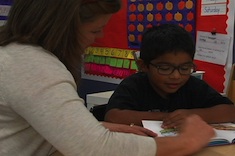

It was late fall, and I was sitting in our reading reflection circle listening to my students share their thinking with the group.

“I read 35 pages,” said Luke.

Not to be outdone, Shreya chimed in with “I read eight books.”

“I read this whole book,” said a beginning-level reader, holding up a Junie B. Jones title.

Other students began sharing the amount they had read during our reading workshop that day. A few others chimed in with certain word patterns they had noticed in their reading, and that was about it for that day’s reflection circle.

I usually respond to each student with follow-up questions, but on that day I felt too shocked and, frankly, disappointed to do so. As I reflected later that afternoon, I couldn’t help but wonder where I had gone wrong. How was it that my students thought I valued quantity and speed over real thinking? After a multitude of lessons on reading as thinking, how was it that their responses to our reading time were about the surface of what they were doing as readers? I had set up my reading workshop with the same routines and lessons as previous years, yet the experience at our reflection circle told me that I hadn’t met the needs of this particular class. I had to find another way to teach what I wanted them to do while reading. I had to teach the thinking work that I expected more explicitly.

I decided to backtrack. I had just started our series study and was using the Stella and Sam series by Marie-Louise Gay to draw out features of series books. We had read Stella, Queen of the Snow the previous day, and I had stopped to share and talk throughout the story as I usually do during a read-aloud. I decided to revisit that read-aloud during our lesson the next day.

Beginning Again with Reflection

When I pulled out the text, I asked students to remember the fun I had had reading this story aloud to them. They quickly remembered and nodded in agreement that together we had loved the book. I told them I was going to read it again and make the same stops and comments as I read. Their job was to notice where I stopped and what I talked about as I read Stella, Queen of the Snow. “When I am finished reading, let’s share what you saw and heard, and we’ll make a chart of your observations.”

I read the book and did my best to stop at all the same places as the previous day. When Sam looks out at the snow for the first time, I paused to reminisce about when we had had a snowstorm nine years earlier and how I had gotten Andrew out of his crib and he’d stared out the window, studying the world outside our house. When Sam and Stella walk outside, I paused and wondered what activities Stella and Sam will do in the snow. And when Sam asks, “Why is fog coming out of my mouth?” I laughed and tried to guess how Stella will cleverly answer his question this time. I paused at Stella’s response that birds wear snow boots and commented on how clever she is and how I wished I could think like she did.

And when the story was over, I closed the book and paused. I turned back to some of my favorite pages, reread them, and laughed or smiled, then turned to the cover and talked about all the things that I love about this book and these characters. I included some wonderings and hopes about other Stella books.

I then looked at my class and asked what they had noticed about my reading.

“You were thinking!” a student yelled out. I knew this response was imitating what I often tell my class. I was hoping that they would notice more.

“Yes,” I said. “I was thinking, but how could you tell?”

“You were remembering when Andrew saw snow for the first time when he was little.”

“Yes,” I said. “Let’s add ‘remembering’ to our class chart.”

“You were laughing.”

“Yes, let’s add that to the chart.”

“You were taking your time, going back to certain pages.”

“You were wondering what Sam would ask next.”

Before I knew it, we had a chart of reading strategies that the class had come up with by watching me, a reader, carefully. I ended the lesson by reading down our list, telling the class that all that work I did as I read Stella, Queen of the Snow was real reading. It didn’t matter how many pages were in the book, how quickly I read it, or how many books I read after that one. What was important was that during and after I read it, I was connecting, predicting, wondering, imagining, and more. I noted that it was easy to put I’m in front of any of the words on the chart to guide our thinking and sharing and had students practice with a partner next to them. Then I sent my students off to their own independent reading with the chart as a reference and a sticky note to record some of their own thinking from their reading that day.

This lesson and chart guided my class for the rest of the year. It guided my instruction and became a reference point for my students to share their own thinking in our reflection circle and during partner and small-group time. We referred to the chart to ground us when our thinking became focused on the surface structures of reading. Our reading improved as demonstrated by the shares during reflection circle: “Today when I was reading ___________, I was wondering _______________. And when _________ happened, I was surprised.”

Listening to these shares told me that the thinking my students were doing was improving and that we were on our way to thoughtful reading!