When students enter my high school English classroom and see the bins of colored pencils and markers out, many are excited, but there are always a few who give me the side eye. They want to know why I am making them draw in an advanced English class. And I’m happy to answer them, because although I do like to include “fun” activities in my classes, I also want to make sure these activities advance my students’ learning or comprehension of a text. With so much to accomplish in English class, I don’t want to waste my time or my students’ time on work that doesn’t serve us both. Here are three ways that I have incorporated drawing into my classroom that are useful to students.

Illustrated Timeline

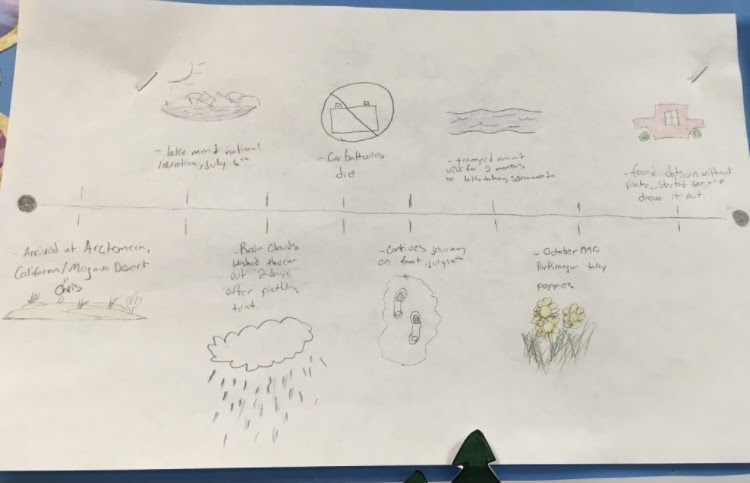

Drawing can help a learner synthesize information, which can be useful in a text with an interrupted or confusing timeline. For instance, the book Into the Wild contains a lot of information about the travels of Chris McCandless that is difficult for students to remember. I assign sections of the text for students to take notes on the major events, places, and people who influenced McCandless’s life. Afterward, students create a picture to symbolize each event and then arrange the pictures in a timeline.

Students are not only spending more time with the text and finding specific details and evidence, but also thinking symbolically about these details through the creation of their drawings. We hang these illustrated timelines on the wall, and they serve as a reference to think more deeply about McCandless’s life and death at the end of the book.

Cartoon Sequence

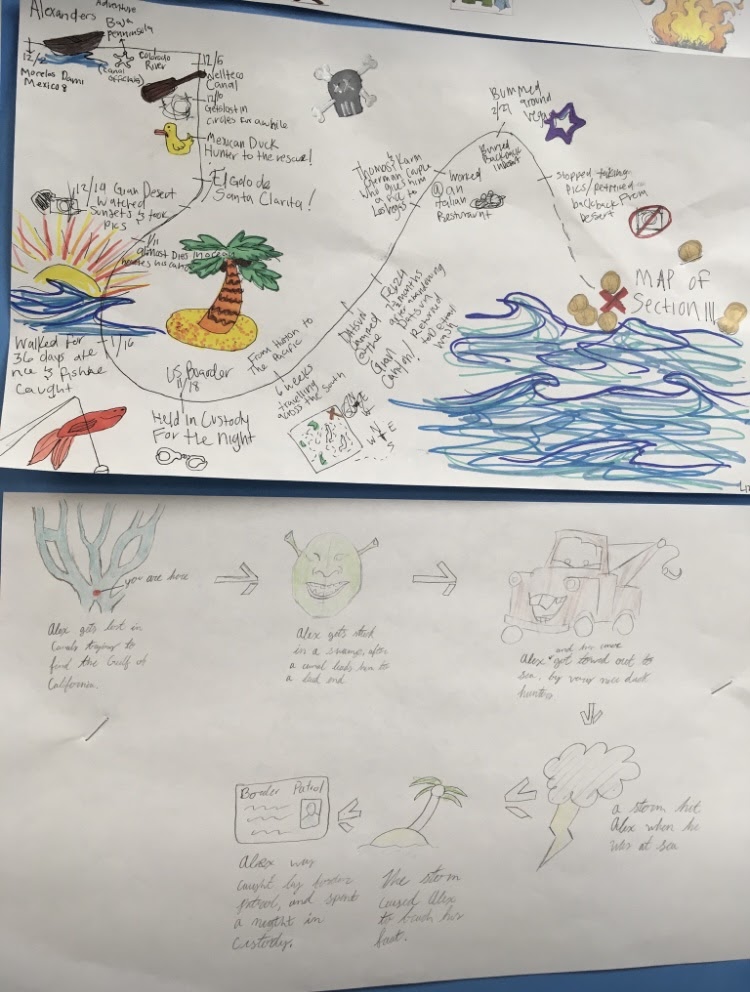

Sometimes when reading a novel, students rush through important scenes and miss small but important details. Again, asking students to slow down and incorporate drawing allows them more time to process the text.

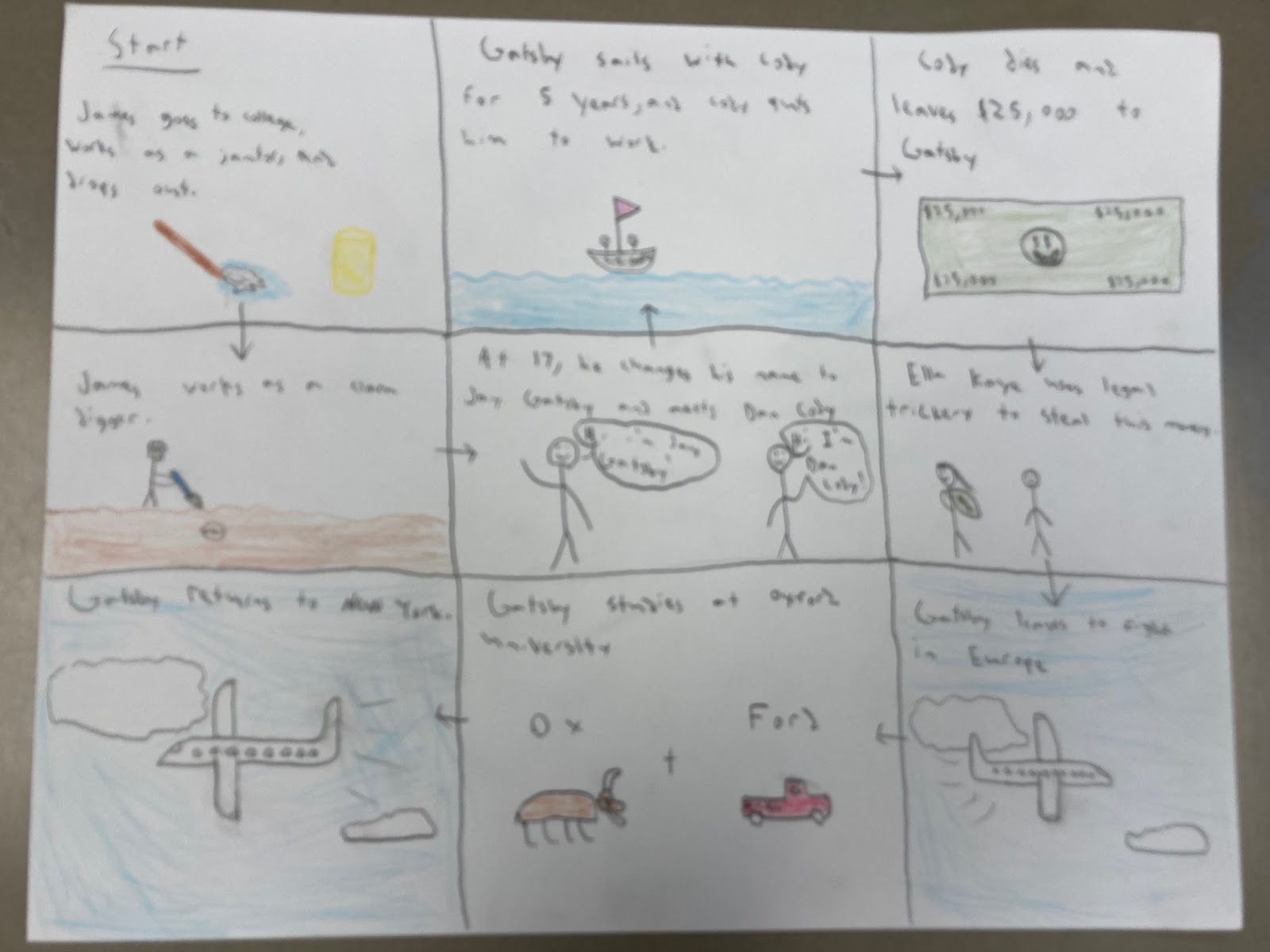

A lot happens in the last two chapters of The Great Gatsby. In the face of some shocking arguments and deaths, several smaller yet significant events go unnoticed by my students. I ask them to go back to a section of the text and create a six-panel cartoon sequence of what they consider the six most pivotal moments in that section of the novel. Students must weigh each event carefully and then visualize to consider how to represent the event in a sketch. When students return to class, it is always interesting to see the different choices they’ve made. We share as a class, and students can defend their choices, considering why their event was important when we look at the book as a whole, which leads to deeper discussions of theme and author’s purpose.

Word Art

Word Art

Studies have shown that drawing is an effective way to boost memory, some even going so far as to say that drawing is twice as effective as traditional note taking. When we began a unit on Gothic literature, I wanted students to be familiar with the elements of the genre, such as the supernatural, confinement, social upheaval, doubles, and hero-villains, so that they could then evaluate the texts in the unit. I gave them access to several videos and articles as source material, and then they artistically displayed the elements of the genre through word art, where each letter symbolically represents an element of the genre.

In the example below, Holly’s G is a man overpowering a woman, which represents how male dominance and women in distress are common elements in the genre. Her O is a rock to represent the common feature of barren landscapes. Here, too, we shared these in class to see what each student came up with and then displayed them on the wall for reference

Some students who are artistically inclined will put a lot of effort into these types of assignments, but I always remind them that they are being assessed on their thinking rather than on their artistic abilities. I want them to use drawing as a means to an end, and not have it be the end itself. This is also an important reminder for students who aren’t good at drawing (myself included!). A cartoon sequence doesn’t need to be a masterpiece to have helped students make sense of a text or show understanding of a concept.

In the end, it is important to share the purpose of these assignments with students up front, so they can see how drawing can be a tool to help them rather than just a fluff assignment to pass the time. One Friday in May, while students uncovered the details of Gatsby’s coming of age through an illustrated timeline, I heard Jacob make a snide comment to his table partner about working on his “art project.” Being somewhat immune to teenage snark at this point in my career, I good-naturedly asked him if he had caught all the details of Gatsby’s young life on his first reading of the chapter. He paused for a second and then replied, “Actually, no. I kind of skimmed over that part.” We both smiled, and he got back to work. A couple of weeks later, Jacob used these same details in his final essay, so I think we both knew that the work was not done in vain.