The experts will tell you, “Add sand to water, but not water to sand,” when building structures on the beach. You must have a strong foundation for a sculpture that involves super-saturated sand. I know this because I’ve watched my husband and fellow sand men and women compete and carve on the beach. It doesn’t matter if they are sculpting an octopus, gnome, mermaid or six-foot teddy bear, the foundation is key.

Though super-saturated students are not our goal, lesson structure also must have a strong foundation. We have a saying in our coaching team that “good instruction is good instruction,” meaning it doesn’t matter whether we are talking tenth grade American Literature or kindergarten math — the details change, but the components of quality instruction in lessons stay the same.

Lesson Opener: Pound Up

In sand terms, you begin with pound up. Competitors spend time shoveling sand into wooden or plastic forms to create an initial shape. A giant teddy bear would have tiers of forms to fill. About every six inches the sculptors stop and tamp or pack the sand down. Filling a form that’s two feet off the ground is a different experience than propelling buckets of sand up six feet. When the sand is set, sculptors pop the forms and get to work.

A lot of fascinating research has been done on student attention. In a rudimentary summary of a traditional lesson (mostly teacher talking), a learner’s attention is highest at the beginning of a lesson. It then dips lower and lower, and only begins to rise again at the end of the lesson. Lesson openers and closers are important because students are paying attention. The research also shows that we have learning episodes that last about ten minutes. If we stop and do something emotionally relevant (tell a story, show a short video, talk to someone, write), our attention perks up again, ready for another learning episode. Learning episodes for younger students are even shorter. A rule of thumb is to think of attention span equal as to the learner’s age. If you are interested in this research, I’d recommend Dr. John Medina’s book Brain Rules or the video on his website.

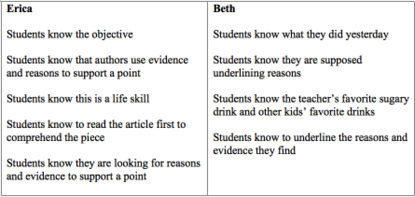

Let’s consider pound up at the beginning of our lesson. Teachers Erica and Beth both spend ten minutes introducing the same lesson. As you read each vignette, think to yourself, “If this is what students will mostly retain, what will they know as a result of this opener?”

Erica opens her lesson by pointing to the learning objective on the white board written as: I will explain how the author uses reasons and evidence to support points in the text. (Common Core RI 4.8) She says, “So let’s think about what we’re going to be focused on? What’s the verb?” Her students respond, “Explain,” as she circles it. “Today we’ll be explaining out loud and in writing. And what exactly are we explaining?” Her students respond, “Reasons and evidence” as she underlines them. “And for what purpose? Ah, here it is: for support. Authors know if they want people to listen to their ideas they need to give reasons and evidence for support. You’ve probably had that experience too if you wanted to stay up later. You might say, ‘I went to bed early last night.’ Which is a reason you are giving to support staying up later. So listen up today, because improving your ability to be persuasive with reasons and evidence to support your point, is an important skill in our world.”

“The article being passed out is about banning sugary drink vending machines from schools, even the teachers’ lounge. That would mean no Cokes after school. I want you to read it the first time through for comprehension of the whole thing. If you have some connections or reactions you can jot those on the sides. During the second read, I want you to underline in pencil the author’s reasons and evidence to support her point about banning drink machines. This isn’t about whether you agree or not, we can talk about that after, but it’s about the reasons and evidence she provides to make her point.” The students get up and move to reading spaces around the room with pencils and begin reading.

Beth opens her lesson by saying, “Who remembers what we did yesterday during reading?” One student volunteers that they’ve been reading nonfiction. The teacher nods. “What else?” Another student says that they were underlining parts of the text. She nods again. “Why were we doing that?” Some students take guesses and finally one says, “To underline the evidence?” The teacher smiles, “That’s right. We are underlining the evidence in the nonfiction text.”

“How many of you drink sugary drinks?” she poses. Hands go up. “I really like Dr. Pepper,” the teacher says. “I like Diet Coke,” says one. “I like Vanilla Crème Soda,” says another. Several kids share their favorite drinks. “Well today we are going to read an article that discusses banning those drinks from schools, even the teachers’ lounge. So I wouldn’t be able to have my Dr. Pepper with lunch. How many of you think we should ban the vending machines?” Some hands go up. “We’ll be underlining the author’s reasons and evidence for banning the drink dispensers.”

Pause for a moment and consider the first ten minutes of attention span. What have the students in Erica’s class focused on?What have the students in Beth’s class focused on?

The difference between the two is that Erica is focused on using reasons and evidence to support points, while Beth is focused on reviewing and sharing. My point is not that we should never review and connect back to the previous lessons or get kids talking about things they like to build interest and excitement. My point is that if we have ten crucial minutes for pound up, for setting the foundation, what is most important for learners? I contend that Erica’s opener offers clarity and focus on learning.

Lesson Episodes: Carving

I’m going to devote a relatively small amount of text to considering what happens in the middle of the lesson: doing the discipline and considering learning episodes.

Doing the discipline means kids are actively engaged in the verb. For example, if my kids want to learn how to carve sand sculptures like their dad, they may watch him set up the forms and help him pound up, but they need lots and lots of carving time. When we say things like “Kids don’t know how to determine importance when they take notes,” then we need to think about giving kids lots and lots of time to determine importance while they take notes.

Thinking back to that attention span research, if kids need to shift about every ten minutes, how can we plan that into our instruction? What would pacing look like?

Minutes/Task

:10 Set objective, purpose, describe the what and how

:10 Students read article and underline reasons and evidence

:10 Students explain reasons and evidence out loud, begin to explain in writing

:10 Students reread article

:10 Students write exit slip on how reasons and evidence were used to make author’s point

Notice how 40 of the 50 minutes students are reading, writing and explaining.

Lesson Closer: Sandscaping with the Primacy-Recency Effect

During the last minutes of a sand competition, tools are everywhere. Big shovels and tampers have been replaced by wedges, specially shaped spoons, cosmetic brushes and a manually powered pneumatic sand blaster (or what most of us laypeople call straws). That’s because it’s time to refine and create those details that make spectators say, “Wow.”

Being intentional at the end of a lesson is challenging. There are many days that I look up at the clock and my carefully crafted conclusion is closed for business because we are out of time. I’m patient with myself, because I know that means I was present and focused on the students. Still, I’m aware of this challenge and I go to great lengths to set timers so that I save the last 5-8 minutes of the lesson.

What do I do during that closure time? I get students actively summarizing, analyzing, evaluating, and reflecting. This might include writing an exit slip, talking with a partner, or jotting notes in a journal. I also know that the brain loves novelty so after a lesson on reasons and evidence for informational text, I might have students choose one of four corners in the room described as: I know how to explain reasons and evidence and could teach it to someone else; I improved today on explaining reasons and evidence; I like explaining reasons and evidence; or I don’t like explaining reasons and evidence.

Closure is two-way because I’m thinking about my 3 M’s:

Who needs More time, resources, scaffolding?

Who has Misconceptions?

Who is ready to Move on?

For the students it’s a time to help them connect to what they just learned and help their brain store that information.

The primacy-recency effect describes our brains’ tendency to remember what we did first and last (or most recent). Interestingly, this fits with the attention span research that shows we’ll remember the beginning of the lesson (primacy) and the end of the lesson (recency). The down-time in the middle is productive, thinking work, but it isn’t captured in memory quite the same way. When we use those closing minutes to pack up, start homework, or lecture to the kids about what they just learned, we lose precious brain time.

What Do You Remember?

Take a moment, cover up this text and think about what you remember. Chances are you remember the sand sculpting analogy, how I started with pound up to make the point about the importance of the setting the foundation and the primacy-recency effect is still with you. If you were to make a list of the things to be thinking about for lesson structure as your closure activity, you might have included:

- Be intentional about opening the lesson, post and discuss the objective

- Within ten minutes give the students an emotionally relevant transition

- Look for students to “do the discipline”

- Consider learning episodes of ten minutes or less, match their brain pacing

- Save five to eight minutes at the end to get kids actively thinking about their learning

- During closure, reflect on the 3Ms: More time? Misconceptions? Move on?

- Then reflect: How solid is the structure of your lesson?