was sitting next to me. We had read the poem and were all quietly drafting. Except Dylan. After barely moving his hand across the page, he sighed loudly and slapped his pencil on the table, declaring, “Done!” One glance at the two lines scribbled across the page nearly prompted me to sigh loudly in response. Instead, while he pulled up his hood and rested his head on the table, I worked to keep my head down and continue writing. I thought maybe in the silence, he would consider adding to the two lines about the good old days when he would play video games. No such luck. Yet.

As the rest of the group finished drafting, Manuel asked to share his piece, so I opened the invitation to everyone. He shared a poem about riding a horse in Mexico with his father as a child. Then Cierra spoke up, nervously volunteering to go next. This is where the magic began.

Cierra explained that she had chosen to change the first and last line a bit to match her memory. She began the poem, “I remember the awful days when . . .” and proceeded to describe trying to shield her younger sisters from the brutal reality of her mother’s relationship with an abusive boyfriend. The poem ended more brightly with “I am so glad those days are over now.”

The rest of the group sat in stunned silence before breaking into poetry-inspired snaps of approval. After confirming that she and her family were no longer in danger, I gently thanked Cierra for trusting our group enough to share her poem. I mentioned how proud I was of the group for being such trustworthy writers and heard Dylan mutter something under his breath. When I asked him to speak up, he said, “I want to write another poem. I think I have a better idea after hearing Cierra’s poem. I think I could write about something that really matters to me, like you told us to do. Like Cierra did.”

Dylan’s second draft was about a moment with his stepbrother when he felt like they were “real” brothers. He shared it with the group. With his hood down.

Although this kind of classroom magic cannot be orchestrated, there are deliberate moves that can open the door to invite it inside.

A Teacher Who Writes

Although I am certain my sitting alongside Dylan writing my own piece was not the impetus for his transformation, I do believe it made a difference. By participating in the writing, I positioned myself a little closer to being a member of the group of writers rather than their manager.

Because I was in the midst of my own writing, it was easier to keep my head down and mouth closed when I felt the urge to direct and micromanage Dylan’s initial choice to stop writing after two lines. This silence helped give him the space to form his own conclusion after listening to Cierra’s poem.

It is essential that I create the space for my own writing to sometimes happen alongside students, rather than always presenting a completed piece. I prioritize being fully present when working with small groups or individual students by practicing routines with the whole class to avoid having them disrupt this work. Classroom routines allow me to sit as I write beside student writers.

Inviting Mentor Texts

The next time we got together for a quick-write, Dylan jumped directly into drafting without grumbling. We had read a poem from Scholastic Scope magazine called “What I’m Made Of” by Rebecca Kai Dotlich. It is written in the form of a list of things that make her who she is. We took the invitation and created our own. Here is Dylan’s first draft:

What I’m Made Of (with thanks to Rebecca Kai Dotlich)

by Dylan

Of broken bones that can’t get fixed.

Of not giving up.

And a football and basketball to swish a three or the game winning touchdown.

I am made of anger and aggression, knuckles throbbing.

Of my home and the basketball court and the big waves going onto the beach.

Of rain pouring, bridges to jump from, and home when no one else is there.

Of struggles with school and a phenom at sports.

Of rocks and heat waves and the night.

Poems like Dotlich’s, especially list poems, are open invitations to imitate. Not everyone thinks they can write a poem, but surely even the least confident writer can manage to draft a list. List poems provide a predictable structure and rhythm that allows for line-by-line imitation or simply provides an initial spark writers can use to get started.

Collaboration with Peers

The most important factor in Dylan’s shift toward engaging in writing that is personally relevant was the opportunity to talk and listen to his peers in a small group. The conditions that made the change in Dylan’s approach to writing possible are the conditions that worked for Cierra. If Cierra hadn’t been willing to take a risk, Dylan wouldn’t have been either.

It was Cierra’s bravery and openness that gave Dylan a real-life model of the work he could be doing as a writer. There is power in an audience beyond simply turning in assignments to the teacher. Students working in a small group like this one is one way to make a wider audience possible while maintaining a comfortable distance from students having to expose their work to the whole class.

Here are some of my favorite mentor poems for students:

“What My Name Means” by Jennifer Dignan

“What’s in My Journal” by William Stafford

“I Hear America Singing” by Walt Whitman

“A History of the Pets” by David Huddle

“A History of the Faulty Shoes” by Amanda Granum

“One Boy Told Me” by Naomi Shihab Nye

“Knoxville, Tennessee” by Nikki Giovanni

You might know a hoodie-wearing student just like Dylan. Luckily, you also know the powerful role poetry can play in providing the perfect mix of prompting and room to grow.