If I walk out of my classroom during class changes, the hallways is abuzz with chatter and conversation. I observe intimate powwows in front of lockers and hasty discussions down the hallways, with a few shouted jokes and reminders peppered amongst them. And, if I head into the lunchroom, the sound of talk is nearly deafening: a veritable gabfest that reaches a crescendo as students finish eating. So why is it that when I give students the opportunity to talk and discuss in class, I’m often met with awkward silence? The lively tete-a-tetes are replaced by those cliched crickets. Below are some of the most common problems I encounter when it comes to small-group and whole-class discussions, as well as some of the solutions that have worked for me in combatting them.

Problem

You place students in small groups to discuss, but they don’t talk or, if they do, they don’t listen well to one another.

Solution

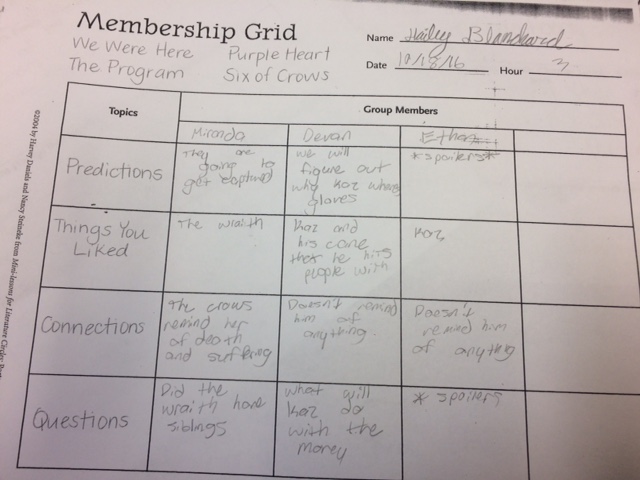

There always seems to be at least one group in a class that has a difficult time getting discussion started. Even the most well-crafted discussion prompts or activities cannot get them talking. They seem content to just sit in defiant silence, hoping you won’t notice them. I have found that often what these groups need is accountability. Years ago, I came across the idea of using a Membership Grid in Minilessons for Literature Circles by Harvey Daniels and Nancy Steineke. Students put the names of their group members along the top of the grid, and the discussion topics or questions down the far left column. When we’re discussing a book, common topics we will put on the grid are predictions, likes or dislikes, connections, and questions (see picture). The grid requires students to listen and take notes on what each group member says, and, on the flip side, each student must speak in order for the grid to be filled out completely. Having the completion of the grid as a goal of the discussion is enough incentive to get my most reluctant speakers adding to the conversation.

There always seems to be at least one group in a class that has a difficult time getting discussion started. Even the most well-crafted discussion prompts or activities cannot get them talking. They seem content to just sit in defiant silence, hoping you won’t notice them. I have found that often what these groups need is accountability. Years ago, I came across the idea of using a Membership Grid in Minilessons for Literature Circles by Harvey Daniels and Nancy Steineke. Students put the names of their group members along the top of the grid, and the discussion topics or questions down the far left column. When we’re discussing a book, common topics we will put on the grid are predictions, likes or dislikes, connections, and questions (see picture). The grid requires students to listen and take notes on what each group member says, and, on the flip side, each student must speak in order for the grid to be filled out completely. Having the completion of the grid as a goal of the discussion is enough incentive to get my most reluctant speakers adding to the conversation.

Admittedly, the conversation can be somewhat stilted and mechanical when using the Membership Grid, but if the alternative is no one speaking up, I’ll take it. Initially, that is. I find that the Membership Grid is necessary only for the first few discussions. It seems that after that, students are more comfortable talking with their group members, and filling out the grid becomes more of a hindrance to the discussion. In a class, some groups will never need the Membership Grid to get a discussion going, whereas others may need it longer. I try to use it as a tool to help quiet groups get going and then take it away when I think the group no longer needs the accountability of filling it out.

Problem

You want to conduct a whole-class discussion, but no one speaks up or only the same handful of students do, and the dynamic discussion you were hoping for quickly peters out.

Solution

To counteract a boring or sluggish whole-class discussion, get students out of their seats and moving around. It’s easier for students to be passive during a discussion when they’re sitting slumped in a desk, but there are two discussion activities that I use that get every student sharing his or her opinion. The first activity involves a line, which I create across the classroom floor with some masking tape. As I read controversial statements pertaining to a piece of literature, students have the choice of moving to one end of the line if they agree with the statement or to the other end of the line if they disagree with the statement. Students also have the option of standing in the middle of the line if they are “on the fence” or unsure of whether they agree or disagree. For example, while reading Frankenstein, one statement might be “Victor is responsible for the death of Elizabeth.” Students from each side of the line then offer up their thoughts, ideas, and evidence from the text to explain their opinions. Sometimes students will choose the middle because they think it will exempt them voicing their opinion, but the caveat is that the people in the middle must then choose a side and explain which piece of evidence from their classmates was the most persuasive.

Another activity that gets students up and moving around involves dividing the classroom into quadrants (again, some masking tape gets the job done). Each quadrant has its own sign indicating two qualities. For example, to discuss the characters in Frankenstein, I would have the following quadrants: Good/Gets what he or she deserves; Good/Doesn’t get what he or she deserves; Bad/Gets what he or she deserves; Bad/Doesn’t get what he or she deserves. I would then call out the names of different characters in the novel, such as Victor and the Creature, and students would move to the quadrant that best described their assessment of the character. Once all students are in place, students in each quadrant can provide examples from the novel to back up their choices. In both activities, even if individual students don’t offer an opinion vocally, they are still sharing their opinion with the class through their movements.

When classroom discussions go well, they can be magical experiences. Knowing the wonderful possibilities of a great discussion can tend to leave teachers with high expectations. But it is important to remember that a “bad” classroom discussion doesn’t have to be chalked to being a waste of time. Rather, those discussions can help us and our students explore what went wrong and what can be done differently. Oftentimes, the solution is simpler than we think.