The Dewey Decimal System is an organizer’s dream for placing an expanding supply of informational texts into a library, a way to help readers find what they need with the least amount of effort. I heard a wonderful school librarian explain to my class that Dewey’s code creates a map to finding good books and information treasures in the media center. For me, the Dewey system is about efficiency. If I want a book on housebreaking a puppy, the art of Monet, or the history of the printing press, the Dewey Code can get me what I need in the least amount of time. The Dewey Decimal System is comforting, like the signs that mark each mammoth aisle at Lowe’s or Home Depot when I am sent on a quest to find a small but important L-shaped plumbing fixture for an under-the sink repair. “Yes, ma’am, that would be Aisle 6, just about six shelf units down.” I like those simple directions. I like it even better when the employee says, “Here, let me show you just what you need” and I trail after him, accepting with an outstretched hand that plumbing piece that lets me leave and be on my way. Comfortable and efficient: two appropriate ways to describe a school or public library.

How do teachers start to wrestle with the idea of organization in our classroom libraries? Does this mean we need to start coding our informational books into an organizational system of categories and subcategories with tidy, predetermined number codes? I’ve spent many years developing an informational library that I thought appealed to children. I thought I had my own organizational system in place without the need for Dewey’s system, and I was pleased with the evolution of my library. Scanning my room I had bookshelves designated for domains such as Life Science, Earth Science, and Physical Science. On those shelves sat carefully labeled tubs such as Birds, Weather, and Transportation. In another area of the room, shelves housed resources about our cultural world. Biographies were sorted alphabetically by the famous person’s last name on a tall bookcase. Books and maps about other countries were alphabetically placed on labeled shelves. Nice and tidy. Easy to manage. I was faced with a problem, and something was missing. . . .

In my efforts to organize my growing collection of books and make locating and reshelving resources easier, I forgot a major element: the kids. They were not browsing the shelves with the same attitude they had when they shopped my fiction and poetry areas. I started watching my students, and they consistently delivered a disheartening fact: very few of them independently explored our nonfiction shelves unless I was leading them along like a helpful sales associate at Lowe’s. They did not act like me drifting through a local nursery, marveling at plants, in love with the colors, and imagining their potential for making my home beautiful. My students were not browsing with that interested slowness created by captivating book shopping. Watching my dedicated informational readers, I realized they were acting like me in an overwhelming home improvement store, a Special Forces officer on a mission to search, locate, and get out. I had worked hard to make our nonfiction library organized, but I had overlooked an important point. I wanted book browsers, like admiring shoppers, discovering and cradling those wonderful books in their hands; I wanted them to feel that curious potential I discovered when I found and purchased those books to share with students. I knew something was missing. I knew that my nonfiction library was filled with amazing and beautiful texts. Why were my kids not discovering these treasures?

Matching Beliefs and Organization

I wrestled with this “problem” of too many books and not enough readers. First I considered my beliefs about creating a learning environment for children. I believe a classroom library and its organization are critical; some say that the environment and its design are the third teacher in the room. I believe that organizing my library means giving my nonfiction resources as much attention as my fiction and poetry collections. I firmly believe that how I organize my informational texts plays a big role in how my students develop and enrich their nonfiction reading lives. This is when my honest reflection presented prickly results; it was time to get honest because I thought my nonfiction books were highly visible, but why were they underused? My kids were not browsing for informational texts, and thus they were not selecting enough books from our library. It was that simple. I considered my next steps.

The learning community begins, revolves around, and ends with children, so I figured students would be most helpful in my quest for my library problem and its circulation solutions. Starting with positive information, I decided to interview my consistent nonfiction readers first and find out what attracted them to the nonfiction choices in our library. I asked this set of questions:

-

Why do certain nonfiction book tubs attract your attention?

-

Why do you avoid or ignore areas of the nonfiction library?

-

What could we do to increase traffic and interest in the nonfiction library?

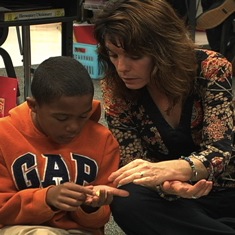

I started with my avid nonfiction readers, Sarah and Trey. Sarah, a geography buff, loved to read about other countries. Trey, resident animal lover and specifically big-cats expert, had completed several extended studies about lions, cheetahs, leopards, and mountain lions over several months. When I looked over their reading logs, it was easy to see that their restricted browsing habits had limited their reading choices to very specific bookshelves and book tubs. Beyond their favorite topics, they had overlooked a majority of the library’s options. I scheduled a conference with them and wanted to know why they did not select a wider variety of nonfiction books from our classroom library. I shared my questions with them.

Their answers presented eyebrow-lifting conclusions. “I like to read about countries. I walk past the animal shelves all the time, but I’ve never thought about studying any animals . . . like birds,” said Sarah, dragging over a huge, heavy tub. “I think this tub is packed with too many books, and I don’t know how it would help me with a topic I’ve never studied before.”

“I love learning about animals,” Trey said. “You know how I’ve studied big cats? Well, I never thought about using this African Animals tub because it is too big . . . too many books to choose from. But when you talked to me about what I wanted to study and you pulled out all the big-cats books from this tub and some other tubs and made a new tub called Hunting with Big Cats, then I knew exactly where I could find books that interested me. I started off thinking only about lions, and then I stayed with that tub because you got me thinking.”

“I’m thinking about visiting this tub,” Sarah said as she presented a smaller basket and showed me the label: Backyard Neighbors: Our Feathered Friends. “You know how we are going to feed the birds this winter and then how we will track the arrival of robins in the spring? This tub helped me get interested in reading the books. You started this tub because of our class project, and I know how this tub could help me. This giant bird tub . . . I am not so sure. This smaller tub made me want to dig in and learn more about birds.”

“What makes this bird tub marked Backyard Neighbors: Our Feathered Friends more interesting?” I asked.

“The giant Birds tub makes you think of a boring collection of reference books,” Sarah said. “I didn’t even think to dig through it at first, but the Backyard Neighbors tub made a study seem worth it. Look through the Backyard tub—all kinds of bird books written by authors who like birds and pays attention to what you can learn out in the yard.”

“This Backyard Neighbors tub reminds me of a display I might see at our favorite bookstore,” Trey added. “You have books about local birds. You put the tray with your nest collection right next to it. The singing robin is next to the nest. You even have a card in here with websites listed. You caught Sarah’s attention with this display. This big tub . . . It just says Birds. . . . I mean, would you go down an aisle at the grocery that just said Food?”

I was learning a lot from these two, so I maximized my time with them. “Is it the books or is it how they are presented?”

“I think if you shared books in smaller tubs and grabbed our attention with labels—maybe even signs—we would know why you thought these were interesting books,” Sarah said. “I mean, it’s okay if some tubs have basic labels like Birds: Reference Books. You know how we have that reference shelf in the school library? We know we can go to reference books to get specific information. But I think your book tubs could help other kids get more curious if they got us excited about our own study. What about new labels? It might help. And make smaller tubs, so someone who doesn’t know much about a subject might not get overwhelmed by the Titanic-sized tub and just walk away.

“Just look at this tub,” Sarah sighed, staring at the Bird tub. “It is too big, and nobody wants to drag out this big collection of bird books. So if we dump the books . . .”

Flump! A huge pile of books now filled the space between the three of us.

“I bet we could find different little collections,” Trey said.

So we unpacked the Bird tub and sorted together, building different stacks of books. The owl pile was quite big. There was a teetering stack of books about birds of prey. A small but colorful pile of hummingbird books begged for a display. The generic stack of bird reference books was now much smaller and less intimidating. One giant tub was transformed into several appealing tubs. Now instead of a giant reference tub and one inviting basket, we had the following:

-

Backyard Neighbors: Our Feathered Friends

-

Lords of the Night: Owls

-

Kings and Queens of the Sky: Birds of Prey

-

Hummingbirds in the Garden

-

Going for a Swim: Water Birds

-

Resources for Bird Studies—a generic collection of resource books that covered a wide range of bird information

To give you an example of the process the kids demonstrated, they pulled out books that concentrated on bird families, eggs, and nests. They focused on the idea of family, and Sarah named the tub Family Reunion Time! This collection was placed with the other bird baskets.

When it was time for them to go to music class, I used part of my planning time to “merchandise” the bird shelf in a new way. I added a few artifacts and added a photo of a cardinal taken by my teaching partner. When the kids returned, I showed Sarah and Trey the new shelf arrangement, and they each gave me an enthusiastic thumbs-up and a big smile. I knew I needed to keep thinking about this situation.

Could I redesign my nonfiction library and make it a place that encouraged browsing? Could the organization and the arrangement and even relabeling of book tubs guide my kids through nonfiction options, encouraging them to browse just like my favorite nursery encouraged me to be captivated by plants, so much that I decided to take some home? Could a makeover encourage more exploration of our classroom library so that I did not need to hold students’ hands and guide them through the shelves like my favorite associate helps me at Lowe’s?

Overnight I pondered what to do, and the next day I asked Sarah and Trey to share the previous day’s library conversation with the class during morning meeting. I wanted them to broadcast how as nonfiction readers, they felt many of our nonfiction tubs and shelves did not attract readers. I encouraged Sarah and Trey to share their honest comments. Heads quietly nodded as they listened to Sarah and Trey’s opinions. Then the two kids explained how they had helped me make over the Bird book tub, and we showed them the new shelf. Some kids looked confused that I was being critical of myself and the room and that I had asked students for help.

“I bet we could all help you with the library,” Trey said quietly but firmly.

More heads nodded. Murmurs traveled through the group. I gazed at my students with blinking eyes and that growing lump in my throat. You know you are listening to a teacher when he or she gets weepy over kids wanting to take ownership of their classroom. My students wanted to help me redesign part of our library. My kids valued books enough to help the team. How lucky am I to work with children every single day? My students teach me so much when I slow down, pay attention, and listen to their messages. I knew that my kids could make our library a better place for our learning community.

And Trey was right. Over the next few days, I organized small groups during workshop to think out loud with me and work alongside me in the library. They knew the goal: given a topic, tub, or shelf, they would rebuild collections and improve the presentation of our books. They could reorganize books into smaller collections and rename those tubs with encouraging labels. Later, students also created companion cards for tubs, adding lists of websites to encourage reading beyond the books in the tubs.

Did the library makeover improve library traffic? Did more kids begin to seek nonfiction books to support their interests? Yes. Some kids still needed me for guidance. It was more natural to go browsing for books with kids now that the library mirrored the kinds of questions and ideas I might pose to a curious reader. Many of the kids, after getting more familiar with our library during the renovation, were more aware of choices, and as a result, they read more nonfiction.

After bus dismissal a few weeks later, I watered plants on high shelves in my room, thinking about the progress we had made as a community. I still have clearly marked book tubs and shelves that help students locate what they need to read and to reshelve books. The change? My organization is no longer driven by dry subject categories and tidy topic labels that helped me categorize books based on generic subjects. I celebrated the library changes that now enriched my students’ reading lives. Because I had talked to kids, listened to their honest opinions, and acted on solutions, my students helped redesign our library. A redesign initiated by students made a difference in our reading lives, and the library now reflects how children learn. Children are complex thinkers that wander and wonder, paying attention to certain elements that may cause them to pause, ask questions, and care about the world. I am glad that my library, the third teacher in the room, can support students and their independent learning.

Here are a few of the collection names created by my students and me:

Animal Collections

Classmates: Our Classroom Pets

Kings and Queens of the Sky: Birds of Prey

Canine Cousins: Wild Dogs of the World

African Journeys: Animals on Safari

Habitat Studies

Life in the Ocean

Jump into the River! Dive into the Pond!

Out in the Garden

Underground Worlds

Earth and Space

Touring the Solar System

If I Was a Rock

Extreme Weather Alert!

Weather: Whys and Wonders

Biographies

Men Who Changed the World

Quiet Women Seldom Make History

Animals That Changed Our World

Write Your Bucket List: Famous Places

Nonfiction Author Collections

Look Through My Camera . . . The Views of Nic Bishop

Where Art Meets Science: The Creativity of Steve Jenkins

Seymour Simon’s World

Sandra Markle: Stories from the Outside

Nicola Davies: Wonderings and Wanderings