I had been puzzling over Luis for some time. I couldn't get him interested in doing more drawing or writing, and he wasn't like other 3 to 5-year-old children in my Head Start class who were harder to engage in writing and drawing. Usually children who don't draw much have limited small motor skills and find it difficult. Sometimes they are more active by nature and find the sitting still part of writing difficult. Luis did not fit those profiles. He seemed more like someone who wasn't working at his potential. He could easily write all the letter forms neatly, and he has a gentle and patient personality. Nevertheless, he seemed stuck in drawing holiday icons — a pumpkin, a tree, a snowman, a heart.

Day after day, it was the same. If he was encouraged to put people into his drawing, he drew minimalist stick figures. There were no verbal stories that accompanied his drawings as there were even with children who only drew tadpole figures. There were no scribble action lines as in drawings by some children that are totally unrecognizable unless you hear the story. He wasn't interested in trying ideas from his classmates' drawings as many children are.

The most important work I do in the classroom is unseen, and perhaps unrecognized by most: watching the children and noting their interests. What I want is a classroom where children are busy and happy — though "focused," "absorbed," or "engaged" are probably better words because there is a type of busy-ness that is not as productive, when children seem wild or bored. This work is vital because it is when children are actively engaged that they learn (they gain competence and skills). "Interest" or "interesting" is a tricky concept because it might seem like it lies wholly in the activity itself, but I find that it is actually an interplay between the activity and individuals. So every teacher will find that there are some students who are more difficult to get — or keep — engaged.

So, how to interest Luis in writing? Typically I note children's interests simply by watching them and listening to them. In their actions or their words they give a clue. I looked for any little clue with Luis. In drawing, I looked for anything different. And one day, his drawing was different. It was simply a lot of irregular connected shapes. It looked like nothing: not a pumpkin, not a tree . . . It looked like a map! And I made that comment to him. A few weeks later, his drawing was different again. It had a tree, lines for water and a solidly colored space for sand. It was like a small map.

At that point, I definitely wanted to do map work with Luis, and I talked with Ruth Shagoury, a friend and university researcher who has been volunteering in my classroom for the past couple of years. We decided to collaborate on exploring maps and globes with the children, building on Luis's interest and expanding to working with the whole class.

Getting Started

We started with a three-dimensional version of a map. The globe in our classroom is much-loved, but old and out-of-date. Our first step was to get a new-and accurate!-globe that could spin on its axis. (There are also some excellent cheaper inflatable globes that are a good substitute.) We celebrated its newness by opening the box together. As I lifted it out of its package, we heard cries of, "A globe! Awesome!"

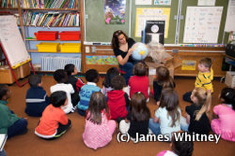

I held the globe out for them to see: "Our globe is old, and some of the countries have changed. So how is the new one different?"

"It's clean!"

"It's shining."

"You can see the writing."

"It's not broken down the middle!"

"You know what's really neat? " I asked them. "I noticed where there's mountains, there's a bump. If I touch very lightly, I can feel it. And you can all touch the globe, too."

I made time for each child to touch the globe, before giving it a place of honor in the classroom — ready for further exploration and engagement. Then, we turned to the books.

Creating Our First Maps

As the Crow Flies: A First Book of Maps by Gail Hartman, illustrated by Harvey Stevenson is a perfect first book of maps. Readers see several animals' worlds, and the maps that show these places from their points of view. I read this book to them slowly, allowing them to comment and make connections to the globe. Then, we had a chance to do some playful explorations with maps.

I invited the children to choose one of our stuffed animals and create a habitat for that animal. They could use blocks, toys, some stones I had brought in — whatever they wanted to engage in imaginative play creating their animal's world. "So, if you chose the turtle," I asked the children, "what do you want for him to live in?"

"Rocks," suggested Kevin.

"He needs water," Lacey added.

"Yes, those are wonderful ideas. Make your place for your animal, and when you are done, you can make a map of it, just like in the book."

The children enjoyed their imaginative play — and their animals' maps. In the pictures below, you catch a glimpse of their creations, and their beginning understanding of showing a three-dimensional world on a flat piece of paper. We'll continue to work with the other map books, and create more of our own.

It will come as no surprise that there was a lot of problem-solving, including mathematical thinking, social language, and imaginative language as we work on our maps. Just as I had hoped, this project was just the spark that Luis needed to move forward. He's much more interested in writing, and he has a look of pride about his work. He's doing new and different things — and noticing when other children get their ideas from him! Searching for his engagement, I found new connections for the whole classroom.

Books for Introducing Grades PreK – 2 Students to Maps and Globes

The following four books are especially good introductions to maps. Best of all, they inspire children to pick up crayons, pens, and paints to create their own maps.

As the Crow Flies: A First Book of Maps by Gail Hartman, illustrated by Harvey Stevenson

What kind of maps does a rabbit use? Or a crow, an eagle, a horse, or a seagull? Readers follow along each animal as they show their "favorite" ways to go. This book serves as a wonderful introduction to basic maps and mapping. We see the world from each creature's point of view, as well the key landmarks in their world. The illustrations are clear and inviting. A perfect first book of maps!

Me on the Map by Joan Sweeney, illustrated by Annette Cable

Me on the Map is another simple book to introduce children to the idea of maps. The nameless little girl who narrates the book shows herself in her bedroom, then creates a simple map to illustrate herself in her room. From there, she expands to her neighborhood, city, state, country, and world. One mom we know used this book and the mapping activities it inspires to teach her son their address.

Mapping Penny's World by Loreen Leedy

Lisa also begins her mapping in her bedroom. She includes everything in her room: all the furniture and even her Boston terrier, Penny. She decides it would be fun to map Penny's world as well as her own. Lisa explores Penny's journeys and as she does, she explains the tools she uses to make the maps. She needs keys and symbols as she looks at her familiar world from a different perspective. The maps are very simple and uncluttered, making them a wonderful guide for children to use as they create their own maps.

My Map Book by Sara Fanelli

You can create maps of anything, like a map of your tummy, your heart, your dog or your day! In Sara Fanelli's bold, bright, and colorful book, you can search for and interact with each map. While there is no story, the book simply invites you to explore the pages, poring over the details and imagining new possibilities for maps. Children love to create their own maps after reading this book — especially the maps of their own hearts.