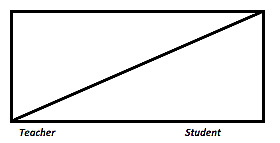

Do you remember where you were when you first saw the (now familiar) scaffolding diagram? Oh, come on. You know the one.  The long rectangle with a diagonal line stretching from the top right corner to the bottom left dividing it in two? On the far left hand side was the word teacher and on the far right was the word student? Remember?

The long rectangle with a diagonal line stretching from the top right corner to the bottom left dividing it in two? On the far left hand side was the word teacher and on the far right was the word student? Remember?

I do. I was in our small campus library sitting at a child-sized study table around which sat our assistant principal, me, and the rest of my grade-level team. And I was overwhelmed. You wouldn’t think that such a basic looking diagram could get me all worked up, but it did. I was suspicious. Looking at it, you’d think scaffolding was a fairly simple, straightforward concept. But somewhere deep inside me, I knew better. And as our balanced literacy trainer’s voice echoed my concerns, I knew I’d be spending a lot of time getting to know this rectangle.

Over ten years later, as I’ve moved from classroom teacher to Reading Recovery teacher to literacy coach, I’ve seen that diagram and its many variations more times than I can count. No matter how many times I encounter it, its simplicity still remains a bit deceptive. Oh, don’t get me wrong. It’s a helpful visual, but scaffolding our instruction is anything but simple, requiring skillful teaching moves based on thoughtful interpretations of all the various information we can gather on our students. It can be even more difficult to build scaffolds for the students who need our intense instruction the most – those struggling and reluctant readers we encounter on a daily basis.

True scaffolding takes an in-depth knowledge of readers as well as the instructional practices that will most benefit them, and it involves a seamless, almost art-like dance to the beats of varying levels of support. A dance that is different for each student, and one where the steps can change based on the needs of the reader and the focus of the instruction.

As instructors, we take the lead in this dance, determined that our readers will eventually move to the captivating melodies of reading and writing – on their own and without our guidance. But we move cautiously. We know that too many missteps or leading too much will create readers who can’t dance on their own or worse, don’t want to dance at all.

In all of this, we continue to sharpen our skills as instructors. We continue to learn. We continue to grow.

Simple? I think not.

Rescuing: Scaffolding’s Evil Twin Brother

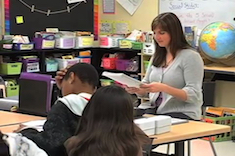

Recently I had a chance to work for several weeks with a group of teachers who were eager to take a good, strong look at their teaching practices. I asked them to identify four students for daily individual tutoring just after school let out for the summer. In addition to coaching them during their individual tutoring sessions, I offered to design an ongoing staff development program to support their instructional goals. During the planning stages, the teachers asked that we spend time investigating their use of language to support their students’ sense of agency.

I asked teachers to record their lessons and transcribe them for the group. During our staff development time each day, one of the teachers would share a transcript of a lesson, and we would look at the way she used language to support her student in moving toward independence.

As we investigated their instruction, I began to notice a recurring pattern. The group seemed to have a desperate need for their students to do well. Why wouldn’t they? Isn’t that the crux of a powerful lesson: to cater our book introductions and scaffolds in such a way that the reading – and the reader, as a result – is successful? But it seemed to run deeper than that. They definitely had a sense of urgency for their readers to get it right – however, the problem was that many of their readers didn’t seem to share that same sense of urgency. The teachers were working harder than their students were. In some instances, they were doing almost all the work. This sent up a red flag and I decided we needed to take a closer look at the origins of their instructional decisions.

Returning to our original line of inquiry, we started to look at their use of language and our understanding of student agency. As we reviewed lesson transcripts and our instructional decisions, we noticed an overall pattern of teaching that included an impulsive need to sweep in and help at the slightest moment of difficulty. Sound familiar?

When I asked the group to their interpretations of this pattern, some initially reasoned that they were working within the zone of proximal development, some wondered if maybe they were jumping in too soon, and a few admitted that they really weren’t sure why we were teaching this way.

I returned to that familiar scaffolding diagram and asked them to think about where they were on the scale of support during these moments. We had a lot of conversation around what it means to scaffold our instruction. In these conversations, we realized that when our scaffolds aren’t strong and our students start to falter as a result, we tend to grab at straws instructionally – desperately trying whatever we can to “save the lesson”. We wanted our readers to feel successful, but at the moments they weren’t, fear and uncertainty had us jumping in (often too soon), taking over for the reader, and carrying the weight of the work at hand.

Eventually we came to recognize this behavior as rescuing, and dedicated the rest of our staff development time to investigating how rescuing occurs, how to differentiate it from scaffolding, and how to adjust our instructional techniques to prevent it.

When Rescuing Isn’t Helping

There is certainly a fine line between scaffolding and rescuing, and in many ways, their similarities can be confusing. It’s an easy mistake, because when you think about it, both rescuing and scaffolding stem from a foundation of collaboration and assistance. Both are helping behaviors. Both scenarios denote a more capable person (the teacher) supporting a needier individual (the learner).

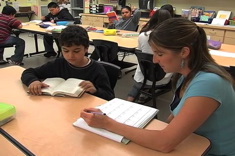

Despite these connections, rescuing and scaffolding can often be polar opposites. In our work, we learned to differentiate the two by reflecting on one overarching concept: agency. I often ask teachers, “Who do you think worked harder during that lesson – you or the student?” In a rescuing situation, the teacher is generally the only one working – the sole responsibility is placed on the rescuer. On the other hand, when scaffolds are built into the instructional plan, the student is working just as hard as the teacher (if not harder) as the teacher assumes a facilitative role – supporting, modeling, and encouraging. But not taking over the reader’s work at hand. In essence, scaffolders offer just the right amount of support to make it easy to learn. Scaffolding requires a shared responsibility with an end goal in mind. Rescuers simply take over.

The Rescued

Whether conscious or unconscious, rescuers envision a learner who is helpless – someone who can’t do it on his own or is simply unable to pull himself out of whatever it is that is got him bogged down in the first place. While it can happen with just about any student in any situation, it appears to occur most often when working with struggling readers, unmotivated readers, ELL students, and any of our ‘harder to teach’ learners. Since many teachers don’t want to risk pushing these readers even further away, they may feel reluctant or uncertain as they raise the bar for them. Additionally, since many of these struggling readers often come to us with a sense of learned helplessness, both teacher and student seem primed for a rescue scenario to unfold. In reality, as these are exactly the students who need our intentionally scaffolded focus the most. Instructional rescuing is often counterproductive and may even be detrimental. In a classic case of best intentions, our readers grow accustomed to our rescuing behaviors and learn that if they wait long enough, someone will eventually feel sorry for them and jump in to do the work for them.

The Rescuers

Teachers are essentially helpers and any one of us might don our rescuing cape at different times. It comes with the territory. But it’s one of those traits where less is more. While I agree that there are teachers out there who are chronic rescuers, rescuing isn’t a full-time sport for most teachers. It really is about looking at our own instruction and simply noticing our tendencies. Some teachers tend to rescue more with needier readers, while others might rescue more when their overall energy is low or they’re having a bad day. We may rescue when we’re uncomfortable with a particular area of instruction or we haven’t planned our lessons as well as we’d like. Some teachers rescue randomly based on the perceived needs of students in a particular instructional moment, while still others rescue out of a need to feel effective.

Rescuing appears to happen most when we don’t have a strong plan for the scaffold in place or when we skip a step in the scaffolding process. When we’ve left learners high and dry without any support system, it looks like they need rescuing. For example, I’ve noticed a common situation where teachers are left to feel that we’ve no choice but to rescue – and it’s one we often set ourselves up for. Consider one of the fundamental progressions of scaffolding which, in its most basic form, involves the following continuum of instructional steps:

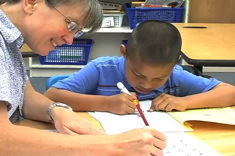

1. I Do/You Watch – teacher models the task and the student observes

2. I Do/You Help – teacher does the majority of the work while the student helps

3. You Do/I Help – student does the majority of the work while the teacher helps

4. You Do/I Watch – student does the task while the teacher observes

When navigated correctly, moving through this instructional sequence produces incredible results. However, I’ve noticed that some teachers skip Steps 2 and 3 and in doing so, create a situation that is ripe for rescuing behaviors. Still others might redefine Step 1 as simply “I tell you about it/You listen” and then continue directly to Step 4. These oversights are generally unintentional and teachers are often unaware they even happened. Yet consider how directly related they can be to situations where readers start to drown and need a life boat.

Scaffolding vs. Rescuing: Analyze Your Behavior

I’ve developed a couple tools to help you gauge if you are putting up scaffolds or performing rescues with specific students. The first is a compare and contrast chart of scaffold and rescue behaviors. You can download the chart by clicking here.

The second tool is a self-test to assess how you interact with students.

Consider your small group and individual reading instruction. If you answer “yes” to more than just a few of these questions, it may be time to take a closer look at your rescuing behaviors:

1. Do you often find the momentum of your lesson waning without a good reason?

While there are plenty of other variables that may be at the root of this problem, rescuing is one you might consider. It isn’t unusual for a rescuer’s lesson to start out with a bang and then wind down to a fizzle by the end. I’ve noticed this problem to be twofold: the teacher tires from ‘dragging the student along’ and the reader tires from the boredom of having to sit through the lesson.

2. Do you find yourself physically holding the text, turning the pages, and pointing to difficult parts as your reader(s) sits back, physically uninvolved?

While there are certainly times where these teaching behaviors are necessary, they are fewer than most of us would like to think. Rescuers have a difficulty ‘pushing back’ from the table and letting the reader give it a try on her own.

3. Are you exhausted after a lesson?

As a result of taking on most of the responsibility around the learning, teachers who rescue often work harder than their students, leaving them utterly exhausted, despite having started out fairly energized.

4. Are you doing most of the talking?

Rescuers tend to take over conversations with students. This can be a sign that they are doing the majority of the work, so the reader doesn’t have to.

5. Do you avoid challenging students for fear of where that challenge might take you?

As a defense mechanism, rescuers often want the lesson to flow smoothly, so they avoid sticky situations at all costs. They especially tend to steer clear of ambiguous situations where they can’t control the outcome. In this way, they’re preemptive – avoiding situations where the reader would even need to be rescued at all.

6. Is it difficult for you to allow students to work through a challenging text on their own? Could your wait time be extended?

Many rescuers jump in entirely too soon. And when they do, they generally take on the work themselves. If too much time has gone by, consider jumpstarting the stall with a decisive, well-placed prompt such as: “I see you’re stuck there. What could you do to help yourself?”

7. Do you struggle to take notes on student reading behaviors?

Though not always indicative of a rescuer, it may be the reason you can’t take good instructional notes is due to the fact that you’re too busy doing the reader’s work for him and your hands are all over the text.

8. Do you generally ask closed questions?

Closed questions usually require a one-word answer without a lot of thinking. They are a common form of rescuing, because they give the illusion that both the teacher and the student are successful. For example, Did you like the character? vs. What can you tell me about the character? is the kind of questioning shift you might try.

9. Do you machine-gun students with follow-up questions, not allowing time to really share their thinking?

This is a frequent rescue behavior. I’ve seen many teachers who will risk an open-ended question only to follow it up all too quickly with an onslaught of rapid-fire closed questions. There is discomfort with the silence the student’s thinking time invokes.

10. Do you struggle to define a focal point for your lesson, teach many lessons “on the fly,” or have difficulty keeping the lesson focused?

Even though it may ‘all seem important’, we can’t teach everything at once. Without a focus, our lessons can feel scattered, leaving us feeling unprepared. And when we’re unprepared, we tend to rescue more. Choosing an overarching focus supports teaching that is more deliberate in its scaffolding.

Deliberately planned and intentionally executed scaffolding is the antithesis of instructional rescuing. Often, readers who appear to need rescuing actually need a stronger scaffold. It takes intentional planning on our part, not to mention lots of practice, but the first step is awareness. When we take a moment to investigate our instruction with an eye toward screening for rescuing behaviors, we are making powerful movements toward helping our students become independent lifelong learners.